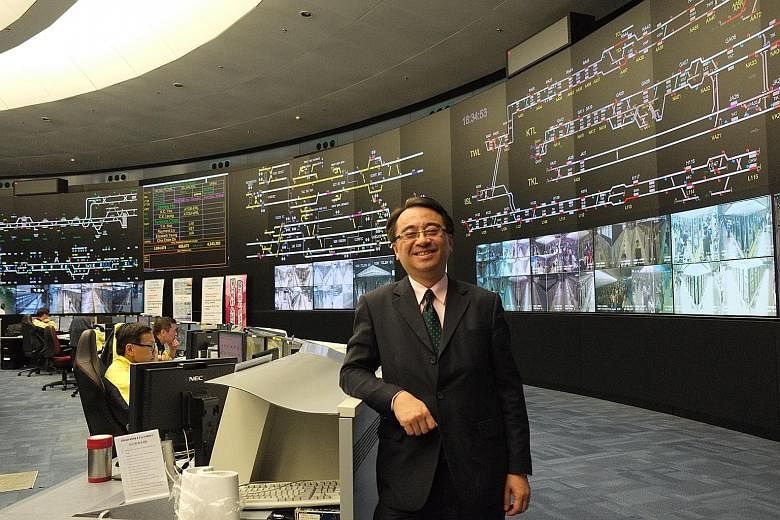

Like a panoramic painting, Hong Kong's entire mass transit railway (MTR) network is represented electronically across a sprawling wall.

Red dots move along various lines, showing where its trains are at that moment. Panels beam scenes of commuters streaming in and out at stations. A clock suddenly lights up with red digits. There is a delay on one of the tracks. The 30 or so "traffic controllers" in the room stop work on their computers and watch. It ticks off - 15, 16, 17. By the 20th second, it fades to black. The train is moving again. Everyone relaxes.

The situation last Monday afternoon sorted itself out quickly. But here at the Super Operations Control Centre (OCC), the central nervous system of the MTR network, no one takes chances.

-

MTR v MRT

-

Here is how Hong Kong and Singapore's rail networks stack up against each other. Hong Kong has one rail operator, MTRC, while Singapore has two.

SMRT runs the North-South, East-West and Circle lines, and SBS Transit runs the North East and Downtown lines.

MTR

Total route length: 221km

Domestic passenger trips a year: 1.55 billion

Fare revenue: HK$11.3 billion

No. of major delays over 30 min: 5 (January to June 2015), 12 (2014), 4 (2013), and 8 (2012)

Distance travelled before delay of over 5 min: 300,000km

On-time rate (within 5 min of schedule): 99.9 per cent

Amount spent on maintenance, renewals and service improvements: over HK$6 billion (S$1 billion, 37 per cent of revenue)

SMRT

Total route length: 129.8km

Passenger trips a year: 730.6 million

Fare revenue: $644.2 million

No. of major delays over 30 min: 7 (2014), 5 (2013), 6 (2012) and 10 (2011)

Distance travelled before delay of over 5 min: 137,000km

Train arrival punctuality (within 2 min of schedule, at least 96 per cent weekly): 87.5 per cent for North-South and East-West lines (affected by speed restrictions due to sleeper replacement works)

Amount spent on repair and maintenance: $121.9 million (18.6 per cent of revenue)

SBS Transit

Total route length: 24km

Passenger trips a year: 575,000

No. of major delays over 30 min: 5 (2014), 3 (2013), 2 (2012), 1 (2011)

• Footnote: Figures for MTR and SBS are for 2014, while those for SMRT are for its FY 2015

Sources: MTRC, SMRT 2015 annual report, SBS 2014 annual report, LTA

Completed two years ago, the OCC is crucial for coordinating speedy responses when crises erupt, says Dr Jacob Kam, MTR Corporation's (MTRC) director of operations. For instance, incoming traffic from other lines will be held at bay and interchange stations alerted. If needed, coaches are activated to bus stranded commuters.

Last year was a busy one for the OCC. There were 12 "major disruptions", the highest since comparative data was collected in 2012. These are defined as delays lasting more than 30 minutes and within the control of the MTR (this excludes weather or passenger factors). Still, Hong Kong's rail system remains one of the most reliable in the world - "the best in class", as Singapore Transport Minister Khaw Boon Wan put it in his blog three weeks ago when exhorting local operators to "close the gap".

