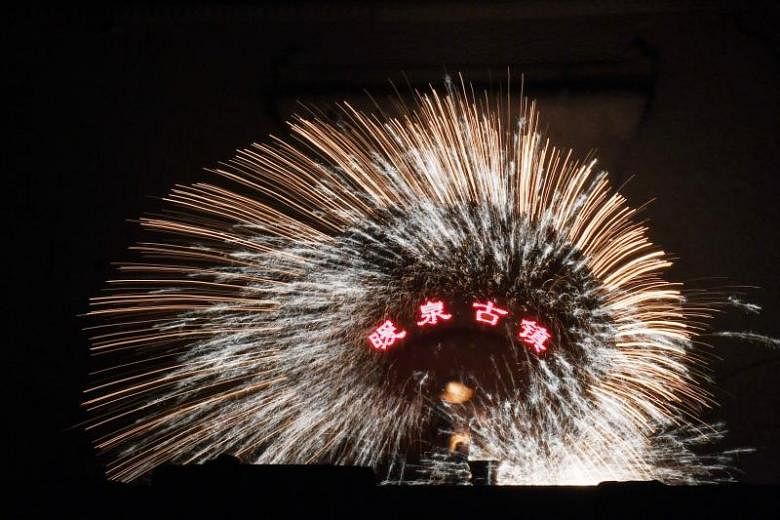

NUANQUAN, CHINA (AFP) - Blacksmith Wang De flings a ladle of molten steel against a cold brick wall, sparking a spectacle of white-hot light in the night sky and keeping alive the flame of a centuries-old Chinese New Year tradition.

Fireworks were invented in China and have been a mainstay of Chinese New Year celebrations, but the remote village of Nuanquan in northern Hebei province has perfected an alternative kind of light show for the past 500 years.

For the performance, known as the Da Shuhua (Beating the Flower Tree), scraps of metal are melted at scorching temperatures and poured into a bucket, where performers like Wang create mesmerising spectacles of light by tossing ladles of the liquid against the wall.

The molten metal - heated to temperatures of up to 1,600 deg C - creates spectacular effects that fill Wang De with pride.

"When you see it, it'll affect you profoundly," the 55-year-old blacksmith, wearing a sheepskin jacket and protective glasses, told AFP.

The three-day show is only put on around Chinese New Year, but is a fast-growing attraction that now draws over a thousand people to each performance.

Its future is not certain, however, as only four blacksmiths remain - and the youngest is 50 years old.

Few people are interested in learning the skills - scars and burns are inevitable - and the younger generation is anyway tending to leave rural China for a better life in the cities.

"It's extremely dangerous and it doesn't make much money," said Wang, who also farms corn to supplement his blacksmith's income.

He has passed on the craft to his son, but he has moved to Shanghai to seek a different career. Still, Wang De is hopeful he will return to keep the flame alive.

"When we no longer can pull this off, people can learn from him. I have this confidence that (Da Shuhua) will be passed on."