LONDON (FINANCIAL TIMES) - The Omicron coronavirus variant that emerged in southern Africa has sparked global alarm owing to its unprecedented set of genetic mutations.

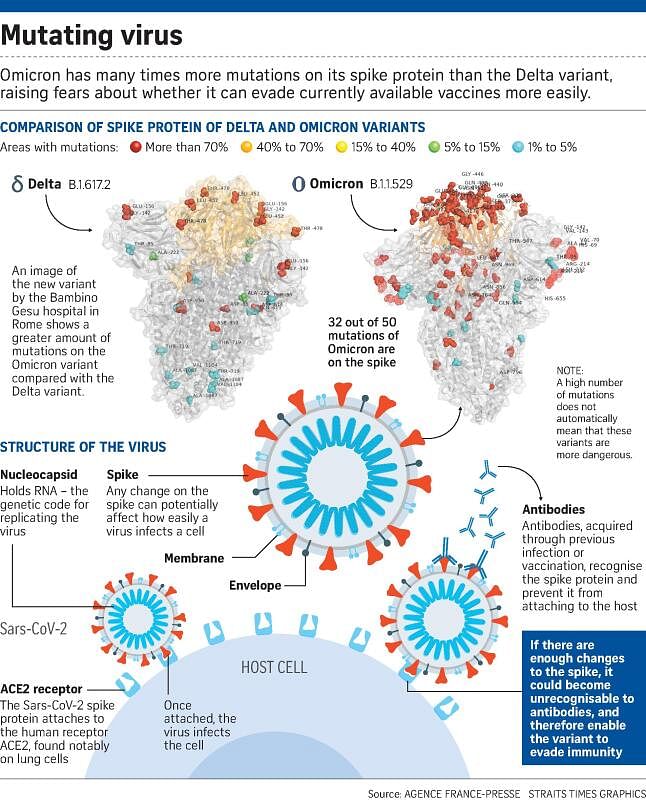

Its 50 mutations include more than 30 on the spike protein, the exposed part of the virus that binds with human cells. These could make it more transmissible than the dominant Delta variant and more likely to evade the immune protection conferred by vaccines or previous infection.

Why is Omicron causing such concern?

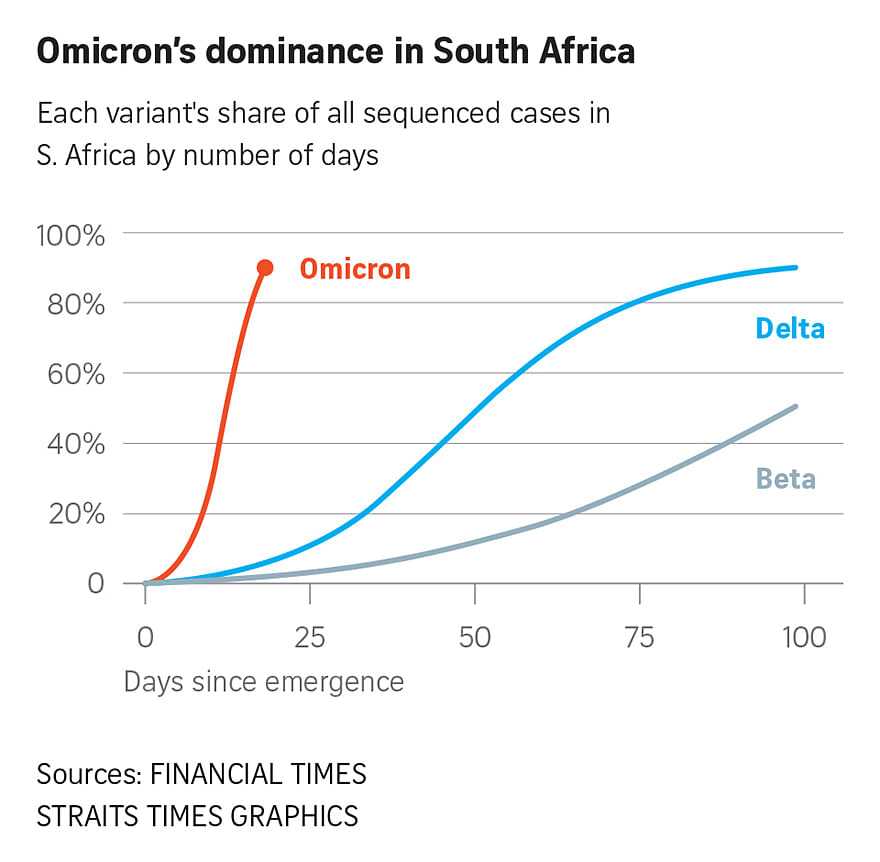

Scientists are worried for two main reasons. One is epidemiological and relates to the speed with which the variant first detected this month is spreading in South Africa, particularly in Gauteng province that includes the cities of Johannesburg and Pretoria.

