Britain has stunned the world and its European partners with its decision to walk out of the European Union, setting off shock waves globally.

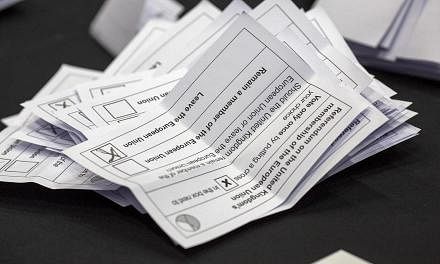

After a bruising 10-week referendum campaign marred by vicious personal attacks, crude appeals to nationalist and racist sentiments and widespread, blatant twisting of facts by all sides to the debate, the Leave camp won with 52 per cent of votes and the Remain camp 48 per cent in a tightly fought race.

This not only represents a leap into the unknown for Britain, but also for Europe as a whole, where populists of every stripe and nation are guaranteed to demand similar referendum votes in their own countries.

The entire European Union project is now under serious threat, and averting its unravelling will preoccupy the continent's leaders for many years to come.

After the official results were out on Friday (June 24), Prime Minister David Cameron, who led efforts to get Britain to remain in the EU, announced that he would resign by October.

Mr Cameron is already facing a stock market meltdown and a nosediving national currency, and although both the Bank of England and government regulators have plans to shore up the country's critical economic infrastructure, it will be some time before financial markets regain their poise, especially since the main question for banks and investors now is whether Britain will be able to maintain its status as Europe's pre-eminent financial centre once the country is out of the EU.

Paris and Frankfurt, London's historic rivals, may now seize an opportunity to take its spot.

Mr Cameron - who will likely remain as prime minister in a caretaker capacity for a number of months - is guaranteed an icy reception when he meets his EU counterparts at a summit next week. EU leaders have always been irritated by Mr Cameron's decision to hold a referendum, a move which they regarded as both reckless and unnecessary. They will feel vindicated, and will blame Mr Cameron for the continent's predicament.

But cooler heads are likely to prevail. The last thing Europe needs now is a public spat with Britain, which may spark off a continent-wide rout for financial markets and spook international investors even further.

The process of separation is also likely to take around two years and so it may suit all EU governments to tone down their immediate grandstanding.

But events are likely to spin fast and beyond anyone's control. Populists and extreme nationalists in Europe are bound to demand similar referendums in other European countries: demands from France and Italy are already audible. Europe's "divorce" negotiations with Britain will therefore have to run against the backdrop of domestic pressures in many EU countries.

And as Mr Cameron will discover during the emergency parliamentary sessions in London early next week, the British government will struggle to get the necessary mandate it needs for the launch of the separation negotiations with the rest of the EU.

All anti-European MPs, a majority of whom belong to Mr Cameron's Conservatives, will want the government to impose immediate border controls and restrictions of immigrants; they will claim that doing anything less would pervert the expressed wish of the electorate.

But Mr Cameron cannot afford to give in to such demands; he would wish to appear to be respecting EU regulations throughout the period of the separation negotiations, and that means keeping Britain's borders open to EU nationals, however unpopular that may be.

Yet in order to hold the anti-EU lawmakers at bay, Mr Cameron would need the support of the opposition Labour. And that's a tall order as the opposition's main task now is to make the government's life unbearable in the hope that this would precipitate early general elections.

The result could well be that Britain will be gripped by political paralysis, as its prime minister struggles to even get a national mandate for the negotiations with the EU, while EU leaders demand quick answers from London.

To complicate matters further, Nato, the US-led military alliance in Europe, is also due to hold its summit in early July, where Mr Cameron will face US President Barack Obama, who has publicly urged the people of Britain to remain the EU.

Mr Obama is unlikely to take the rebuff of the British electorate personally. But the US administration is guaranteed to ask itself some searching questions about the utility of Britain as a military ally outside the EU. And a Nato summit which is supposed to be devoted to discussing the crisis in Ukraine and the tense relations between the West and Russia will be concerned instead with just maintaining a semblance of unity among the allies .

In the months to come, the people of Britain will discover that a multitude of rights they took for granted - from the freedom to travel, work or settle anywhere in Europe to the ability to buy property and save for their retirement - will suddenly appear less secure.

But that's the inevitable consequence of tearing apart arrangements which governed Britain's relations with the rest of Europe for the past half century.

Those who supported Britain's departure from the EU had dismissed warnings from experts that this is likely to prove a costly proposition. Now they will discover that the bills will pile up, and far quicker than anyone anticipated.