Marathon United Nations climate talks went deep into overtime yesterday as negotiators tried to overcome differences on a deal meant to drive greater efforts to limit the threat from increasingly extreme weather.

Exhausted negotiators from nearly 200 nations were expected to agree to the deal early today, Singapore time, after the meeting in Katowice, Poland, went more than 24 hours beyond a Friday deadline.

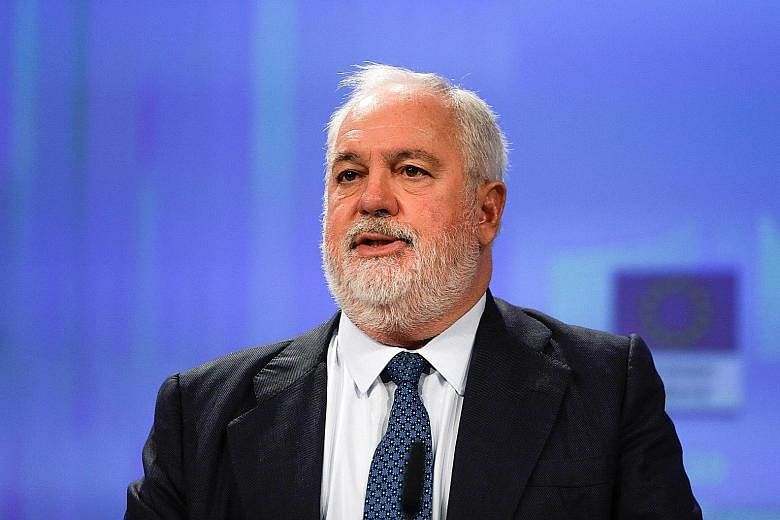

European climate commissioner Miguel Arias Canete tweeted yesterday: "UN climate talks go into overtime. Latest version of the draft agreement just out... A deal to make the Paris Agreement operational is within reach."

Delegates at the two-week talks, called COP24, were tasked with completing a complex rule book that would allow the 2015 Paris climate agreement to go into action in 2020.

The Paris deal was hailed as a landmark because, for the first time, it committed all nations to making cuts to planet-warming greenhouse gases based on their capabilities, with the goal of limiting global warming to less than 2 deg C and ideally 1.5 deg C.

Under the Paris Agreement, national climate action plans are meant to be regularly strengthened to ensure emissions cuts accelerate over time, and those plans are also meant to be periodically reviewed and scrutinised to ensure no backsliding.

But working out the rules putting these goals into practice has taken a further three years of talks - right at a time of rising popularism, threats to multilateralism and United States President Donald Trump's decision to pull out of the Paris pact, though that will take several years to take effect under UN rules.

The UN and many poorer, vulnerable nations appealed for a strong rule book that would boost global ambition in cutting emissions, saying ever more severe weather and rising sea levels were pushing their economies to the brink.

Yesterday, the final plenary session was repeatedly delayed as negotiators spent the day haggling over contentious areas.

A major sticking point - about how carbon emissions should be accounted for - was blamed for holding up the talks and there were suggestions that part of the agreement would be held over for further negotiations next year.

The crux is whether developing countries should be allowed to "double count" their credits for tradable emission reductions - those that can be traded with other nations to help them meet their emission reduction targets.

The Paris Agreement provides for a new kind of tradable offsets known as Internationally Transferred Mitigation Outcomes. This means that once a country sells the credit to another country, it should be retired from the seller's inventory, and not used to offset the seller's emissions.

But Brazil wants developing countries to be granted a grace period that will allow them to do both - sell the credits, and also use the sold credits to count towards their emissions reduction, with the caveat that they will make adjustments at a later date.

Many countries objected to this, saying it would undermine the global ambition to cut emissions.

"There are still a range of possible outcomes and Brazil continues to work constructively with other parties to find a workable pathway forward," Brazil's chief negotiator Antonio Marcondes told Reuters.

Other parts of the 156-page draft looked to be in better shape, including the key area of transparency.

Under the current UN framework, developed and developing countries have different transparency mechanisms for the measurement, reporting and verification of national climate pledges.

The rule book includes the new Enhanced Transparency Framework, which would from 2024 subject all parties to the same reporting, measurement and verification standards. However, developing countries will get the necessary support to do so, in terms of finance and capacity-building, for example.

Such a framework will also provide the basis for countries to ramp up their pledges every five years.