BEIJING (CHINA DAILY/ASIA NEWS NETWORK) - As China's anti-graft campaign approaches its third year, behind-the-scenes efforts are being made to educate officials and dissuade them from accepting bribes or succumbing to other forms of graft.

In the past two years, China's crackdown on corruption has made headlines across the world as disgraced former officials have been hauled before the courts.

So far, the campaign has netted more than 50 high-level officials, including Zhou Yongkang, a former member of the Standing Committee of the Political Bureau of the Communist Party Central Committee, and thousands of lower-level cadres.

But away from the glare of the media spotlight, strenuous efforts are being made to educate officials about the serious consequences of corrupt practices and prevent them from falling into the trap in the first place.

At the Guangdong Anti-Corruption Education Centre in Guangzhou, the message is spelled out clear and simple. In the marble lobby a Communist Party flag, bearing a hammer and sickle and as big as half a badminton court, flies next to a crystal droplight that represents the Sword of Damocles, a symbol of the conflicting pressures facing those in positions of power.

The centre's anti-graft exhibition features a reconstruction of a prison guardhouse: looking through the barred windows, one can see life-sized cardboard cutouts of three disgraced former officials standing dejectedly in a 2 sq m cell, the walls behind them covered with scratched tally marks and pieces of doggerel. One message reads: "Painful days. Never come here."

The guardhouse, including the messages scratched on the walls, is an exact replica of a real building in Guangzhou, according to Ms Xue Mei, the head of the centre: "It's used to warn officials. To make them fully aware of the serious consequences they face if they do something they shouldn't."

The centre has also reproduced a scene of a former city security bureau chief hiding his ill-gotten gains in a 1m-high safe box set inside a double wall in his parents' isolated farmhouse. Above the safe box, a large flatscreen television plays a looped video of the man, who was arrested in 2008 on charges of accepting bribes worth more than 18 million yuan (S$3.8 million), crying and confessing his crimes.

"I am so full of remorse," the former official, wearing an orange prison uniform, said with a sob. "I have embarrassed my family and my ancestors."

Nationwide effort

Anti-graft, or clean government education bases have opened across the country, and are playing a major role in making officials think twice about graft.

Since it opened in April 2013, the Guangdong Anti-Corruption Education Centre has received more than 100,000 visitors, including about 600 departmental-level officials. This year, the monthly visitor numbers have risen from 3,811 in March to 7,660 in April, and more than 10,000 in September.

There are more than 200 similar centres, of varying size and scale, throughout Guangdong province. Meanwhile, Xiamen, a coastal city in Fujian province with a population of 3.7 million, has 52. Hebei province has 28 provincial-level centres, and Hubei province opened its first village-level anti-graft education centre last year.

Centres for training officials at city level and above are usually located near prisons that house corrupt officials. The juxtaposition is intended as a warning, of course, but also it's convenient for transporting convicted former officials to speak to cadres visiting the centres.

According to Ms Xue, the Guangdong centre has hosted more than 10 speakers, including a former mayor who was sentenced to 11 years' jail for accepting bribes.

"The first thing she said was, 'I used to sit where you are sitting, listening to other people making speeches, but now I am on the stage'," Ms Xue said. "She was in tears, and so were the audience, many of whom were her former colleagues. They recognised her, and waved when she walked into the room."

Ms Xue said the prisoners only address officials in positions considered to be at high risk of corruption, but tours of the prisons where corrupt cadres are held are also a part of the program for higher-level officials.

Mr Guo Jin, head of the Beijing anti-graft education centre, said: "We frighten officials away from corruption by showing them the cost of accepting bribes."

Founded in 2006, the Beijing education centre, one of China's first anti-graft centres, has received more than 320,000 visitors, according to Mr Guo.

In a video shown to visitors before they enter the exhibition hall, a heavy steel door slams shut, its hinges squealing, and then prisoners are seen exercising in blue uniforms behind barbed wire as a harsh wind scatters fallen leaves.

"I put the video on a large screen and turn the volume up to maximum," Mr Guo said. "The effect has to be striking to make the visitors realize that committing a crime brings serious consequences."

The exhibition compares the lives of dozens of corrupt officials, showing them before and after they were caught. In one photo, a former district head in Beijing, who took more than 16 million yuan in bribes, is shown drinking red wine at a luxury banquet, but in the next shot he's wearing a prison uniform and sitting on a stool eating steamed bread and vegetable soup with a wooden spoon.

Another exhibit shows contrasting photos of a former official addressing a meeting and assembling cardboard boxes in prison.

A large photo of prison cells is flanked by a TV that plays surveillance video of the prisoners' daily lives: performing menial tasks, such as folding the quilts on their bunk beds, and sweeping up.

High-tech approach

Many of the centres have adopted high-tech display methods to ram their message home. In the Guangdong centre, a movie theatre equipped with a large circular screen and surround-sound audio shows footage of the media coverage of trials of corrupt officials.

As the video ends, the mosaic of TV screens that make up the theatre floor displays a sheet of ice that cracks under the feet of the audience, sending shards into a deep, dark hole. It's a none-too-subtle warning that being an official is like walking on thin ice, and any unlawful act could cause their downfall.

"The exhibition is very educational," Mr Li Yiwei, the Party chief of Foshan city in Guangdong, said during a visit. "Every Communist Party official should pay a visit."

Mr Li Jianguo, the head of a large petrochemical company, was shocked by an exhibition that featured Chen Tonghai, the former head of the China Petrochemical Corp, who was handed a suspended death sentence after being convicted of graft worth almost 200 million yuan.

