Until recently, Sun Zhengcai, the party secretary of the metropolis of Chongqing, "the Chicago on the Yangtze," was seen as a possible successor to Xi Jinping.

Then, in July, the Communist Party of China launched an investigation against him for corruption, leading to Sun's dismissal from office and the precipitous end to his political career.

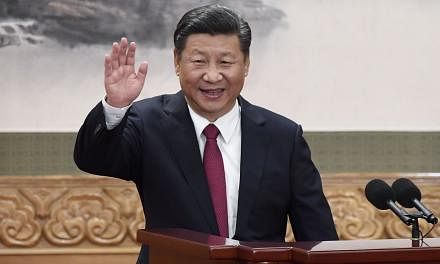

Throughout the Western press, the removal of Sun Zhengcai was treated as conclusive proof that Xi plans to remain in charge after 2022, when term limits and political tradition will require him to give up power.

This has been a common trope in the hazy world of Chinese political analysis since at least 2015, when Foreign Policy published "Xi Jinping Forever," arguing that the Chinese leader would try to extend his rule beyond two terms.

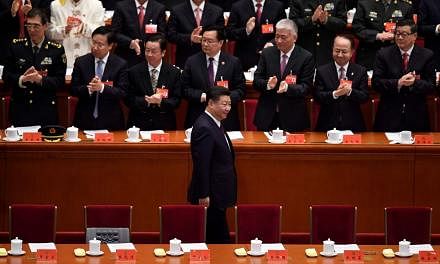

A constant stream of articles, especially in the run-up to this week's 19th National Congress of the Communist Party, has reinforced the consensus that Xi Jinping isn't going anywhere anytime soon.

But Xi's ambitions have been vastly misunderstood, and Sun's dismissal is a critical case in point. Xi used Sun's removal not to aggrandise himself, but rather to quietly designate, in violation of recent tradition, his own desired successor for 2022 - someone whom, for at least the past five years, Xi has managed to groom to carry forward his legacy without attracting too much attention.

Xi has more than half a dozen allies in positions of power throughout China's provinces - like Li Qiang, the Mongolian Bayanqolu, or Li Xi - any one of whom could have been named as Sun's successor in Chongqing. But Xi's choice was striking: He promoted his ally Chen Min'er, who was born in 1960.

Why is his year of birth so important?

Because, based on the traditional retirement age of 68, Chen Min'er - unlike Xi's other prominent allies, who are older - will be able to serve out a double term from 2022, when he will be 62. Were he born even just a year earlier, in 1959, this would have been impossible, as he would have been forced to retire in 2027.

In choosing Chen Min'er as the new leader of the metropolis of Chongqing, Xi has sent a broad hint to both the party and the outside world. The Communist Party doesn't hold press conferences to announce successors; it uses signals like this - even if few in the West seem to be able to understand them.

Xi's privileged treatment of Chen is consistent with their relationship since the early 2000s, when they met in the province of Zhejiang, where Xi was serving as provincial party chief. Chen was the head of the provincial propaganda department, in charge of spreading Xi's message throughout Zhejiang. In this position, he helped write Xi's weekly column in the provincial party newspaper for almost four years.

Xi left Zhejiang in March 2007, when he was moved to Shanghai, only seven months before the 17th Party Congress. Shanghai needed a new party chief, because the old one was removed after being investigated for corruption.

In promoting Xi to Shanghai, one of China's largest cities, the party leadership indicated that he was destined for higher office. Indeed, at the 17th Party Congress in October, Xi entered the Politburo Standing Committee, the party's apex of power, and in March 2008 he was named vice president of China - the definitive sign that he was being groomed to take over in 2012.

Meanwhile, Chen Min'er remained behind in Zhejiang, being named vice governor and then becoming an alternate member of the party's Central Committee at the 2007 Party Congress. He remained vice governor until 2012, the year when Xi was going to become the party's leader. In January 2012, Chen was promoted to the position of deputy party chief of the province of Guizhou.

At the 2012 Party Congress, where Xi was named general secretary of the party, Chen was promoted as one of the 205 full members of the Central Committee and later appointed governor of Guizhou.

Now in charge of the party, Xi announced the start of an anti-corruption campaign whose intensity surprised every observer.

In 2015, the anti-corruption campaign targeted a sitting provincial party chief for the first time: Zhou Benshun, the top official in Hebei. Out of more than two dozen provincial party secretaries, Zhou's replacement was the party secretary of Guizhou, who left his seat to head to Hebei.

Thus Chen was promoted from governor to party secretary - a higher-ranking position - in Guizhou, where he would remain in charge for two more years. This was the first, but not the last time Chen would benefit from the anti-corruption campaign.

