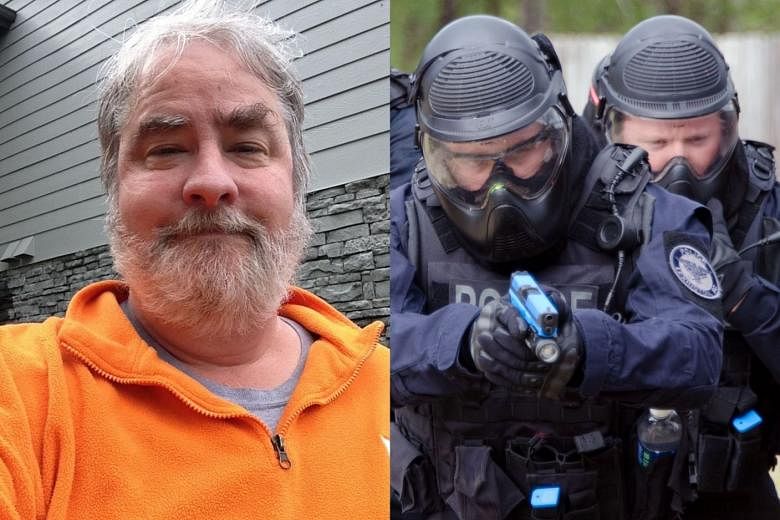

NEW YORK (NYTIMES) - Mark Herring was at home in Bethpage, Tennessee, one night in April 2020 when the police swarmed his house.

Someone with a British accent had called emergency services in Sumner County and reported having shot a woman in the back of the head at Herring's address. The caller had threatened to set off pipe bombs at the front and back doors if officers came, according to federal court records.

When the police arrived, they drew their guns and told Herring, a 60-year-old computer programmer and grandfather of six, to come out and keep his hands visible.

As he walked out, he lost his balance and fell. He was pronounced dead that same night at a nearby hospital. The cause of death was a heart attack, according to court records.

Herring had been a victim of "swatting," the act of reporting a fake crime in order to provoke a heavily armed response from the police.

The caller was a minor living in the United Kingdom, according to federal prosecutors. But the caller knew Herring's address because Shane Sonderman, 20, of Lauderdale County, Tennessee, had posted the information online, prosecutors said.

On Wednesday (July 21), Sonderman was sentenced to five years in prison after he pleaded guilty to one count of conspiracy.

Herring was targeted because he refused to sell his Twitter handle, @Tennessee, according to his family and prosecutors.

He knew people wanted his handle, which he chose because of his love for the state, where he had been born and raised, and had rebuffed offers of US$3,000 to US$4,000 (S$4,000 to S$5,400) to sell it, his daughter Corinna Fitch, 37, said in an interview.

He was among at least a half-dozen people who were targeted by Sonderman and "co-conspirators," who created fake online accounts to find social media users with catchy names, prosecutors said.

Sonderman and his co-conspirators would then contact the holders of those names and ask them to give them up so they could sell them.

If they refused, "Sonderman and his co-conspirators would bombard the owner with repeated phone calls and text messages in a campaign of harassment," prosecutors said.

"Gonna need the instagram account… or i will continue to swat and harass you and your family," Sonderman or one of his co-conspirators wrote in March 2020, according to court documents.