-

40%

Growth rate that China's sharing sector is expected to maintain for the next few years, according to the State Information Centre.

100m

Number of jobs that China's sharing sector is projected to provide by 2020, of which 20 million can be considered full-time employment.

WORLD FOCUS

China's soaring sharing economy

Billions are being invested and millions use the services, but laws need to be updated

Like many Chinese today, Shandong native Zhang Feng, 31, is a Beipiao, or Beijing drifter: someone who has moved to the capital, mostly for work.

His long hours mean he often orders takeouts, even as he yearns for healthy, home-cooked food.

Mr Zhang, a counsellor in the healthcare field, found a happy solution when he discovered Home Cook, an app that offers takeout food freshly prepared at home, often by stay-at-home mums or retirees.

Through the platform, he found Ms Chen Li, 32, a media entrepreneur who lives less than a kilometre away from his home in Changping in the Beijing suburbs, and who is adept at whipping up Sichuanese dishes such as fish stew with pickled greens and three-cup chicken.

"I found her food tasty and we got to chatting, and discovered that we both love running," he said. "Today we are friends, and we have even run a marathon together."

Home Cook is part of China's burgeoning sharing economy, whose underlying idea is that sharing access to commodities is more efficient than owning them.

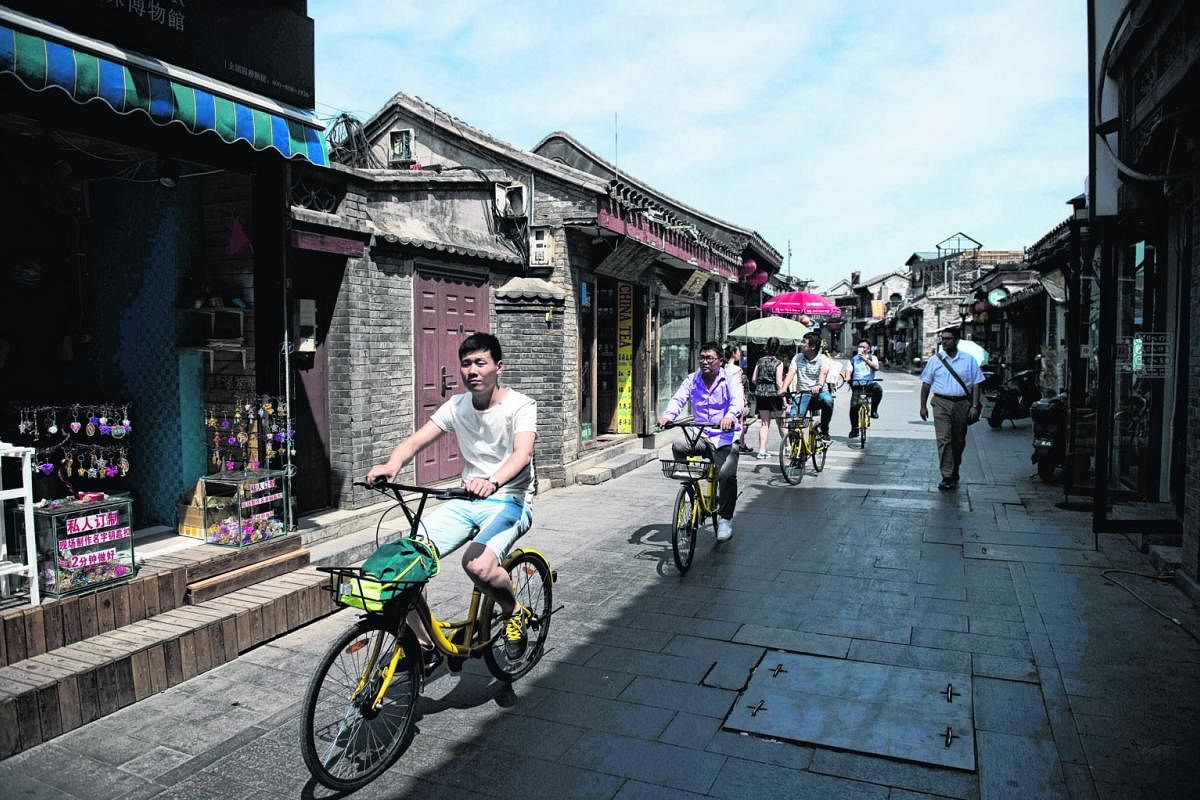

The country that gave the world GPS-enabled bicycles that can be rented and returned anywhere, and whose home-grown ride-hailing firm Didi Chuxing handily defeated Uber, is now racing to "share" all kinds of goods and services, enabled by widespread smartphone use and mature mobile payment systems.

