WASHINGTON (NYTIMES) - The long-awaited special counsel report is complete, 675 days after Mr Robert Mueller was named to oversee the investigation into Russia's election interference, whether any Trump associates coordinated with that plot and whether President Donald Trump tried to obstruct justice.

Attorney General William Barr has the document and notified lawmakers. But it has yet to be made public, and the path to its potential release - or the release of the facts it contains - is complicated.

WILL THE REPORT BE MADE PUBLIC?

That remains to be seen. Some information is expected to come out because Mr Barr has to update Congress, but that does not mean the entire report will be public.

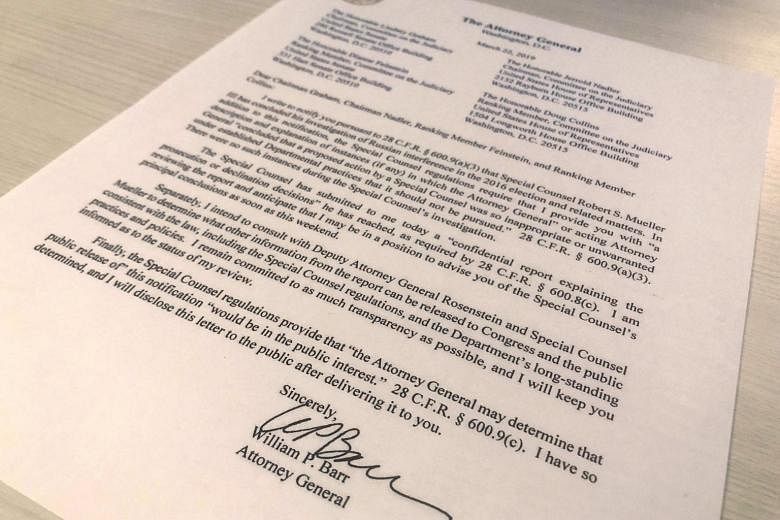

Mr Barr sent a letter to the leaders of Congress' judiciary committees that the special counsel investigation has been completed, which he is required to do, according to the special counsel regulation. Mr Barr said he was reviewing Mr Mueller's report and might be able to provide lawmakers with the special counsel's "principal conclusions" as early as this weekend.

The regulation also requires that Mr Barr tell the lawmakers whether he or his predecessors overseeing it opposed any significant step that Mr Mueller sought to take. Mr Barr said "there were no such instances" during the investigation.

The special counsel regulation sets no time frame or deadline for when Mr Barr must provide this information to Congress.

Mr Barr is required only to provide lawmakers with very basic facts. He would be operating within the guidelines of the regulation if he were to give Congress a bare-bones notification that Mr Mueller had concluded his work. In his letter on Friday (March 22), Mr Barr said he planned to consult with the deputy attorney general, Mr Rod Rosenstein, and Mr Mueller about what other details from the report could be given to Congress and the public.

According to the Justice Department's explanation of the regulation, published in the Federal Register in 1999, Mr Barr has to determine whether releasing the report, or portions of it, is in the public's interest. Mr Barr has said repeatedly that he would release as much as he could from the report within the parameters of the special counsel regulations.

But, first, Mr Barr and his aides will have to review the report to determine whether any information is classified or otherwise sensitive, or protected by privacy laws or executive privilege, which can be invoked for sensitive law enforcement materials.

The back and forth on what information Congress can and cannot have will most likely be drawn out and have to be resolved by a court.

WILL CONGRESS BE SATISFIED WITH A BARE-BONES REPORT?

No.

Senator Dianne Feinstein of California, the top Democrat on the Senate Judiciary Committee, has already called for the entire report, without redactions, to be provided to lawmakers.

"Regulations governing special counsel Mueller's investigation do not prohibit Attorney General Barr from disclosing Mueller's final report and investigative materials to Congress," Ms Feinstein said in February.

And the House overwhelmingly passed a resolution calling for the report to be made public - a largely symbolic move to pressure Mr Barr to publicly release it.

Democrats in the House have also made the case that seeing the report in its entirety is critical to their ability to conduct oversight and determine whether to move forward with impeachment proceedings.

"Congress could be the only institution currently situated to act on evidence of the president's misconduct," the chairmen of several House committees wrote in a Feb 22 letter to Mr Barr.

Further, they wrote, Congress should decide what should be redacted in the report.

Speaker Nancy Pelosi of California has said that she does not support impeaching Mr Trump without support from Republican lawmakers because it is too divisive for the country. Barring new shocking revelations about Mr Trump, Democrats would prefer to beat Mr Trump in the 2020 presidential election.

WHAT IF THE ADMINISTRATION REJECTS CONGRESS' REQUESTS?

Lawmakers have a few options to try to make public details of the investigation, though some could involve years of litigation.

They could start issuing subpoenas to Mr Barr, who could ignore them or refuse them. They could also subpoena Mr Mueller's testimony. The Justice Department is likely to resist those demands.

If that happens, lawmakers could hold them in contempt and ask the US attorney for the District of Columbia to prosecute. Lawmakers could also sue to try to force the Trump administration to hand over the requested material. Such litigation could go on for years.

The White House could also try to negotiate with Congress, such as making some witnesses available, but not all, said Prof Richard H. Pildes, a constitutional law professor at New York University Law School. The White House is also likely to challenge some requests and assert that the requested information is available to lawmakers through other means.

Lawmakers can also use their bully pulpits to pressure Mr Barr publicly for more information and tie up the Justice Department in hearings and subpoena fights that last for the rest of Mr Trump's time in office.

Will the president even see the report?

That is not clear.

Mr Trump is Mr Barr's boss, and there is nothing to stop Mr Barr from immediately sharing the report with the White House, Prof Pildes said. But doing so would violate the Justice Department's long-standing independence from the White House, said Prof Jack L. Goldsmith, a Harvard law professor who ran the department's Office of Legal Counsel during the George W. Bush administration.

And if the Mueller report includes grand jury testimony, which is protected under federal law, the number of people permitted to see the report shrinks significantly. Mr Trump, as president, would be permitted to see it in certain circumstances.

For example, according to a 1993 opinion by the Justice Department's Office of Legal Counsel, grand-jury information may be disclosed to the president if it relates to his role in helping the department decide how to enforce the law, or if it relates to a national security threat.

In another Justice Department legal opinion, written in 2000, the president may have access to grand jury material if it is used as part of his consideration for a pardon. There has been a great deal of discussion about whether Mr Trump would give presidential pardons to his former aides who have been charged in Mr Mueller's investigation, such as Mr Paul Manafort, his former campaign chairman who was sentenced to 7 1/2 years in prison in two cases.

WHAT IF TRUMP TWEETS INACCURACIES ABOUT THE FINDINGS?

Even if Mr Mueller and Mr Barr know that what Mr Trump is saying publicly is not true, there is no apparent legal duty for the Justice Department to correct the president.

WILL THIS BE THE FINAL WORD ON "COLLUSION"?

Unlikely.

First, collusion has no legal definition, though it has become a term of art as a shorthand reference to the Russia investigation. A key question in the special counsel investigation concerns whether Mr Trump or his campaign was coordinating with Russia to try to affect the outcome of the 2016 presidential election. If Mr Mueller's investigation ends without charging Mr Trump or his aides with conspiracy, some may interpret that to be a "no collusion" finding.

Mr Trump consistently cites government officials and the lack of collusion charges as evidence that there was never collusion between his campaign and Russia.