Three years after she had an abortion, human resource executive Jin Hongyan is still filled with remorse about the baby girl she could have had. She had hoped to keep the child, but that would have cost her a 30,000 yuan (S$6,600) fine under China's one-child policy - a hefty sum at a time when her family did not have a steady income.

So when the Chinese government announced the abolition of the decades-old policy last Thursday, she was on the verge of tears.

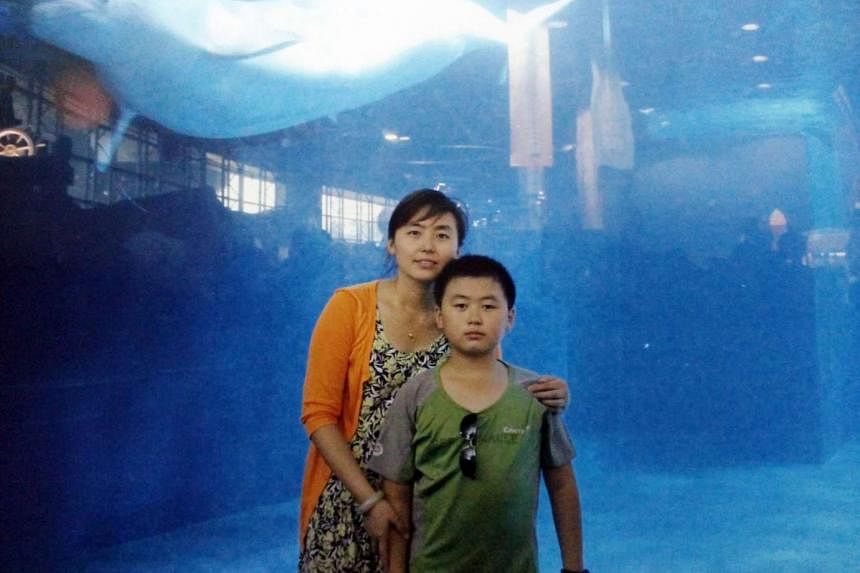

"Why couldn't this policy have come sooner?" lamented the 41-year-old mother of a teenage boy who lives in north-eastern Liaoning. "I carried her for four months. I still think about her."

But while she can now have another child, Ms Jin no longer has any desire to. "My son is against it because he feels the age gap will be too big. Honestly, I don't think I have the energy to have another child either."

Hers was a common sentiment among several Chinese parents whom The Sunday Times interviewed after last Thursday's announcement, which ended the controversial measure introduced in 1979 to help boost economic growth.

-

How policy evolved

-

China's one-child policy was introduced in 1979 as the country began its process of reform and opening up. Its aim was to curb population growth and help boost economic growth.

Official implementation began in 1980, and fines were imposed on those who flouted the rule. The policy proved effective in population control but became controversial due to cases of forced abortion and infanticide.

From the mid- 1980s, the policy was gradually relaxed, with the authorities allowing two children for families in rural areas, or for households where both parents were the only child. In 2013, this was broadened to allow couples to have two children if either parent was an only child.

Last Thursday, amid concerns over its ageing population and gender imbalance, China announced the end of the policy.

All couples here are now allowed to have two children.

The decision, which benefits about 90 million Chinese couples, was one of the most significant outcomes at the end of a four-day, closed-door meeting among top Chinese officials in the capital. The new policy is aimed at rebalancing China's gender ratio and boosting population growth in its ageing society, but experts say its impact may not be as effective as the government hopes.

As the one-child rule had already been gradually relaxed in prior years, the latest news benefits only older parents, most of whom are at least around 35 years old and hence reluctant to have another child.

"If this news came earlier I might have considered. Now it's too late," said Ms Zhu Ying, 42, who works at a state-owned enterprise and has a 16-year-old son. She remembers reluctantly going for an abortion 11 years ago when she became pregnant with a second child.

"Although I've always wanted to have another child, I don't think I have the willpower now," she said. "My son is going to university in a few years and I was preparing to relax a little. I don't want to be tied down by another child."

Age is not the only consideration either. The cost of having a second child is another major concern for many parents, such as Mr Shen Hong, 35, and Ms Zhang Huanli, 33, both of whom work in estate management.

The couple live in Beijing with their 13-year-old son and have a monthly mortgage bill of 5,000 yuan, which takes up close to half of their combined monthly income.

"We both would love another child, but because our parents cannot help to take care of them, I would have to quit my job," Ms Zhang said. "Financially that would make things too difficult for us."

Her response reflects the hesitation many Chinese parents have about having a second child today, particularly in major cities where the cost of living is high.

Only 12 per cent of eligible couples nationwide applied to have a second child when the one-child policy was relaxed in 2013, which allowed couples to have two children if either parent was an only child. In Beijing, the take-up rate was lower, at less than 7 per cent.

Overall, that policy tweak produced only 470,000 more babies in China last year, far below the two million more expected annually. It is possible that the latest relaxation of rules will be met with similar reticence.

In an online survey that drew close to 200,000 respondents on a popular Chinese news website, more than 40 per cent said they would not have another child. A quarter said they would, while the rest were undecided. But for some Chinese, the latest news is a godsend.

For instance, civil servants Zhou Jie, 42, and Deng Xiaen, 43, decided to have a second child after initially grappling with a decision.

"My concern is my age, but I grew up in a happy family with four brothers and sisters and I hope my daughter can have the same joy I had with my siblings," said Ms Deng, who lives in south-western Guangxi, where she feels the cost of living is more affordable.

Beijing housewife Xiang Yuanfang, 37, is also ready to have another child, although she suffered a miscarriage four months ago. "A second child truly completes a family. Children are gifts from heaven."

But the end of the one-child policy does not come into effect immediately. It is set to go through a process of refinement and endorsement before being implemented by provincial-level governments, which can introduce their own variations as well. A top Chinese health official last Friday expressed hope that the policy can be rolled out across most of the country by the first quarter of next year.

Still, parents whom The Sunday Times spoke to greeted the end of the one-child policy with some relief. While they say they understand the government's reasons for implementing the policy, most expressed unhappiness - even resentment - at the official intrusion into their personal lives.

"People were deprived of their basic right to choose how many children to have," said teacher Miao Chunlei, 39, who is looking to have a second child now.

Civil servant Lu Shan, 35, feels the old policy was "completely unreasonable" and has produced unintended consequences, such as pampered children or "little emperors". "It's common to see children these days who are rude, timid or selfish. I shudder to think what will happen when they all grow up."

•Additional reporting by Lina Miao and Carol Feng