Omicron's distinctive mutation pattern means that conventional PCR tests can distinguish it from Delta and other variants, without the need for full genome sequencing. Testing has showed it is responsible for more than 90 per cent of infections in Gauteng.

At the same time analysis of wastewater in Pretoria for traces of the Sars-Cov-2 virus - an indicator of outbreak size - suggested that infections had surged close to levels last seen during the Delta wave six months ago.

The other cause for concern is Omicron's highly unusual genetic profile. Jeffrey Barrett, director of the Covid-19 Genomics Initiative at the Wellcome Sanger Institute, described the strain as "an unprecedented sampling" of mutations from four earlier variants of concern: Alpha, Beta, Gamma and Delta. There are other genetic changes not seen before whose significance is as yet unknown, he added.

Worryingly, said Jacob Glanville, a computational immunologist and founder of US therapeutics company Centivax, 15 of the mutations were on the "receptor binding domain" - which acts like a "grappling hook" for the Sars-Cov-2 virus to enter human cells.

These mutations help the virus circumvent the body's immune defences because it is trained by vaccines or previous infection to fight the original Wuhan strain. By comparison, the Delta variant that has come to dominate the pandemic worldwide reduced the effectiveness of vaccines with just three mutations in this region.

In an Omicron briefing on Monday (Nov 29), Jonathan Van-Tam, England's deputy chief medical officer, said it was "likely" there would be an impact on the effectiveness of vaccines.

Where did Omicron come from? Is it really more dangerous than Delta?

As Sars-Cov-2 replicates, errors in the copying process occasionally change some of the 30,000 biochemical letters in its genetic code - typically at a rate of two mutations per month.

