BEIJING • Chinese primary and secondary schools are often derided as gruelling, test-driven institutions that churn out students who can recite basic facts but have little capacity for deep reasoning.

A new study, though, suggests that China is producing students with some of the strongest critical thinking skills in the world.

The unexpected finding could recast the debate over whether Chinese schools are doing a better job than US ones, complementing previous studies showing Chinese students outperforming global peers.

But the new study, by researchers at Stanford University, also found that Chinese students lose their advantage in critical thinking in college. That is a sign of trouble inside China's rapidly expanding university system, which the government is betting on to promote growth as the economy weakens.

The study, to be published next year, found that Chinese freshmen in computer science and engineering programmes began college with critical thinking skills about two to three years ahead of their peers in the United States and Russia. Those skills included the ability to identify assumptions, test hypotheses and draw links between variables.

Yet Chinese students showed virtually no improvement in critical thinking after two years of college, even as their US and Russian counterparts made significant strides.

The findings are preliminary, but the weakness in China's higher education system is especially striking because Chinese leaders are pressing universities to train a new generation of highly skilled workers and produce innovations in science and technology to serve as an antidote to slowing economic growth.

The government has built hundreds of universities in recent years to meet soaring demand for higher education, which many families consider a pathway into the growing middle class. Enrolment last year reached 26.2 million students, up from 3.4 million in 1998, with much of the increase in three-year polytechnic programmes.

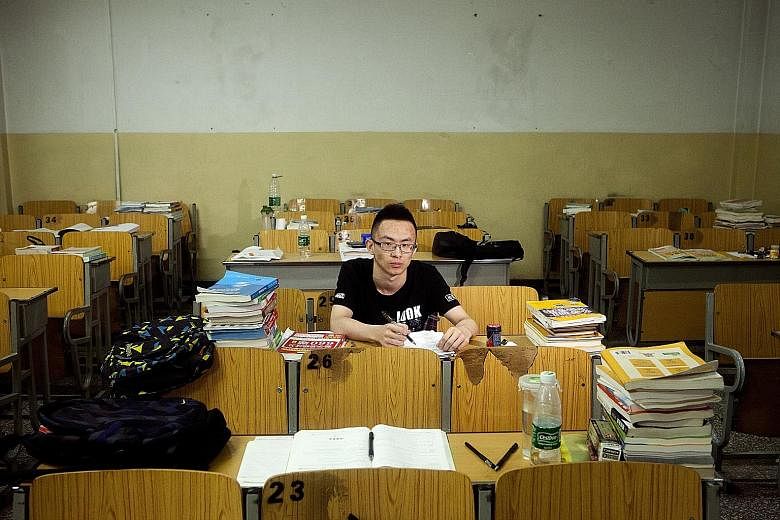

But many universities, mired in bureaucracy and lax academic standards, have struggled. Students say the energetic and demanding teaching they are accustomed to in primary and secondary schools all but disappears when they reach college.

"Teachers don't know how to attract the attention of students," said Mr Wang Chunwei, 22, an electrical engineering student at Tianjin Chengjian University, not far from Beijing. "Listening to their classes is like listening to someone reading out of a book."

Others blame a lack of motivation among students. Chinese children spend years preparing for the gaokao, the all-powerful national exam that determines admission to universities in China. For many, a few points on the test can mean the difference between a good and a bad university, and a life of wealth or poverty.

"It is astounding that China produces students who are much further ahead at the start of college," said Mr Prashant Loyalka, an author of the study. "But they are exhausted by the time they reach college, and they are not incentivised to work hard."

When students reach college, the pressure vanishes.

"You get a degree whether you study or not, so why bother studying?" said 24-year-old Wang Qi, a graduate student in environmental engineering in Beijing.

The Stanford study, based in part on exams given to 2,700 students at 11 mainland universities, has its own limitations. It does not account for people who are not enrolled in universities. It looks exclusively at students in computer science and engineering programmes.

And it does not offer insights into creativity, a topic often hotly debated in discussing the Chinese education system.

The Stanford researchers suspect the poor quality of teaching at many Chinese universities is a key factor. Chinese universities tend to reward professors for achievements in research, not teaching abilities.

Mr Eric Li, a venture capitalist in Shanghai who helped finance the Stanford study, said the success of Chinese secondary schools in teaching critical thinking could mean more innovation among younger Chinese that would help the economy.

"The common narrative that we hear is that the Chinese educational system kills creativity and kills innovation," he said. "But China is probably one of the most entrepreneurial societies in the world."

NEW YORK TIMES