Last year, the MTR experienced 273 delays of eight minutes or more, out of a total of 1.9 billion trips. It has an "on-time" rate of 99.9 per cent, which means that only in one out of 1,000 trips do passengers experience a delay of at least five minutes. This is benchmarked against a demanding schedule. Trains arrive every two minutes during peak hours, and three to six minutes at other times.

So what accounts for the purring performance of the network first built 36 years ago, ahead of Singapore's by nine years?

In his blog, Mr Khaw spoke of a "consensus view" - that Singapore has "underinvested in rail maintenance, and our engineering capabilities in this area are still lacking".

This may be true. The MTRC spent over HK$6 billion (S$1 billion) - 37 per cent of its rail revenue - last year on maintenance, renewals and service improvements. Half goes to daily cleaning and inspection works; the other half to capital expenditure, such as replacing the train door guides to prevent foreign objects from jamming there.

By contrast, SMRT spent $121.9 million on repairs and maintenance - 19 per cent of its rail revenue. The operator did not respond to queries on what this covers. It excludes maintenance spending by the Land Transport Authority.

But interviews with Dr Kam and transport experts in Hong Kong and Singapore suggest that there are also broader factors at play, which ensure that incentives are aligned. One is the industry model. The MTRC designs, builds, operates and maintains the entire system here. This is unlike Singapore, where the state pays for and owns infrastructural assets.

In Hong Kong, being in charge of the whole hog helps prevent a culture of silos and results in holistic planning, including in pre-emptive maintenance. The MTRC, in fact, plans 50 years ahead, looking at likely needs in the coming decades, says Dr Kam. "For example, if we know that we have to refurbish the trains in 10 years, we will start looking at the issue now, testing different types of designs."

However, the most important factor is the MTRC's corporate set-up and culture. Dr Kam speaks proudly of a "continuously improving ethos" - to "become better than today". But what underpins this? It is not just a sense of social responsibility. MTRC is not just a public transport operator but also a profitable public-listed conglomerate.

Rather counter-intuitively, it dabbles in a wide range of non-rail businesses - from developing malls to monetising its Octopus card for uses as varied as security access at condominiums.

Though the government is the major shareholder, owning 76 per cent of it, the management is given a free hand to run the show, says Dr Hung Wing Tat of Hong Kong Polytechnic University.

In fact, MTRC is so adept at making money, it was able to turn a government penalty - if there are any major delays, it has to set aside funds to compensate passengers - into a promotional discount that nudges people to take more trips.

One might assume that all this money-making fervour distracts the MTRC from its less profitable rail operations. This, in fact, has been a key criticism of the SMRT, when it was accused of paying too much attention to its retail business.

But it is a virtuous circle in the MTRC. The rail-plus-property model - the government grants it lucrative land development rights above and around train stations in return for building new lines - means it is incentivised to keep rail standards and ridership numbers up, in order to make money off its property.

So, on the one hand, the MTRC is willing to build ahead of demand, as the development that springs up around the stations makes it worth its while. Most crucially, it also understands that it needs to spend in order to make money.

Besides the annual HK$6 billion maintenance budget, it also invests in major outlays, such as HK$6 billion on 93 new trains to replace first-generation trains, and HK$3.3 billion to change the signalling systems.

On how it resists pressures from shareholders to keep expenditures low, Dr Kam wryly says: "Yes, they are also confused. They ask for higher dividends - and lower fares."

But, he adds: "We don't know how to stop, to want to keep doing better... If there is a problem, we don't want it to happen more than once."

So, for instance, among the 12 major delays it experienced last year, four were caused by faulty insulators for overhead lines. The MTRC reacted by putting in place a new quality assurance process for all future procurement.

"It is costly but, in the long run, it is better this way," says Dr Kam.

For all the bouquets, the MTRC has its challenges. Its network is running at capacity because of a higher than projected growth in ridership, acknowledges Dr Kam. This means that there are bottlenecks until new lines are up and running in five years.

Project delays and budget overruns - which forced out its former chief executive earlier this year - exacerbate the problem. Dr William Lam of PolyU attributes these to "political pressures" - legislators holding up the funding.

Among patrons, there is simmering unhappiness over fare hikes. Most recent was a debacle over its ban on oversized musical instruments on trains.

If there is one thing Singapore has going for it, it would be the overwhelming political will to resolve its rail woes.

So how will it learn from Hong Kong? The SMRT did not respond to questions on this. But what is clear is that any solutions adopted cannot be piecemeal, but must look at the big picture of what makes the MTR work.