LONDON (NYTIMES) - Bank robbers wear masks and escape in vans with stolen licence plates. Kidnappers compose ransom letters from newsprint to elude handwriting experts. Burglars target houses with the upstairs window ajar.

Cyber criminals do much the same.

They hide behind software that obscures their identity and leads investigators to look in countries far from their actual hideouts. They kidnap data and hold it hostage. And they target the most vulnerable companies and people whose information is poorly protected.

Cybercrimes, like the global ransomware attack that began on Friday (May 12) and has affected hundreds of thousands of computers in more than 150 countries, are in a way an updated version of ancient criminal methods.

And in the global search for the criminals that continued on Sunday, investigators are following much the same process that detectives in the physical world have used for decades: secure the crime scene, collect forensic evidence and try to trace the clues back to the perpetrator.

But for all of their similarities to traditional crimes, cyber attacks have major digital twists that can make them much harder to solve and can greatly magnify the damage done.

The latest attack has claimed at least 200,000 victims worldwide, according to an estimate on Sunday by Europol, Europe's police agency, and new variants of the malware are emerging, leading security experts to warn that the fallout could spread as people return to work on Monday.

Such a large, complex and global crime outbreak means any hope of a successful investigation will require close teamwork among international law enforcement agencies - such as the FBI, Scotland Yard and security officials in China and Russia - often wary of sharing information with one another.

"With cybercrime, you can operate globally without ever having to leave your home," said Mr Brian Lord, a former deputy director for intelligence and cyber operations at Government Communications Headquarters, Britain's equivalent of the US' National Security Agency.

"Catching who did this is going to be very hard, and will require a level of international cooperation from law enforcement that does not come naturally."

The only institutional arrangement for international cooperation on cybercrime is the so-called Budapest Convention, whose membership is largely restricted to Western democracies, said Mr Nigel Inkster, a former assistant chief of Britain's secret intelligence service MI6.

Russia and China have refused to sign the agreement because it permits the digital equivalent of hot pursuit: A police force investigating a cybercrime can access networks in other jurisdictions without first seeking permission.

"Any investigation of the recent ransomware attack will have to be done by a coalition of the willing," Mr Inkster said.

There are signs a coalition is coming together, at least in parts of the international system. Europol said its team of cyber security specialists - made up of agents from countries such as Germany, Britain and the United States - was investigating the attack.

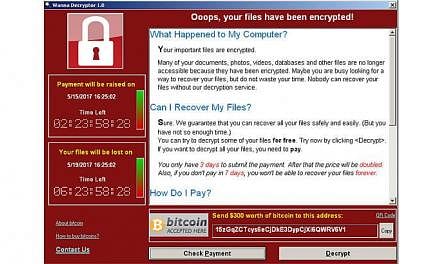

Europe and Asia were the regions most affected by the crime, with hospitals, car plants and even the Russian Ministry of Interior falling prey to the malware, which takes over a computer, locks down the machine and releases it only when the owner has paid a ransom.

Hours after the attack was first reported in Britain, where the computer systems of the National Health Service were crippled, law enforcement agencies across Europe, Asia and the United States began looking for clues that could trace the assault to specific people or organisations.

As with a physical crime scene, the first step with any cyber investigation is to make sure the criminal is no longer hiding out, about to pounce again.

"Before we get into who did it, we try to figure out if the bad guys still have access," said Ms Theresa Payton, a former chief information officer of the White House and founder of Fortalice, a cyber security firm.

"Are they still hiding? Are they going to come back tomorrow? Is the door that let them in still ajar? Can they inflict more pain?

"And if so, where are they?" she added. "How do we cordon them off to mitigate further damages?"

Instead of searching the closets of a property that has been broken into, investigators will examine the affected server, online software caches and e-mails to identify any malware that might not have been activated yet.

