Ryuichi Iwasaki was a jobless, short-fused man who spent his days locked away in his room, playing video games and reading about serial murders around the world.

The 51-year-old lived with his aunt and uncle in Kawasaki city just outside Tokyo. The couple, who are in their 80s, had taken him in as a young boy after his parents divorced. Even in his adult years, they continued to give him spending money and prepare his meals. But he hardly spoke to them.

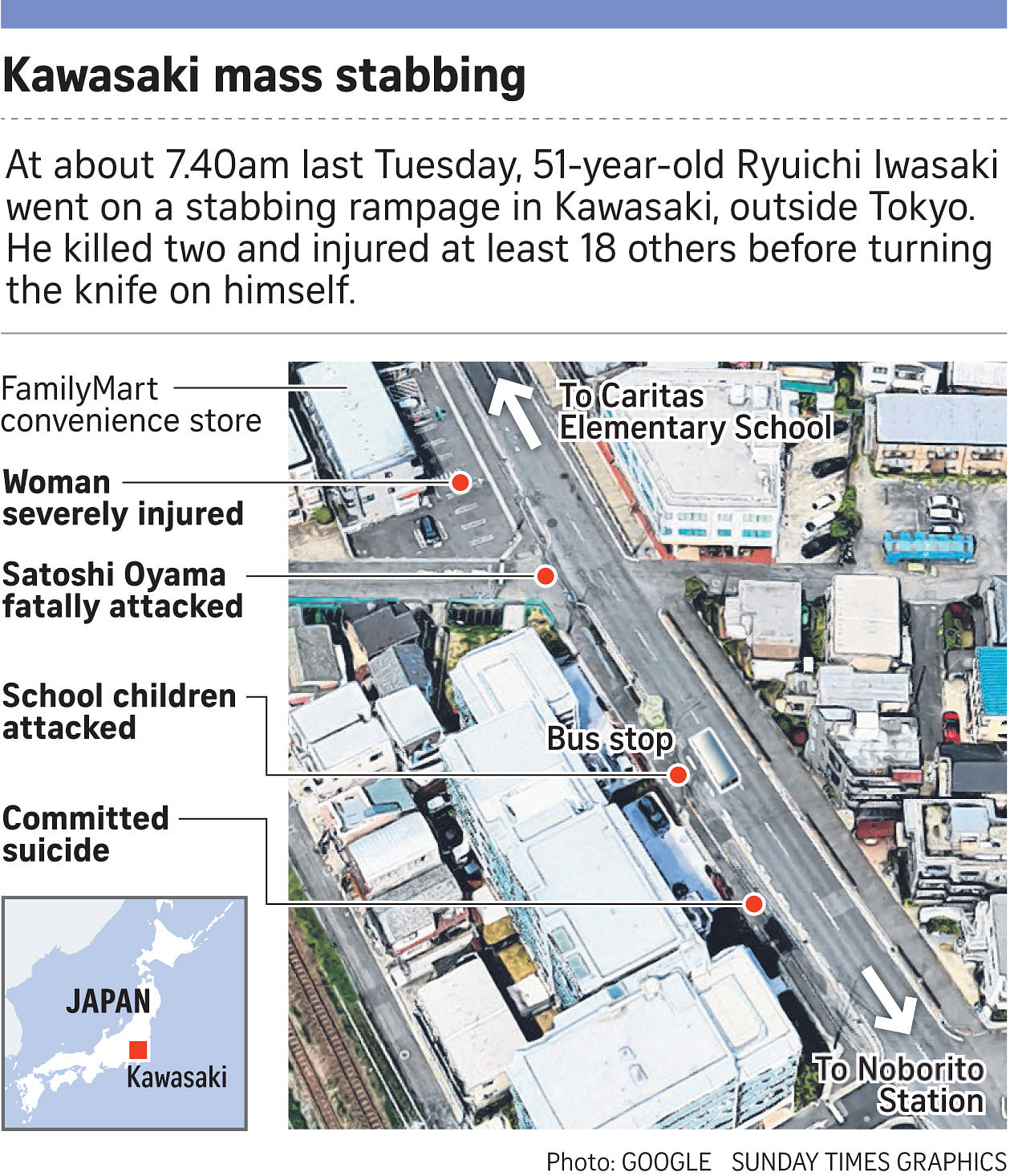

Last Tuesday, Iwasaki, whose childhood dream was to be a zookeeper, went on Japan's worst stabbing spree since 2016, in a 20-second rampage that ended when he took his own life.

Iwasaki left home, chirpily greeting a neighbour "Good morning!" in an interaction that struck her as odd. They had had an altercation last year, when he rang her doorbell at daybreak to yell at her for 30 minutes about a tree branch from her garden that he said grazed his eye.

Little did she know that 40 minutes later, he would kill two people - 11-year-old Hanako Kuribayashi, and 39-year-old Satoshi Oyama - and injure at least 18 others, many of them schoolgirls.

Iwasaki's motives remain unclear, as no suicide note has been found. But accounts from police investigators and city officials paint a picture of a troubled man who became more withdrawn from society as he grew older.