Chen's five-year stint in Guizhou coincided with an acceleration of China's fight against extreme poverty. Guizhou is one of China's poorest provinces but has a good track record of producing leaders. Hu Jintao, Xi's predecessor, was Guizhou's party chief in the 1980s. There, Chen was tasked with tackling one of Xi Jinping's most important objectives: the eradication of extreme poverty by 2020. In the process, he made some resounding moves, like convincing Apple to build a data centre in Guizhou.

Under Chen's leadership in 2016, Guizhou reported the third-fastest growth among Chinese provinces, with a claimed GDP growth rate of 10.5 percent.

In return, Xi has repeatedly signalled his trust in Chen. This year, every province has chosen its delegates to the 19th Party Congress. Chinese leaders are themselves delegates at the Party Congress.

Xi Jinping, for example, was a delegate from Shanghai in both 2007 and 2012. For 10 years he has been living in Beijing, where he was also born. Through his career, he also served in Hebei, Fujian, and Zhejiang. Yet, in April 2017, it was announced with great fanfare in the Chinese press that Xi Jinping would be a delegate from Guizhou. Xi's only link to this province is, of course, Chen Min'er. His election was a clear message to party members and the party leadership that Xi trusts Chen.

This trust was reinforced only three months later, in July, when Sun Zhengcai was removed from his post in Chongqing, being put under investigation for corruption. It was an earth-shattering event, as Sun was one of two possible successors for Xi. Sun was also the first sitting Politburo member put under investigation during Xi's term.

Until this moment, the anti-corruption campaign had only hunted wounded or retired top officials, instead of the real political heavyweights of the Politburo or the Politburo Standing Committee. (Bo Xilai, the most significant potential rival of Xi's, fell before the campaign began, thanks to the strange events in the ever-significant town of Chongqing.)

Who benefited from Sun's investigation? Chen Min'er, who was promoted to party chief of Chongqing three months before the 19th Congress, just as Xi was promoted to party chief of Shanghai seven months ahead of the 17th Congress. We could call this the 2007 Shanghai playbook, and it was put into action again.

There is now a lot of discussion in the West about the Party Congress: Will Wang Qishan remain on the Politburo Standing Committee, despite the fact that he is supposed to retire, being above the 68-year age limit? Will Xi revive the post of party chairman? Will he have his name enshrined in the party's constitution, like Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping? Will Xi avoid naming a successor?

But very few observers are talking about Chen and his bright prospects. The exaggerations about Xi's power have obscured the most important question we should be asking: Will Xi manage to install Chen as his successor?

Over the past three decades since Deng Xiaoping retired, Chinese leaders haven't been able to name their own successor. Jiang Zemin had to accept Hu Jintao and fought to keep his own influence alive in the 2000s as a result.

Hu Jintao couldn't install Li Keqiang as his successor and had to accept Xi Jinping. Now, in a sign of his own strength compared to his predecessors, Xi has purged one heir apparent, replacing him with his chosen ally.

Only two possible successors remain: Chen Min'er or Hu Chunhua, Hu Jintao's ally.

In normal circumstances, Xi would have been forced to accept Hu Chunhua, who is the provincial party chief of Guangdong. But his plan seems to be to install Chen as China's next president - in a way that makes it clear he's beholden to Xi, and which allows Xi to maintain his influence.

Over the past three years, instead of analyzing Chen's ascent and his prospects, all the attention has been focused on the idea that Xi aims to remain in power after 2022, based on anonymous sources.

There are two explanations for these rumours: either it is just speculation and worry on the part of party members who later talked to Western journalists, or the rumours were deliberately planted. If so, they could have been planted by Xi's enemies, as a smear campaign to accuse him of wanting to become a dictator. Or the rumours could have been started by his allies, to strengthen Xi's hand in internal party negotiations.

If it were the second explanation, the campaign has failed, as Xi will probably get his way. But if starting the rumours was Xi's strategy all along, it was a brilliant plan: Everybody worried that Xi might rule beyond 2022, while he carefully groomed Chen Min'er.

Unlike Hu Chunhua or Sun Zhengcai, Chen hasn't been a member of the 25-person Politburo, so his chances to become China's next leader were slimmer. But now, when Xi negotiates with party leaders and proposes Chen as his successor, they may be inclined to say yes, keen to avoid Xi's hypothetical third term. And so, Xi might do something no Chinese leader since Deng has achieved: designate his own successor and maintain his own influence from behind the scene once he retires.

When the members of the next Politburo Standing Committee step on stage next week, the real question is who will appear first: Chen Min'er or Hu Chunhua. If it is Hu, then it is the clearest sign that Xi's power has been exaggerated.

But, if it is Chen, as all the signs indicate, then Xi's plan over the past five years has indeed worked. And nobody should be surprised when Chen Min'er emerges as Xi's successor - even if he ends up continuing Xi's agenda and shielding his legacy.

Andrei Lungu is president of The Romanian Institute for the Study of the Asia-Pacific (RISAP). This analysis has been published in the Washington Post and Foreign Policy.