China makes tracks on modern Silk Road

On Sunday, Beijing will host a two-day summit on the Belt and Road Initiative, an ambitious project that incorporates an overland network of highways and railroads as well as a maritime route. This is the first in a series that looks at the mega project spanning China, Central Asia, South-east Asia, South Asia, Africa, the Middle East and Europe.

That China is holding a mega summit in Beijing this coming week to drum up international support for its Belt and Road Initiative is telling. China may have helped to drive global growth for many years now, but the size and ambition of the project is such that Beijing alone cannot make it happen.

So what is the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) or One Belt, One Road as it is better known?

MODERN-DAY SILK ROAD

Chinese President Xi Jinping, in two speeches in the space of about a month in 2013, proposed the revival of the Silk Road, ancient land and sea trade routes that linked China to the rest of Asia, as well as Africa and Europe.

In September that year, in Kazakhstan, he spoke about building a Silk Road Economic Belt, an overland network of highways and railroads linking China through Central Asia to Europe. A month later, in Jakarta, he proposed the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road that links China's sea ports to those in South-east Asia, South Asia, Africa, the Middle East and Europe.

Along these routes would be transport nodes and trading and industrial hubs. Building up these routes would mean beefing up infrastructure such as ports and railways, especially in less developed nations along the routes.

In Jakarta, Mr Xi also proposed the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) to help finance the building of infrastructure in the economies along these trade routes.

Together, the land and sea networks came to be known in Chinese as yidai, yilu, or One Belt, One Road. This was later officially translated as Belt and Road Initiative, but One Belt, One Road is more often used.

In March 2015, the National Development and Reform Commission came up with a blueprint of the BRI that painted a broad vision of its aim - to promote the orderly and free flow of economic factors, efficient allocation of resources and deep integration of markets.

But it is clearly China-centric - it is to enable China to "further expand and deepen its opening up, and to strengthen its mutually beneficial cooperation with countries in Asia, Europe and Africa and the rest of the world", said the blueprint.

It is ambitious in that it encompasses 65 per cent of the world's population, about one-third of the world's gross domestic product and about a quarter of the world's trade.

The initiative would primarily involve more than 60 countries along the routes, but the Chinese have said it is open to all countries that "share the same goals".

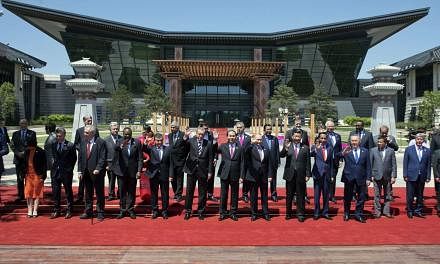

So it is that more than 1,200 delegates from 110 countries, including Singapore, and 61 international organisations will attend the forum.

ECONOMIC MOTIVATIONS

As the Chinese economy slows - from 10.6 per cent in 2010 to last year's 6.7 per cent, the slowest in 26 years - it needs to find new sources of growth, especially for its construction and engineering companies, analysts have said.

China also seeks to export overcapacity in its industries such as steel, cement and aluminium, and help its firms go international. China wants to use the initiative to develop its less developed regions.

GEOPOLITICAL AND SECURITY CONSIDERATIONS

While China has styled the BRI as a plan for economic cooperation with the rest of the world, many outside China see it as its way to dominate Asia again.

China had dominated the region, particularly at the height of the Qing dynasty in the 18th century, but lost its influence after the fall of the dynasty in 1911.

China is expanding its influence by binding other nations more closely to it economically, said Mr Tom Miller, author of China's Asian Dream: Empire Building Along The New Silk Road, at a talk recently.

There is also a security element. Beijing hopes to bring greater stability through economic development to Xinjiang, a poor region which has had outbreaks of violence.

FUNDING AND RISKS

The US$100 billion (S$141 billion) AIIB was set up in part to fund infrastructure projects of the BRI, as was the US$40 billion Silk Road Fund.

There is also the US$100 billion New Development Bank, set up by the Brics countries - Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa.

China's own banks have also pledged to lend to BRI projects.

However, with the Asian Development Bank having estimated that the Asian region alone needs US$1.7 trillion worth of infrastructure building annually from 2016 to 2030 to maintain its growth momentum, more funds are needed.

There is thus a need for the private and public sectors to come together and for the better-off countries to help financially, said Mr Zhang Yunling of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

To involve the private sector, however, there is a need for transparency in how the funds are allocated, analysts say. This is because private investors will not get involved unless they are sure the funds will be used effectively.

It has been pointed out that corruption and wasteful bureaucracies are common among nations on the routes. Addressing investors' concerns is a huge challenge for China.

PROGRESS SO FAR

Chinese officials have said that since 2013, the country has invested more than US$50 billion in countries along the trade routes.

In addition, they said, 56 economic and trade cooperation zones have been built by Chinese businesses, generating nearly US$1.1 billion in tax revenue and creating 180,000 local jobs.

But many projects considered to be part of the BRI predate the initiative. For example, the International Centre of Boundary Cooperation, a free trade zone that straddles the border between China and Kazakhstan in the city of Horgos (also known as Khorgos), was set up in 2011 but is now part of the BRI.

MIXED RECEPTION

Developing countries along the routes which are hungry for infrastructure welcome the BRI. These include Asean countries like Laos, Cambodia, the Philippines and Indonesia, although there is some wariness of China's intention to influence the region politically.

China's main rival, the United States, has shown little interest.

Its officials were non-committal when Mr Xi, at his meeting with US President Donald Trump, said China welcomed US participation in it.

Japan, which had earlier shown little interest, appears to have changed its mind. It is sending Mr Toshihiro Nikai, secretary-general of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party, to the forum.

The European Union has said that projects along the new trade routes should be open to Europeans.

As some analysts have said, there is a worry among countries and companies about missing out on what could be the largest trading collaboration in the world for many years to come.

READ PART 2 HERE: KEY STOPS ON CHINA'S NEW SILK ROAD

Join ST's Telegram channel and get the latest breaking news delivered to you.

A version of this article appeared in the print edition of The Straits Times on May 11, 2017, with the headline China makes tracks on modern Silk Road. Subscribe