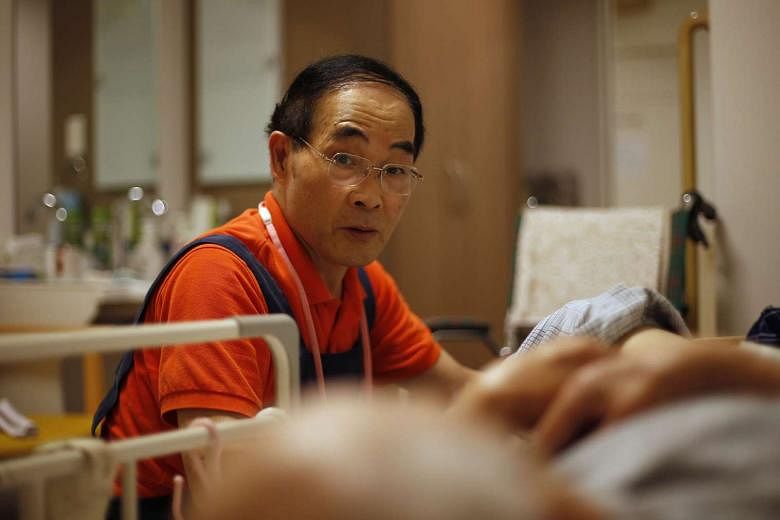

TOKYO • Mr Hiroshi Suzuki had a fulfilling career in which he travelled the world as an engineer. Then, at age 65, he retired. That did not last long. For the past seven years, Mr Suzuki, 72, has been a nursing aide in the Tokyo area, and says he is years away from true retirement.

Economists say if Japan wants to alleviate its worsening labour shortage, it needs a whole lot more people like Mr Suzuki, who is atypical for working into his 70s. Though it has the world's oldest population, the country does an inadequate job of employing healthy seniors, they say.

The reasons: Company policies, work culture and a history of rigid seniority rules that work against older employees, providing a cautionary tale to ageing economies including those in Europe and the United States.

"People in their 70s can still work. There are still so many things you can do as long as you are healthy," said Mr Suzuki, who was a designer and engineer for an electric-furnace manufacturer and now works at a nursing home run by Care 21, one of the few Japanese companies that have abolished a mandatory retirement age.

"There's no need to think about retiring until you turn 80," he added.

Numbering more than 33 million, people aged 65 and older represent more than a quarter of Japan's population. With the world's longest life expectancy - by 2050, women in Japan on average will live past 90 - and a low birth rate, the working-age population is shrinking.

Japan's demographic reality is so extreme that even though it has the highest proportion of working seniors among developed countries, according to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, it is not nearly enough to stem the labour shortage. The number of workers older than 65 rose to 7.3 million last year, or 21.7 per cent of the population for that age group, according to data from the statistics bureau.

The number of workers in Japan is projected to decline to 56 million in 2030 from 64 million in 2014. This forecast by the Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training, a government-related group, is based on conditions that the economy and the labour force participation rate will not change. To avoid such a shortage, the country needs to come up with more innovative policies to pull seniors into the workforce.

Yet Japan's corporate structure is still stacked against widespread employment of older workers. Though some companies have introduced merit-based pay, moving away from a seniority system, age remains an important factor and the career ladder ends for many employees at 60 or before. Mandatory retirement is still in effect in many companies, though there is no official retirement age in Japan.

Mr Taira Yoda, 64, president of Care 21, a nursing service provider, said the company abolished mandatory retirement because it is in an industry with a significant labour shortage, and it wants to give employees the option to earn stable income when they are older.

"(Senior workers) have the capacity to do more," Mr Yoda said. "If Japanese companies can do it, their know-how can be applied to other nations facing ageing populations."

BLOOMBERG