"He used to come to my office. We even shook hands," Mr Li said, shaken.

At one time, the centre was only open to officials above the level of chu - civil servants of middle standing - but later ting, or section heads, were admitted too, and then ministers.

Now, however, 70 per cent of the visitors are lower-level officials and those outside the civil service but still in positions of authority, such as businessmen and teachers.

Ms Xue said the centre wants to educate more people across a wider scale, and the impact it's made has prompted a number of anti-graft organisations, including the Independent Commission Against Corruption in Hong Kong, to arrange exchange trips.

Getting the message across

A prison stands next to the Beijing Anti-Graft Education Centre, its barbed wire and observation towers clearly visible to visitors entering the centre. Founded in 2006, the anti-graft facility was one of the first in China.

Its exhibition, which has only one topic, the corruption of officials, is updated every two years. "We have very limited space, so we focus on showing the most important part of the message - what happens to corrupt officials," said Mr Guo Jin, the centre's head.

The exhibition relies heavily on a "before and after" motif, depicting the lives of officials prior to conviction for corruption and their subsequent downfall. Footage of people confessing their crimes plays on a loop, while the walls are covered with photos of prisoners. One sections features a luxury watch worth 179,000 yuan given to a corrupt official, alongside photos of the same man behind bars after being sentenced to 10 years' jail.

The character yu, or "desire", has been hollowed through one of the walls, and looking through it, one sees a full-sized photo of a prison cell.

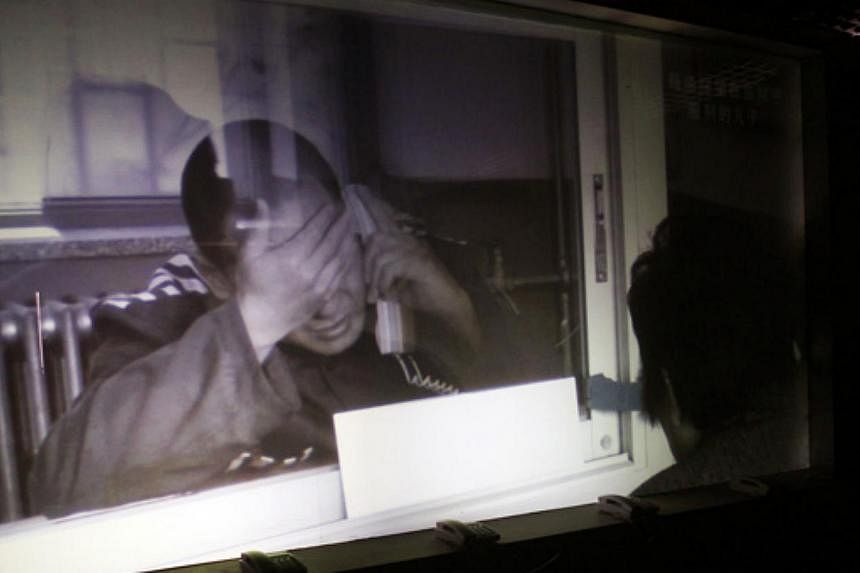

In a mock-up of a visiting room, where prisoners and their families are separated by a glass wall and converse via telephones, audio of a genuine conversation between a mother and son plays whenever a visitor enters the room.

"I miss you, son, but I'm afraid I won't live long enough to see you released," the mother says, while in the background one can clearly hear the convicted man sobbing softly.

Distorted perceptions

A relief sculpture on the gates of the Guangdong Anti-Graft Education Centre depicts the Xie Zhi, a single-horned beast from Chinese mythology, similar to the Western unicorn, that symbolizes the rule of law. Whenever it encounters injustice, the Xie Zhi charges and bites the guilty party.

After passing through a hall featuring Party flags and a droplight shaped like the Sword of Damocles, visitors enter a first-floor exhibition devoted to the history of the fight against corruption that shows how previous generations of officials lived humble lives. A prime exhibit is a photo of Mao Zedong's shoes, their soles almost worn out.

On the second floor, the exhibition concentrates on individual cases of corrupt officials, whose photos or cutouts are kept behind bars. The dim lighting and replica cells create a spooky atmosphere.

Not schools for scoundrels

In October, an education centre in Huai'an city, Jiangsu province, opened a display about the methods of torture used in imperial China. It shows life-size mock-ups of prisoners being subjected to the infamous Tiger Bend - by which a prisoner's legs are broken slowly and painfully - burning, cutting, flaying, and being stretched on a rack.

This method of "education through warnings" is probably a Chinese invention, and has a long history, according to Mr Du Zhizhou, deputy director of the Centre for Integrity Research and Education at Beihang University, who said the method is one of the most effective forms of anti-graft education because the visiting officials can learn lessons by observing the treatment meted out to former colleagues.

"In 2007, I visited a centre in Beijing, and came away feeling that it does shock visitors to some degree," he said. "But education only works in conjunction with an efficient anti-graft programme and appropriate punishments. The influence education can have on the fight against corruption depends on the soundness of the system, and whether the punishments will deter potential offenders."

Mr Du said education can reduce the urge to act corruptly, while the system reduces the opportunity for such behavior. When the opportunities for corruption are widespread, it's difficult for education to achieve the desired effect.

Although most of the comments in the guest book at the centre in Guangzhou were positive, one anonymous visitor had written: "The tour wasn't just educational. It also prompted a series of questions, such as What's wrong with our Party officials? How were corrupt officials promoted and how did they gain power? Did the government test them? Why didn't the government supervise them? Why didn't the people supervise them?"