MIAMI • Behind a locked door aboard Norwegian Cruise Line's newest ship is a world most of the vessel's 4,200 passengers will never see. And that is exactly the point.

In the Haven, as this ship within a ship is called, about 275 elite guests enjoy not only a concierge and 24-hour butler service, but also a private pool, sun deck and restaurant, creating an oasis free from the crowds on the Norwegian Escape.

If Haven passengers venture out of their eyrie to see a show, a flash of their gold key card gets them the best seats in the house. When the ship returns to port, they disembark before everyone else.

"It was always the intention to make the Haven somewhat obscure so it wasn't in the face of the masses," said Norwegian's former chief executive Kevin Sheehan, who helped design the Escape with the hope of attracting a richer clientele. "That segment of the population wants to be surrounded by people with similar characteristics."

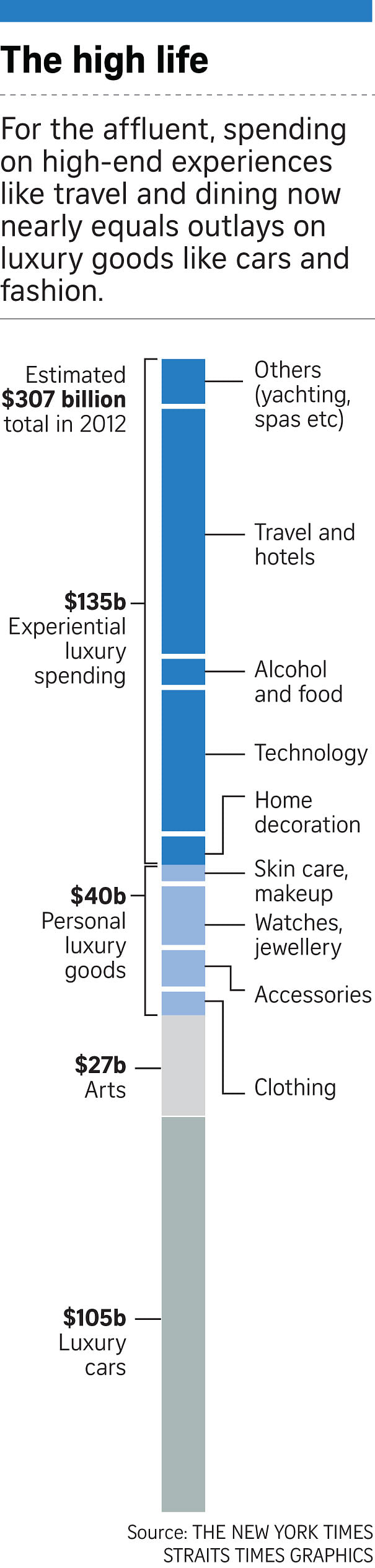

With rising disparities in wealth, the gap is widening between the highly affluent, who find themselves behind the velvet ropes of today's economy, and everyone else.

It represents a degree of economic and social stratification unseen in the United States since the days of president Teddy Roosevelt, financier J.P. Morgan and the rigidly separated classes on the Titanic a century ago.

What is different today, though, is that firms have become much more adept at identifying their top customers and knowing which psychological buttons to push. The goal is to create extravagance and exclusivity for the select few, even if it stirs up resentment elsewhere. In fact, research has shown, a little envy can be good for the bottom line.

When top-dollar travellers switch planes in Atlanta, New York and other cities, Delta ferries them between terminals in a Porsche, what the airline calls a "surprise- and-delight service".

Last month, Walt Disney World began offering after-hours access to visitors who want to avoid the crowds. You basically get the Magic Kingdom to yourself.

When Royal Caribbean ships call at Labadee, the cruise line's private resort in Haiti, elite guests get their own special beach club away from fellow travellers.

"We are living much more cloistered lives in terms of class," said Mr Thomas Sander, who directs a project on civic engagement at the Kennedy School at Harvard. "We are doing a much worse job of living out the egalitarian dream that has been our hallmark."

