LE BOURGET (France) • After the stomping and cheering died down, a question hung in the air as the climate conference came to a close: What does the new deal really mean for the future of the earth?

Scientists who closely monitored the talks said it was not the agreement that humanity really needed. By itself, it will not save the planet.

The great ice sheets remain imperilled, the oceans are still rising, forests and reefs are under stress, people are dying by the tens of thousands in heatwaves and floods, and the agriculture system that feeds seven billion human beings is still at risk.

Yet 50 years after the first warning about global warming was put on the desk of a US president and quickly forgotten, the world political system is finally responding in a way that scientists see as commensurate with the scale of the threat.

"I think this Paris outcome is going to change the world," said Dr Christopher Field, a leading US climate scientist. "We didn't solve the problem but we laid the foundation."

The agreement reached last Saturday will, if faithfully carried out, achieve far larger cuts in emissions than any previous climate accord. It will reduce the risk that runaway climate change may render parts of the earth uninhabitable.

The deal, in short, begins to move the countries of the world in a shared direction that is potentially compatible with maintaining a liveable planet over the long term.

Perhaps the most important part of the deal is that it explicitly recognises that countries were not ambitious enough in the emission cuts that they pledged ahead of the Paris negotiations, pledges that were incorporated into the document. The agreement, in effect, criticises itself for not doing enough.

To compensate, the deal sets up a schedule of regular review that will encourage countries to raise their goals over time. It envisions a tighter system to monitor whether the nations are keeping their promises - though how tough that will really be was put off to future debates.

In interviews, scientists with long experience studying climate change said they were heartened by the cooperative tone in Paris.

But for the deal to mean anything, they said, the celebratory moment must give way immediately to an era in which intensive efforts are made to squeeze emissions out of the world economy.

That task will fall largely to businesses and investors, operating under emission-reduction policies that countries have pledged to put into effect by 2020.

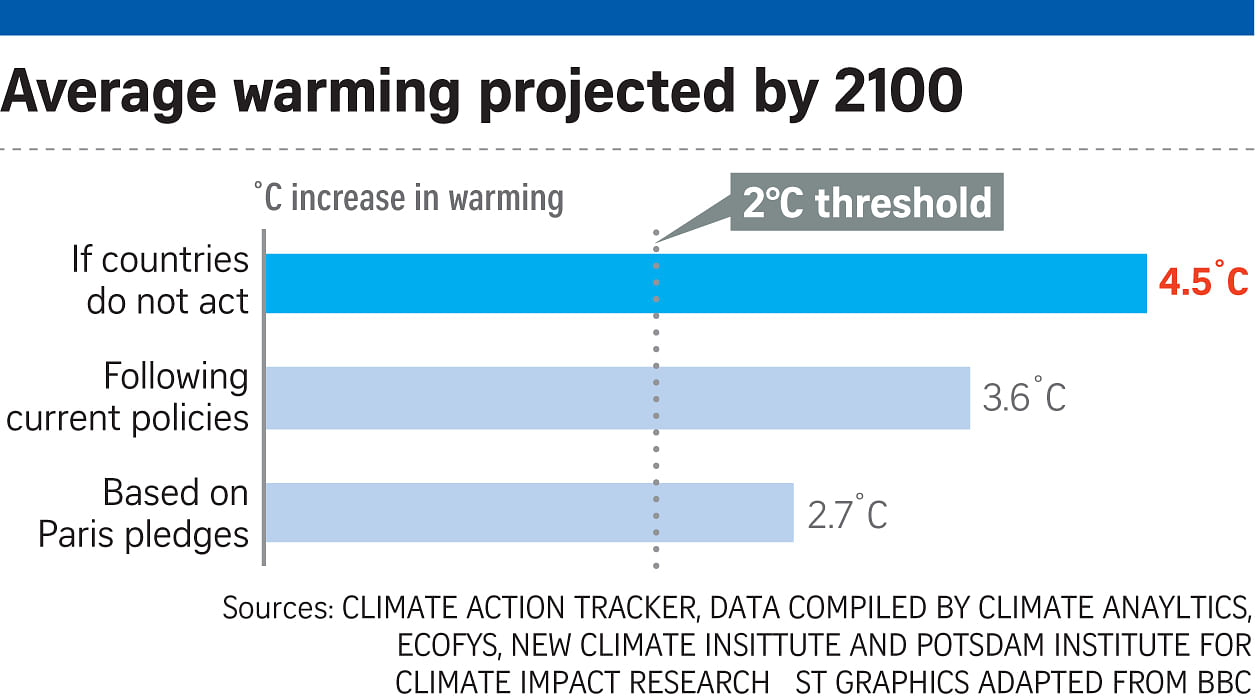

Since a 2010 agreement in Cancun, Mexico, the official goal of international climate policy has been to limit the warming of the earth to 2 deg C above the level that prevailed before the Industrial Revolution.

The Paris deal sets a more ambitious target, declaring that the global average temperature ought be kept "well below" 2 deg C, and that countries should try to go further, limiting warming to 1.5 deg C.

Experts hope that, by highlighting the gulf between humanity's stated goals and its plans to achieve them, the Paris deal will launch a more intensive push to figure out how it might actually be done.

"We lost a lot of time that could have been used trying out innovative solutions. Now, we have a lot of experimentation still to do," Dr Field said.

NEW YORK TIMES