With both ankles shackled to a post, 27-year-old Sulaiman could do little but stand, sit and sleep all day.

For six months, home for the Indonesian with mental illness has been a rickety stilthouse in a remote village nestled among rice fields and mountains of Bogor, a city south of the capital Jakarta.

"I'm bored and these irons make my legs feel numb as if they have been rolled over by a tractor," he told The Straits Times.

He used to be secured in wooden stocks, but he managed to break free of them. They have since been replaced with the iron chains.

His mother Rukmini, 45, a rice farmer said her heart broke when she first had to lock him up. "I cried, no mother wants to do this to her own son, but I have no choice."

According to official figures, Sulaiman is among more than 18,000 Indonesians with mental illness who are still subjected to pasung, where they are kept in restraints or in a confined space. This even though the decades-old practice was outlawed in 1977.

It is not uncommon for patients to be locked in chains and wooden stocks, and isolated in cramped and filthy chicken coops or goat sheds for years, activists and officials said.

This is a result of the lack of mental health services, trained caregivers and psychiatrists as well as little awareness of psychosocial and intellectual disabilities, said Mr Nahar, a social rehabilitation director at Indonesia's Social Affairs Ministry.

"We know that it's still happening but we are not closing an eye to their plight," he said. "We are serious about helping them despite our less than ideal situation."

President Joko Widodo wants to put an end to the practice by December next year. That is why teams of caregivers have been visiting rural villages since January to free patients from their restraints and provide medical treatment.

"Many who do this are poor and uneducated who have no idea how to deal with mental patients," said Mr Nahar. "So we are now focusing on education."

Only about half of the 445 general hospitals in the country offer mental healthcare services, but about 400,000 Indonesians have severe mental illnesses. Many go unreported, added Mr Nahar.

For some families, the stigma and shame of having family members with mental illness have caused them to shy away from seeking professional help.

For others, superstitious beliefs have steered them towards traditional healers instead.

Sulaiman, for instance, was taken to numerous village shamans for treatment when he "turned crazy" three years ago, after his childhood love got married and he was sent off to a religious boarding school.

A neighbour, Madam Sobariah, 45, said: "The faith healers say he has been possessed by demons. He hits people including his parents with sticks and rocks until they are black and blue. He steals chicken and fruits... he destroys crops."

Human Rights Watch (HRW) group in its report Living In Hell released last month, called pasung a "widespread and brutal practice" that takes place not only in rural homes, but also in private and public rehabilitation centres.

HRW disability rights researcher Kriti Sharma said the group recognises that the ministries involved are "keen to work together on this issue, but it is time for the government to translate the rhetoric in Jakarta into practice on the ground.

Indonesian Mental Health Association chairman Yeni Rosa Damayanti said pasung is not unique to Indonesia, but rampant in the Philippines, Laos and Cambodia, Nepal, India and Bangladesh.

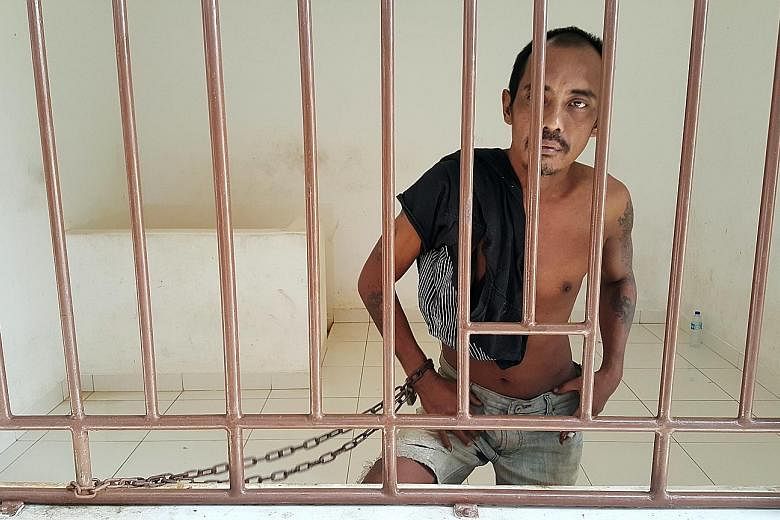

A visit by The Straits Times to a privately-run Galuh Rehabilitation Centre in Bekasi, an area in the capital's outskirts, found a few hundred patients with mental illness held in an open hall separated by iron bars.

A few were isolated in smaller rooms, including one who was shackled to a bar because of his penchant for destroying fittings such as water taps and ceiling boards.

Owner Suhanda and many other activists say conditions, however, have improved at the centre thanks to donations and caregiver training.

"We used to chain up a lot of patients in the past because we don't have enough manpower to look after everyone. Fights among patients can break out anytime and turn ugly," said Mr Suhanda.

"While we don't want them to hurt one another, we now understand they are also human so we have to treat them like one, so no more shackling unnecessarily."