Mr Emmanuel Saez, a professor of economics at the University of California, Berkeley, estimates that the top 1 per cent of US households now controls 42 per cent of the nation's wealth, up from less than 30 per cent two decades ago. The top 0.1 per cent accounts for 22 per cent, nearly double the 1995 proportion.

But even as income inequality and the wealth gap stoke the discontent that has emerged as a powerful force in this year's presidential election, for US businesses it represents something else entirely. From cruise ship operators and casinos to amusement parks and airlines, the rise of the 1 per cent spells opportunity and profit.

Today, ever greater resources are being invested in winning market share at the very top of the pyramid, sometimes at the cost of diminished service for the rest of the public. While middle-class incomes are stagnating, the period since the end of the Great Recession has been a boom time for the very rich and the businesses that cater to them.

From 2010 to 2014, the number of US households with at least US$1 million (S$1.35 million) in financial assets jumped by nearly one-third to just under seven million, according to a Boston Consulting Group study. For the US$1 million-plus cohort, estimated wealth grew by 7.2 per cent annually from 2010 to 2014, eight times the pace of gains for families with less than US$1 million.

In many ways, the rise of the velvet rope reverses the great democratisation of travel and leisure, and other elements of American life, in the post-World War II era. As the jet set gave way to budget airlines, in places like airports and theme parks even the wealthiest often rubbed shoulders with the hoi polloi.

These days, whether the provider is a private company or a public agency, special treatment for the very rich is not personal - it is business. Late last year, public officials in Los Angeles agreed to lease a separate facility at its international airport to a private firm that will serve celebrities or anyone else willing to pay US$1,800 to skip traffic jams and lines at the main terminals.

Of course, it could be more extreme, and in the past it was.

The Titanic, in the early 20th century, separated the different classes of travellers with metal gates. In the 19th century, French railways refrained from putting roofs on third- class wagons so that passengers who could afford more expensive second-class seats would not hesitate to spend a few extra francs.

What is new is just how far big US companies will now go to pamper the biggest spenders.

For example, as luggage-toting guests boarded Norwegian's Breakaway ship in New York recently, cramming into a handful of lifts, there was ample room in one bank. But it was off limits to anyone but Haven guests going to the top decks. Not far away, in the ship's theatre, red velvet ropes cordoned off a section up front for Haven passengers.

At SeaWorld, a family of four can jump to the front of the line and score the best seats for rides and shows for an extra US$80, in addition to the basic US$320 admission. For people who want something more exclusive, there is Discovery Cove, next door to SeaWorld's traditional park in Orlando.

Forget merely swimming with dolphins. Today, parents can relax at a cabana and beach of their own, while their budding marine biologists spend the day with a trainer, feed the park's birds, otters, nurse sharks and other creatures.

There are no lines to cut here: daily attendance is capped at 1,300. A day at Discovery Cove can easily cost US$1,000 for a family of four.

Next year, Crystal Cruises will begin an airborne version of one of its luxury ships: a customised Boeing 777 that ferries passengers on 14- or 28-day trips around the world.

As firms separate their clientele, a debate has developed over just how obvious the distinctions should be. Some experts say it is best to be open about what amounts to a money-based caste system. "It's about transparency. What customers hate is when you're trying to hide stuff and aren't being honest with them," said Mr David Clarke, who works with leisure industry giants as a principal at PricewaterhouseCoopers.

Many companies, though, have discovered that offering ordinary customers just a whiff of the rarefied air can enhance the bottom line, even if it stirs a certain amount of envy and resentment.

As coach passengers pile into giant 747s and A-380s, for example, "a glimpse of a shower or private suite creates a marker in people's minds", said Mr Alex Dichter, a director at McKinsey who works with major airlines.

But the gap between the privileged and the rest may leave everyone feeling uneasy, said Yale management professor Barry Nalebuff. "If I'm in the back of the plane, I want to hiss at the people in first class. If I'm up front, I cringe as people walk by."

NEW YORK TIMES