NEW YORK • If plants could be stars in a cowboy film, the scarlet gilia would be one of the meanest wildflowers west of the Mississippi.

You can find it standing tall among the sagebrush on mountainsides, its red flowers blazing. Drought can't always stop it. Shade won't faze it. And when mule deer and elk start grazing on it early in the season, it comes back bigger and stronger, with more defences and a posse of new plants.

Biologists call outlaw plants like these the overcompensators.

"It's a little counter-intuitive," said University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign graduate student Miles Mesa, who led a new study into these types of plants. "After some animal comes by and eats it, the plant actually does better."

In the study published this month in the journal Ecology, scientists showed for the first time that in an experiment, damaging some plants set off a molecular chain of events that caused them to grow back bigger, and produce more seeds and chemical defences simultaneously.

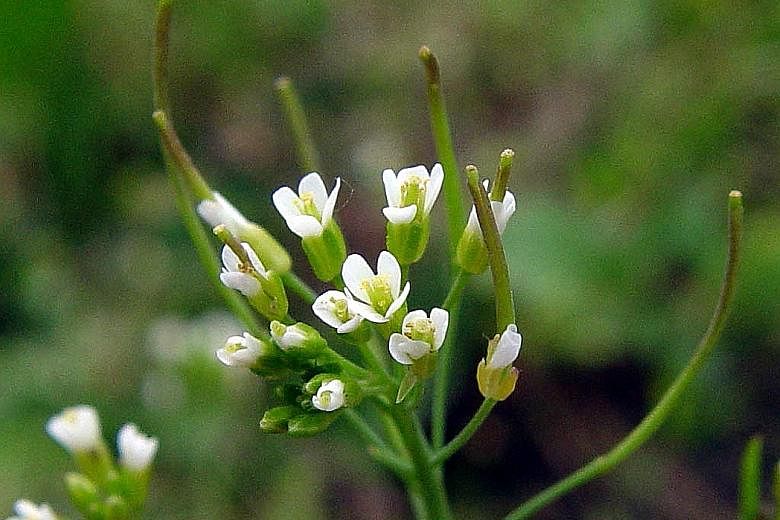

At the genetic level, the two tactics for plant survival worked hand in hand - at least in Arabidopsis thaliana, a kind of mustard plant often used for research.

Professor Ken Paige, an evolutionary ecologist also at the University of Illinois and principal investigator of the study, first observed overcompensation in the scarlet gilia in 1987. He described plants that would make more flowers, stems and seeds when their main stems were cut off or eaten.

At the time, being eaten was believed to be bad for plants - always.

It took a decade's worth of seeing the contrary for other biologists to believe it. Prof Paige started looking for a molecular mechanism behind overcompensation in some versions of Arabidopsis.

As he damaged their main stems, he started seeing signs that not only did they get bushier and produce more seeds, but they also ramped up their chemical defences.

At one point in time, theory pitted regrowth, also known as tolerance, against defence: with limited energy, a plant had to pick one or the other. But in the past decade, more researchers can't find a trade-off, said Professor Anurag Agrawal, an ecologist at Cornell University who studies plant-herbivore interactions and was not involved in the study. Prof Paige thinks a special process at the molecular level helps plants that overcompensate employ both strategies.

Most plants respond to damage with a process called endoreduplication, in which a cell can copy its DNA over and over without splitting into two cells. This gives the plant bigger cells with multiple energy factories to accomplish a variety of tasks.

Many damaged plants only show minimal levels of endoreduplication. But the overcompensators go into overdrive with the process.

In the case of the study's mustard plants, they were able to grow bigger and also produce glucosinolate, the sulphurish, bitter chemical compound in mustard, kale, cabbage and horseradish.

And the new research has found that when it comes to building up tolerance or defences, for at least some plants, you can't have one without the other.

"What this paper shows is that, in practice, defence and regrowth actually go hand in hand because the genetics of defence and regrowth are similar," said Assistant Professor Josh Banta, a biologist at The University of Texas at Tyler, who was not involved in the study.

"Like it or not, theory be darned."

But even the baddest cowboys are not immortal, the researchers found. If they cut the main stem and 75 per cent of its leaves, even overcompensators can't rebound.

This tough guy tactic may be a special case, said Prof Agrawal, but Mr Mesa and Prof Paige think it could be generalised to many other plants. Depending on much that turns out to be true, future research could one day help farmers grow super crops that could make more food without having to use as many pesticides.

But as the story often goes for basic genetic research on crops, results that could be applied are a way off.

NYTIMES