NEW YORK • Scientists have been warning for decades that climate change was a threat to the immense tracts of forest that ring the Northern Hemisphere, with rising temperatures, drying trees and earlier melting of snow contributing to a growing number of wildfires.

The ravaging of a Canadian city last week by a fire that sent almost 90,000 people fleeing for their lives is grim proof that the threat to these vast stands of spruce and other resinous trees, collectively known as the boreal forest, is real. And scientists say a large-scale loss of the forest could have a profound impact on efforts to limit the damage from climate change by soaking up greenhouse gas emissions.

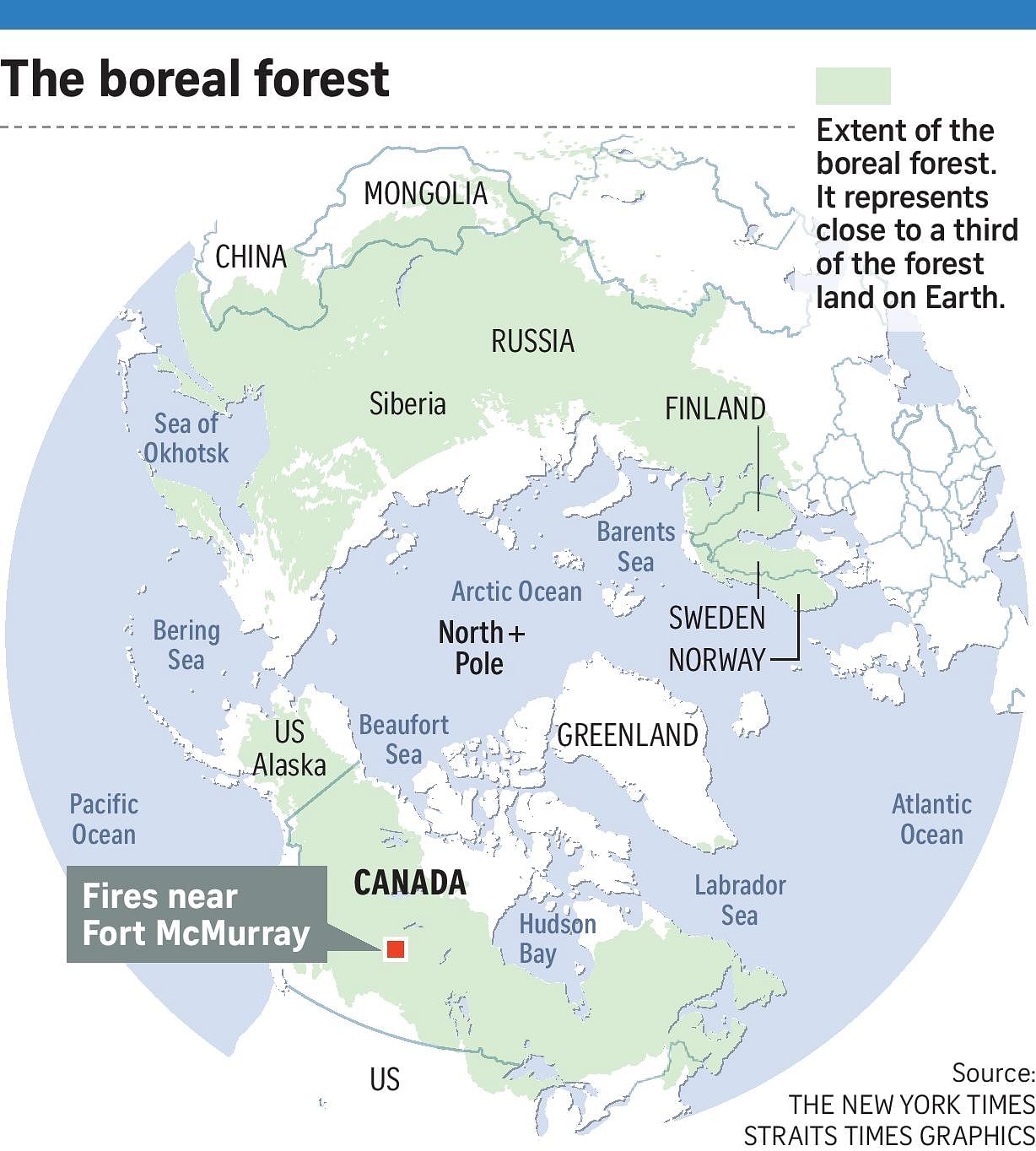

Scientists have been trying for years to call attention to the boreal forest. (Boreal essentially means northern.) The forest gets less public focus than tropical forests, but it represents close to a third of the forest land on the planet. It is ecologically unique, and vital to human welfare for its ability to limit the risks of global warming.

The boreal forest consists mainly of cone-bearing trees like pines, spruces and larches, adapted to survive the long, cold winters of the northern region. The forest encircles the Northern Hemisphere in a band near and just below the Arctic Circle, through Alaska, Canada, Scandinavia and Russia.

In retrospect, it is clear that Fort McMurray, in northern Alberta, was particularly vulnerable as one of the largest human outposts in the boreal forest. But the destruction of patches of this forest by fire, as well as invasions by insects surviving warmer winters, has occurred across the hemisphere.

In Russia, about 28 million ha burned in 2012, new statistics suggest, much of that in isolated areas of Siberia. Alaska, home to most of the boreal forest in the US, had its second-largest fire season on record last year, with 768 fires burning more than two million ha.

Global warming is suspected as a prime culprit in the rise of these fires. The warming is hitting northern regions especially hard: Temperatures are climbing faster there than for the Earth as a whole, snow cover is melting prematurely, and forests are drying out earlier than before. The excess heat may be causing more lightning, which sets off devastating wildfires.

"It's clear the warming temperatures and extraordinary drought are major players here," said Professor Thomas Swetnam, an emeritus scientist at the University of Arizona who studies the ecology and history of wildfire.

The weather pattern known as El Nino has been pumping a huge amount of heat from the ocean and into the atmosphere for more than a year, and scientists say that could have played a role in setting the conditions for this year's fires.

Yet the same scientists say the overall increase in fire in northern regions would not be happening without global warming, predicted decades ago as one of the likely consequences of human emissions.

The situation, experts said, demands new thinking by governments about how to manage forests and protect nearby human settlements. Fort McMurray, for instance, has just a single road in and out of the city. But the dangers go far beyond the risk to communities on the front lines.

The forests of the world are helping to offset rising human emissions of greenhouse gases, absorbing a significant portion of the carbon dioxide that the burning of fossil fuels throws into the air. So far, even as fires and other disturbances increase, the forests are growing more than enough to compensate.

But scientists see a risk that if the destruction from fires and insects keeps rising, the situation will reverse, and some of the carbon that has been locked away in the forests will return to the atmosphere as carbon dioxide, accelerating the pace of global warming and further magnifying the stress on the forests - a dangerous feedback loop.

In addition, winds are sometimes carrying soot from the northern fires onto the immense sheet of ice covering Greenland, darkening the surface and causing it to absorb more of the sun's heat.

Experts fear more fires, and more soot, could further accelerate the melting of the ice sheet, which has the potential - should it all disintegrate - to raise the global sea level by more than 6m.

NEW YORK TIMES