MILAN (Reuters) - When Giulia Spada gets a traffic ticket, she pops along to her local post office to pay it. Even though that can mean standing in line for an hour.

"I found out recently you can do it online but I'm still not convinced," said the 33-year-old postgraduate student from Pavia, a town near Milan.

"It's not that straightforward, and it's just easier to go to the post office."

Spada's experience epitomises Italy's struggles with the Internet.

Bringing superfast Internet to all Italian homes by 2020 has become one of the pillars of Prime Minister Matteo Renzi's push to galvanise a stagnant economy, create jobs and open businesses to the global market.

But citizens have been less eager to embrace the digital drive than their 41-year-old premier, creating a headache for broadband firms and content providers: rolling out a fast network is no guarantee of commercial demand and returns for their multi-billion-euro investments.

Even where provision exists for superfast broadband - defined as more than 30 megabytes per second (Mbps), generally enough to allow several members of a household to use the Internet and stream video at the same time, take-up is slow.

Italy has the European Union's fourth largest economy, but comes last of the 28 members in Internet usage, EU data shows. A third of the population has never used the web and only just over half of households subscribe to fixed-line broadband.

Only mobile broadband take-up is in line with the EU average as Italians use phones to listen to music and play video games.

But the use of online banking and shopping remains limited, due to an ageing population, poor English skills, a distrust of uploading personal data and a fear of overly complex procedures.

HIGH-SPEED HEADACHE

Even those like Spada, who has set up broadband at home to move more transactions online, end up facing a tangle of red tape that makes the very idea of using a public site a headache.

When she tried to file for an exemption to paying her TV licence fee, she was told first to apply on a separate site for a PIN-number, which would take two weeks to arrive - after the deadline.

"So I went back to the post office and ended up paying 6 euros to file the form via registered mail," she said. "The system is improving, but it's frustrating when it doesn't work."

Worryingly for Renzi, that doubt about the usefulness of the Internet seems to extend to the small businesses that are the backbone of the economy.

Only around 40 per cent of firms that were listed in a register of 'innovative startups' at the end of last year had a functioning website, according to a study by the digital marketing agency Instilla.

It all suggests a lack of the demand that the telecoms providers say they need in order to justify investing in faster connections.

Italy is second to last in the EU for the roll-out of superfast broadband after providers, also hampered by regulatory uncertainty, held back on investments for years.

But even though a superfast connection is available to more than 40 per cent of households, only 3 per cent have taken it up. The average connection speed in Italy is 7.4Mbps, according to the online content distributor Akamai.

Broadcasters and entertainment providers appear to be finding it hard to commit. Catch-up TV is still virtually unheard-of in Italy, and the on-demand video entertainment service Netflix launched there only last October.

But the telecoms firms say demand will only arise once big-ticket films, television shows and sports events are being offered online - preferably exclusively and in bandwidth-guzzling high definition, suitable for big television screens.

"I can bring the horse to the fountain," Telecom Italia chairman Giuseppe Recchi told shareholders on Wednesday, "but I can't make it drink... Even if we are ready with the networks of the future today, people still do not have sufficient incentives to use them: watching videos online or interacting digitally with public administration."

DIGITAL ID

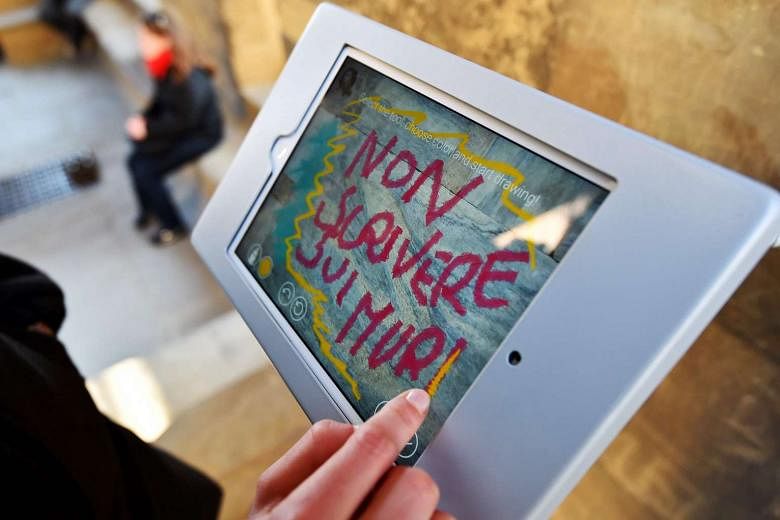

And that, at least, is where Renzi hopes government can help, offering more and more public services to citizens with digital IDs to create a "faster, more agile, less bureaucratic Italy" - while at the same time scaling down personal, over-the-counter services.

Whether that really means all of Italy has to have superfast broadband right away, with an expensive fibre-optic connection all the way to the home, is widely debated.

The debt-laden former state monopoly Telecom Italia and rival provider Fastweb argue that it is sufficient for now, particularly in low-density, high-cost rural communities, to have a copper cable covering the last stretch from the roadside cabinet to homes, with the potential to upgrade later.

"Fibre to the home everywhere is just uneconomical," said Mark Vos, a senior partner at Boston Consulting Group.

The fact is that running fibre all the way into homes costs three times as much as using the existing copper connection. Renzi, undeterred, has asked the utility firm Enel to use its pylons and pipe ducts to do the job, creating a competitor to Telecom Italia.

But Vos agrees with the other part of Renzi's strategy:"It's time Rome focused on getting the basic digital public service layer right, because otherwise we have this fantastic digital asset and nobody using it."

There may be some comfort for the prime minister in figures showing that the percentage of small and medium-sized firms' business done online jumped to 8.2 per cent last year from 4.9 per cent in 2014.

To really get the ball rolling, some say the government just needs to emulate what it did in the 1960s, when it put Roman schoolteacher Alberto Manzi on an evening television show to teach Italians how to read and write.

As Maestro Manzi said: "It's never too late."