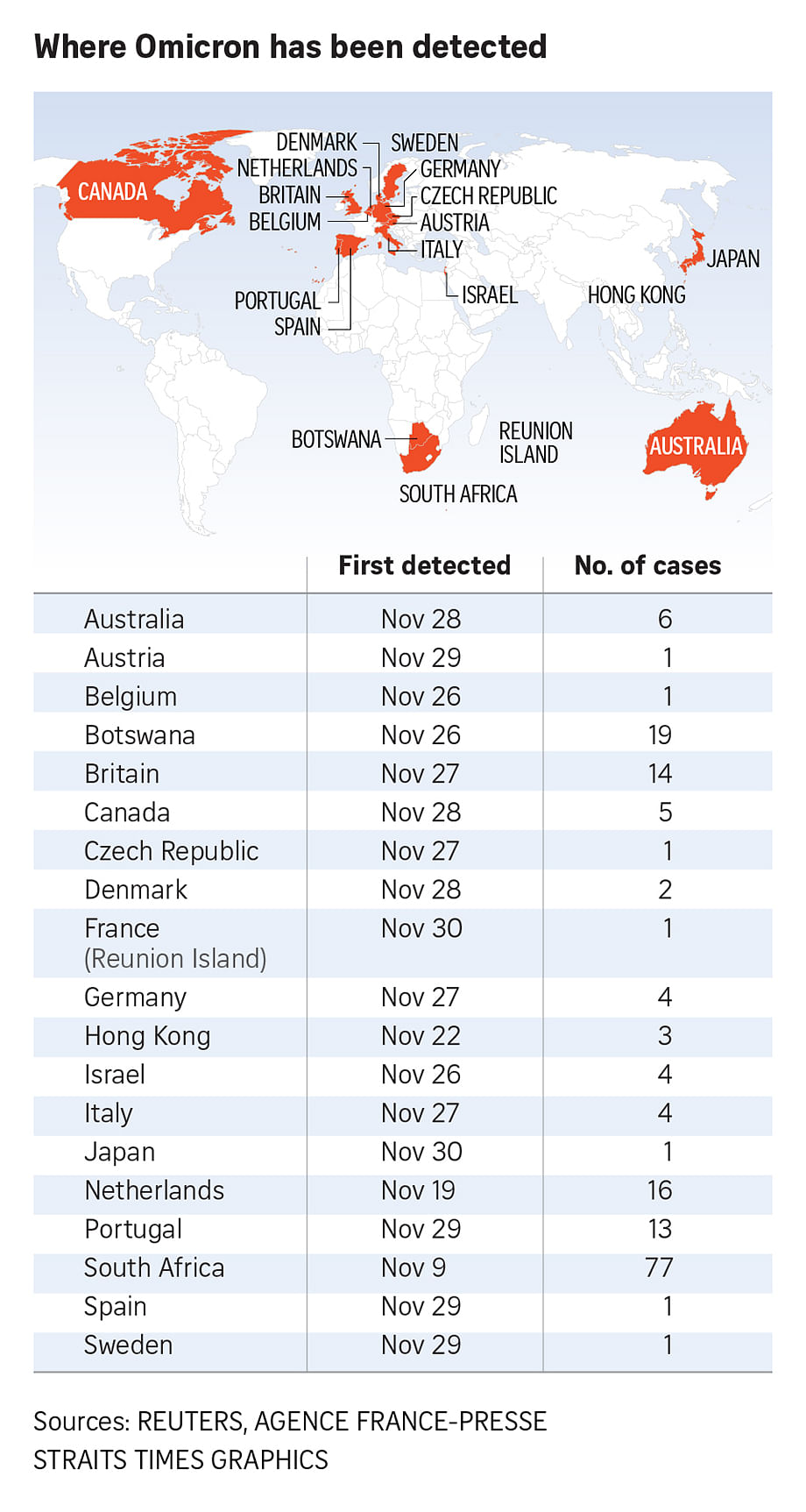

Though Omicron was first detected in samples from Botswana and South Africa, no one knows for sure where it originated and how it accumulated so many changes.

But scientists believe that the variant is likely to have evolved in a single individual whose immune system was compromised through medical treatment or disease - an "evolutionary gym" as Sharon Peacock, professor of public health and microbiology at the University of Cambridge, put it.

Slawomir Kubik, a genomics research expert at Geneva-based biotech Sophia Genetics, said many of Omicron's mutations came "completely out of the blue" and had not been observed before in other strains.

Therefore, scientists "have very little visibility on what these new mutations are doing to how the virus works", he explained, adding that once it began to spread more widely its "true fitness" would become clear.

Some of the mutations indicate increased transmissibility, while changes in the genetic code make it harder for the immune system, trained by existing vaccinations or previous infection with another variant, to tackle a new strain. But it will take researchers several weeks or months to work out the interactions between them and their cumulative impact.

Even if Omicron proves to be the most infectious Sars-Cov-2 variant so far, there is no clear evidence yet from South Africa or anywhere else about whether it will turn out to cause worse symptoms. "It could go either way," said Glanville. "The mutations could make it worse or the mutations could make it more benign."

Is there any evidence that Omicron produces less severe disease than previous variants?

Several doctors in South Africa have remarked that people infected with Omicron so far seem to show milder symptoms than those in Delta patients. Many are asymptomatic. Others suffer from coughs, fatigue, body and head aches. No deaths have been attributed yet to the new variant.

"I think it will be a mild disease, hopefully," said Angelique Coetzee, chair of the South African Medical Association. "We're confident we can handle it."

Many experts, however, caution against reaching such conclusions when the variant has not been properly researched. They noted that, so far, it had mainly infected young and healthy people who are less susceptible to severe symptoms, whatever variant is responsible.

Michael Mina, an epidemiologist at Harvard Medical School, pointed out that the number of reported cases in the Pretoria region was relatively small compared with the high viral load detected in wastewater. And while that could mean most infections were so mild that they were going undetected, it was more likely that wastewater was a leading indicator and that case numbers would catch up. "There isn't much in this virus sequence suggesting it should be very mild," he said.

Even if Omicron caused milder symptoms on average, the total toll of hospitalisations and deaths would be greater if it is much more infectious and better at escaping human immune protection.

How well placed is the world to face the threat?

Many scientists supported the immediate response of banning travel from countries where Omicron was spreading fast. "The objective of the border closures and travel restrictions that have been announced is to limit the global spread of the variant," said Francois Balloux, director of the UCL Genetics Institute in London.

He continued: "If were more transmissible than Delta, this strategy is most unlikely to succeed in the long term but might allow gaining some time to further increase vaccination rates, including third doses, and deploy promising drugs currently in the pipeline."

If Omicron spreads around the world and leads to a marked increase in hospitalisations and deaths, then governments may have to reimpose social distancing measures or intensify existing restrictions - which in the worst case could mean a return to lockdowns.

Despite the many uncertainties, most scientists are more confident than they were when the earlier Alpha and Delta waves arrived.

The new variant is "most unlikely to fully escape immunisation provided by vaccination and prior infection", said Balloux. "With high vaccination rates and promising drugs on the horizon, a possible B.1.1.529 wave should be far less painful to weather than the Alpha and Delta ones."

Another positive is that, because of the efforts of South African scientists, countries have been warned about the risks posed by Omicron far sooner than they were about Delta, which had already spread widely from India before the world was alerted.