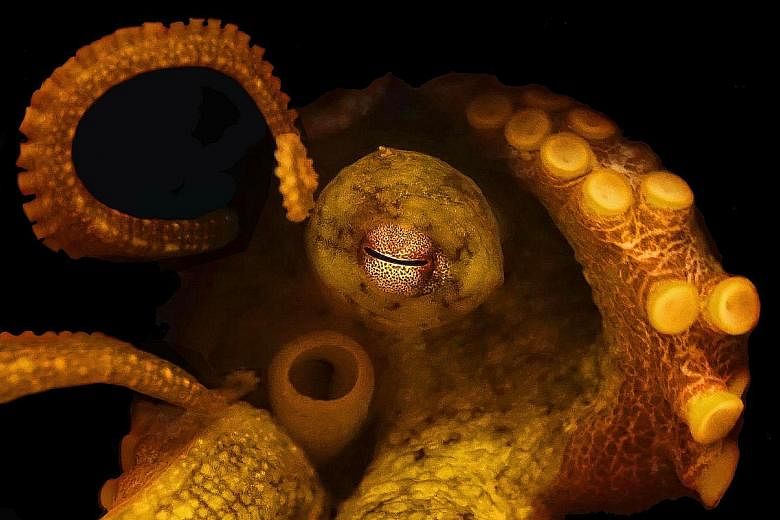

Scientists have unlocked the genetic secrets of one of earth's underwater wonders: the octopus, whose eight sucker-studded arms bestow it an otherworldly appearance and large brain places it among the smartest invertebrates.

It is the first complete genome of an octopus or any species of cephalopod, the class of molluscs which includes squid, cuttlefish and nautiluses.

"Octopuses and other cephalopods are indeed remarkable creatures," said University of Chicago biology graduate student Caroline Albertin, who helped lead the study published in the journal Nature.

"They can camouflage themselves with skin that can change its colour and texture in the blink of an eye. They have eight prehensile, sucker-lined arms that they can use to grasp, manipulate and even, strangely enough, taste objects, as well as complex, camera-like eyes and large, elaborate brains that allow them to be active predators with complex behaviours."

The team, which included Japan's Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University (OIST) and the University of California at Berkeley, sequenced the genome of the California two-spot octopus (Octopus bimaculoides), a relatively small, grey-brown species with two iridescent blue spots on either side of its head.

Its genome was large, nearly the size of the human one and much bigger than those of other sequenced invertebrates such as flies, snails or oysters. Among its roughly 33,000 genes, some 3,500 are found in no other type of animal, with many of these octopus-specific genes active in the brain, suckers, retina and in camouflage ability.

The octopus genome encodes several large gene families that may hold the key to how the animal wires up its complex brain - these gene families are involved in regulating brain development in other animals, but they are vastly expanded in the octopus, said the Japanese institute. Hundreds of other genes that are common in cephalopods but unknown in other animals were also found.

Some of these are implicated in the dynamic skin of the creatures, allowing for spectacular camouflage.

Octopuses are carnivorous, ripping prey with a hard beak and can employ venom while hunting. They can also regenerate lost limbs and squirt dark ink to elude predators.

The cephalopod lineage is ancient, arising more than half a billion years ago.

The first octopuses appeared about 270 million years ago. Today, there are about 300 species.

Said Nobel laureate Sydney Brenner, founding president and distinguished professor of OIST: "They were the first intelligent beings on the planet."

Prof Brenner was fascinated with the great sophistication of their nervous system and initiated the octopus genome project.

The Japanese institute added that one reason the octopus fascinates scientists is that its brain became organised to be able to carry out incredible, complex tasks without adopting the principles of the vertebrate brain.

Further examination will tell if the building blocks of its nervous system are as radically different from those of vertebrates such as humans, as the octopus' abilities suggest, it added.

University of California Berkeley genetics professor Daniel Rokhsar said genome research is under way on other cephalopods, including the world's largest, the giant squid.

REUTERS, OKINAWA INSTITUTE OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY GRADUATE UNIVERSITY