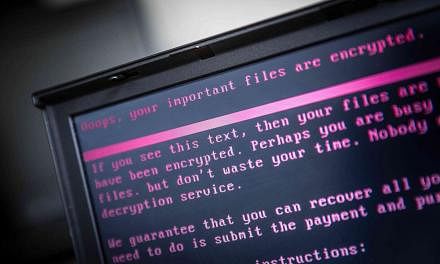

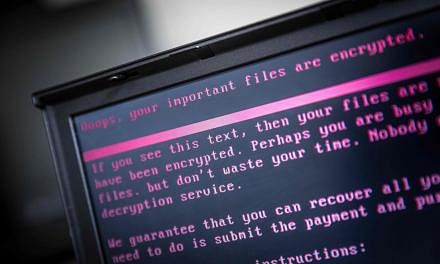

In the case of the ransomware that was unleashed on Friday and is known as WannaCry, Wcry or Wanna Decryptor, it was quickly determined that updating Windows software with the latest security patch was enough to inoculate computers that had not been infected.

Then the forensic work begins, with agents looking for digital fingerprints.

Because of the highly technical nature of these investigations, private data security teams can be expected to help in the search. That includes working directly with law enforcement to uncover clues left behind by the attackers, as well as tracking the virus and its effects separately to protect their corporate clients.

In the WannaCry case, the phishing e-mails sent by the criminals with the infected link are a key piece of evidence.

Ms Patricia Lewis, international security research director at Chatham House in London, likened the text of the e-mail to a physical letter and its metadata to the envelope it arrives in.

"An envelope has lots of information on it: the stamp with the time and place it was sent from, the handwriting or printer type, a sender's address, maybe a fingerprint or DNA from saliva on the seal," Ms Lewis said.

Criminals are aware their e-mails contain revealing clues, and they try to cover their tracks. "People use cloakers, which hide your identity, making you look as if you are someone and somewhere else," she said.

Like tracing the licence plates of a stolen car back to the wrong person, this can lead investigators astray. "But a good detective can track them," Ms Lewis said. "They always leave digital breadcrumbs that can be followed."

Investigators will check whether the e-mail address the malware came from is linked to social media accounts, past cybercrimes or other locations on the web. They will study the domain name it is linked to. And they will look for patterns to try to connect one crime to others.

Success often depends on whether law enforcement can tie small digital details, including potential mistakes or a certain style in the programming code, back to the criminals. The location of where some of the ransom money is withdrawn can also help connect the dots.

Sometimes the patterns that lead investigators to their target can be surprising. One state-sponsored hack was traced to Russia because detectives noticed those responsible were online only from 9am to 5pm Moscow time, Ms Lewis recalled. In another case, hackers were observing Chinese holidays.

When Sony was hacked, officials linked the malware that was used to one that had been used before in North Korea.

"That was a big clue," Ms Lewis said. "But of course it could have been deliberately planted."

In the recent hack of the political campaign of the new president of France, Mr Emmanuel Macron, for instance, security experts were able to link the registration of certain website domains used in the attack to Russian hackers.

Investigators in the latest attack are looking for clues in the ransom notes written in more than 20 languages. Some suggested that the assailants might have connections to China because the Mandarin version of the text was better written than its English equivalent.

Once equipped with enough identifying data to start narrowing down suspects, investigators will go undercover to listen to the chatter on technology boards where cyber criminals are known to spend time.

"It's like using an undercover operative purporting to be part of a criminal gang, except it's online," Mr Inkster said.

"Half the dark web are cyber agents these days," Ms Lewis joked. "They're tripping over each other."

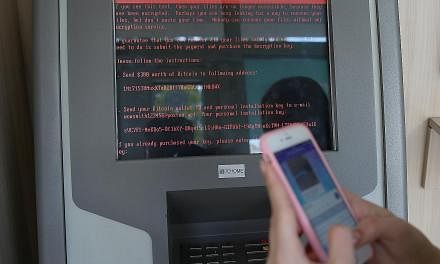

One of the most challenging new developments for investigators is the use of bitcoin, a digital currency with little oversight.

In the latest attack, the criminals demanded ransoms ranging from US$300 (S$422) to US$600, to be paid in bitcoins.

Bitcoin accounts, or wallets, are extremely difficult to trace. While law enforcement agencies have cracked cases by tracking bitcoin transactions, the process is arduous and expensive.

It could take months, if not years, for law enforcement agencies to pinpoint the identity of the attackers.

Ultimately, in the world of computers, as in the physical world, investigators rely on criminals to make a mistake.

As Mr Adam Malone, a former cyberagent for the FBI, put it: "A lot of times we catch bad guys because they get sloppy."