Police believe he did not own a computer or a mobile phone. They took from his room knife boxes, old crime magazines and a notebook that Iwasaki used to keep tallies - though of what, they do not know.

What they do know, however, is that on that fateful Tuesday, after greeting his neighbour, Iwasaki, dressed all in black and carrying a backpack containing four knives, took the local train from Yomiuriland-mae station, which is closest to his home, to Noborito station, three stops away.

He then walked to a convenience store where he put on gloves and armed himself with a 30cm knife in each hand. Then he began his rampage, screaming "I'm going to kill you!" as he aimed primarily for the neck of his victims.

His first victim was a 45-year-old mother, who was severely injured. Then he attacked Mr Oyama, a Foreign Ministry official and father of one of the unharmed schoolgirls.

Running along the road towards Noborito station, Iwasaki saw a line of schoolgirls waiting to board their bus. He struck them one by one from the back of the line, then stabbed himself in the neck when the bus driver, hearing the girls' screams, shouted at him.

-

A history of violent crime

-

Despite having one of the lowest crime rates in the world, Japan has witnessed some shocking crimes. The Sunday Times recounts some of these horrific incidents.

ZAMA SUICIDE PACT KILLINGS

In 2017, police found nine human heads and 240 bones in 27-year-old Takahiro Shiraishi's 13.5-sq m apartment in Zama city, an hour's drive from central Tokyo.

Shiraishi had lured his despondent victims via Twitter, claiming to be a suicide expert who could help them end their lives.

Eight of the nine victims were women, mainly in their late teens to early 20s, while the ninth was the boyfriend of a victim. Shiraishi said his motives were sex and money.

SAGAMIHARA RAMPAGE

In 2016, Satoshi Uematsu, then 26, went on a stabbing rampage at a home for the disabled in Sagamihara, north of Tokyo.

Uematsu, who had worked at the care facility but was sacked for his radical thoughts, said he wanted to "cleanse society of imperfection" and had even written to the Cabinet Office about his Hitler-inspired ideologies.

The attack left 19 dead and 26 others injured in what remains the bloodiest crime in post-war Japan.

AKIHABARA STABBINGS

In 2008, Tomohiro Kato, then 25, killed seven people and injured 10 others in Akihabara, Tokyo's popular electronic goods area, when he rammed his truck into a crowd, before alighting and going on a stabbing spree.

Kato, who was mired in poverty and had been sacked from his temporary job, said he was "lower than trash because at least the trash gets recycled".

OSAKA SCHOOL MASSACRE

In 2001, Mamoru Takuma, then 37, entered Ikeda Elementary School in Osaka and began stabbing pupils and teachers at random with a kitchen knife.

Eight pupils died, while a further 13 children and two teachers were severely wounded.

The case resulted in schools beefing up their security measures. Takuma, a former janitor at another school, was executed in 2004.

Walter Sim

The case sent shock waves throughout Japan, which has one of the world's lowest crime rates.

Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has vowed to look at how to protect school children on their commutes to and from school.

Welfare groups have warned against singling out recluses as this could lead them to withdraw even further into their shells.

Still, there have been attempts to make sense of the senseless attack.

Japanese media reached out to Iwasaki's former teachers and classmates, all of whom described a school boy who did not stand out.

"He and his friends would shove each other playfully, but he didn't attack anyone violently," a teacher told public broadcaster NHK.

A former classmate told the Yomiuri Shimbun: "He was quiet and didn't stand out. I have no memory of him talking with friends."

Neighbours said they knew little about the man. But one housewife in her 70s recalled that he had flown into a rage at her barking dog many years ago and asked her: "How about I kill it for you?"

The case also prompted a bout of soul-searching over whether anything could have been done to pre-empt, or prevent, the attack.

Kawasaki officials do not think so. Mr Tadashi Takeshima, who heads the city's mental health and welfare centre, told a news conference: "There were no signs leading us to suspect he was ill or that he held an inner anger towards society. But since this incident did occur, one issue we will have to deal with is coming up with measures to intervene at an early stage in order to provide support."

Still, Iwasaki's relatives had been concerned over his increasing withdrawal from society. One of them told the welfare centre that Iwasaki "had not worked for a long time and was becoming reclusive".

The centre spoke to his aunt and uncle several times, leading the aunt to leave a note at his door in January to voice her concerns.

He screamed in reply: "I take care of myself. I make my meals and do my washing. This is the lifestyle I have chosen, so how dare you say that I am a social recluse."

Criminologist Enzo Yaksic, who founded the Atypical Homicide Research Group at Northeastern University in Boston, told The Sunday Times: "Iwasaki appeared to be in high spirits before the attack, as he probably interpreted his impending attack as a pleasurable experience."

Mr Yaksic, who is also director of the non-profit Murder Accountability Project, said that like most mass murderers, Iwasaki lacked interpersonal skills and "resorted to abrasiveness to address what most would label petty slights".

And by wielding two knives and attacking young girls, he sought to target the weakest in society to inflict maximum damage.

"Perhaps we might learn that Iwasaki suffered losses in his life that he was unable to surmount and that his reaction to them influenced his actions, specifically his choice of victims," said Mr Yaksic.