Home-grown firms are now offering to "share" everything from cars and mobile-phone power banks to umbrellas and even basketballs, with investors pouring eye-popping sums into these new start-ups.

Some 171 billion yuan (S$34.5 billion) was invested in the sharing sector last year, said Mr Zhang Xinhong, director of the Sharing Economy Research Institute.

China's sharing economy market is already the world's largest, with a turnover last year of 3.45 trillion yuan, according to a report by the State Information Centre.

It estimated that, to date, close to half of China's 1.4 billion population have used online sharing services at least once, with the sector expected to maintain a 40 per cent growth rate for the next few years.

By 2020, the sector is projected to form one-tenth of China's gross domestic product and provide 100 million jobs, of which 20 million can be considered full-time employment.

Mobike and Ofo, China's two largest bike-sharing firms, are each valued at more than US$1 billion (S$1.36 billion). Both entered the Singapore market earlier this year.

Experts said the amount of money flowing in means it is possible that China's sharing economy is beginning to bubble, and they question if there is actual demand for some of these new platforms.

"Young people are embracing renting as a way of life instead of possessing things," Innoangel fund investment director Emma Zhu, who has held off investing in any of these start-ups, told Reuters. "But the sharing model won't work in every situation. In some cases, they are trying to meet genuine demand, while in others they are not."

Whether the sharing economy can realise its full potential depends on how quickly governments update laws so they cover these new business models without stifling their growth, said Mr Murat Sonmez, a World Economic Forum expert on the fourth industrial revolution - which refers to how the acceleration and convergence of technologies will impact work.

"If you are not employed full time, how much do you pay in taxes, and what happens to social security systems?" he asked. "For many countries, policymaking still lags behind technology's disruption."

BLUEPRINT FOR THE FUTURE

The platforms that work, though, show how the sharing economy can optimise the use of spare capacity, provide a steady source of income and even bring a community closer.

Take Ms Chen, the home chef. The Sichuan native started her own "stall" on Home Cook in late 2014 because her own media start-up was then not doing well.

"I have always considered myself a good cook, and I felt that on Home Cook I could turn my downtime into an income source," she said.

To her surprise, Ms Chen's fiery dishes began to draw a loyal and growing group of customers, such that she had to ask her mother to help. Today, she earns up to 10,000 yuan a month, sometimes meeting as many as 30 orders a day.

But what keeps her going besides the income is the community that has sprung up around her kitchen.

Chefs on the platform serve customers within a 3km radius, and like many successful home chefs, Ms Chen has started a WeChat group for her regular customers.

Her group is 260-strong today and is now something of a neighbourhood support network, with members sharing about their day and getting help from one another.

"When my dad suffered a sudden heart attack in March and had to be transferred to a more specialised hospital, they were the ones who reached out to their doctor friends and helped me get different medical opinions based on the diagnosis," Ms Chen recalled.

One diner even drove to the hospital to assist with the transfer when she could not secure an ambulance.

"It was very gratifying, these were just strangers that I had cooked for, but now they have become friends I can depend on."

ADDRESSING TRUST, LEGAL ISSUES

While Home Cook boasts 23,000 home chefs and two million registered users, the firm said one of its most enduring challenges is to ensure food safety.

Indeed, many start-ups are still trying to see how to make the sharing economy work, as are governments.

All Home Cook chefs undergo a course on kitchen sanitation and food hygiene, and may be subject to surprise checks. Each order is also insured against any food poisoning incidents, said Mr Ma Xiaolong, Home Cook's head of chef management.

But the firm still operates in a legal grey area as China's laws have not kept up with the sector's innovations. For instance, applications by home kitchen operators for food business licences are mostly rejected as they are held to the standard of commercial restaurants.

However, things are changing. This month, Shanghai started a pilot scheme to manage and license small food and beverage operators, effectively legalising them for the first time. This is in line with Beijing's directive last month to boost support for sharing-economy firms.

Earlier this month, China's top economic planner issued new guidelines aimed largely at removing barriers to markets for new sharing businesses. Premier Li Keqiang is also a keen supporter, describing sharing firms as "a reinvigorating force" in China's economy.

The support of the central government may explain the optimism permeating China's sharing economy.

Home Cook, for example, is expanding into its seventh city, Changsha, capital of central Hunan province, later this year.

"We saw with Didi and the bike-share companies that the government is actually quite open- minded in how it deals with novel sharing-economy businesses," said Mr Ma.

"And new laws, such as the one for food safety that Shanghai just introduced, show that city governments are also starting to take a more enlightened approach towards unconventional ideas."

Join ST's Telegram channel and get the latest breaking news delivered to you.

A version of this article appeared in the print edition of The Straits Times on July 25, 2017, with the headline China's soaring sharing economy. Subscribe