A video ad by the National Environment Agency (NEA) on reducing food waste showed up earlier this year - on a website carrying articles that support the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria.

Similarly, the ads of many local household brands - including retailer chains, banks, airlines and telcos - have popped up unwittingly on other incendiary websites, including one with content from preachers linked to terrorism.

Advertisers were aghast at the prospect of a public relations nightmare when contacted by The Straits Times in February. They were unaware that their ads were showing up on these sites.

The ads have since been taken down, but were a wake-up call to Singaporean advertisers and consumers about the pitfalls of digital advertising. Such incidents are shining the spotlight on a new level of automation and sophistication in ad management: a process called programmatic advertising, which is capable of reaching millions of people instantly.

Where once an ad was put in a newspaper or on TV or radio and shown to a mass audience, now computer programs pinpoint the exact viewer based on his Web-surfing habits and put up ads that match his interests.

But despite the promise of digital ads being more effective because they can target a market so precisely, the downsides include a target reach that is totally fake or wrongly identified.

In the case of the fakes, ads might be clicked on but not actually viewed, yet still counted as so, or increasingly, not even being seen by a human being. They are mass-clicked by robots, or bots, programmed to mimic how humans browse the Internet.

In the NEA case, ads can also show up unwittingly on dubious websites.

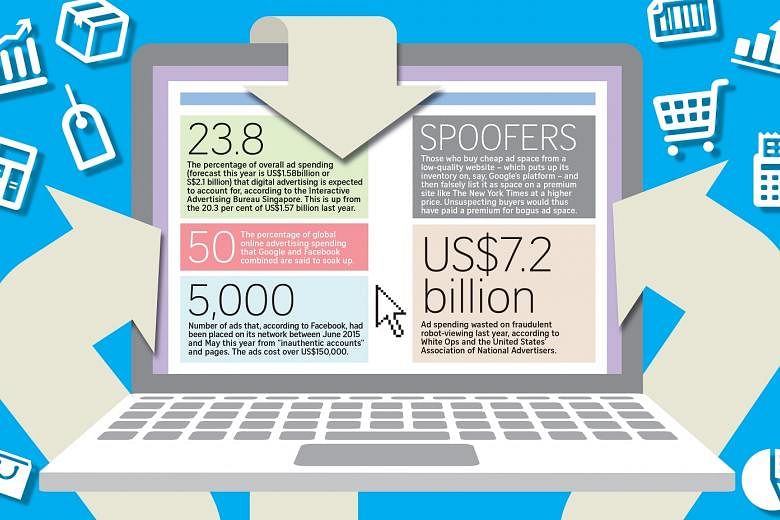

Yet digital advertising offers huge potential. To see how it is clicking with advertisers, take these figures: The Interactive Advertising Bureau Singapore expects digital advertising to account for 23.8 per cent of the overall ad spending of US$1.58 billion (S$2.1 billion) forecast for this year in Singapore - up from 20.3 per cent of US$1.57 billion last year.

The absence of an independent auditing body in Singapore to tackle the scourge of fake online ads and hold entities like Facebook and Google accountable means the job of policing rests on the shoulders of advertisers and their appointed media agencies.

So the challenge is to better harness the potential of digital advertising, while stamping out the problems. What is being done and what lies ahead?

PROMISE OF DIGITAL ADS

With digital advertising, marketers can specify the viewers they want their digital ads to be shown to. For instance, Nestle could target people interested in baby products in Singapore and Malaysia.

Google and Facebook - combined, they are said to soak up about 50 per cent of global online advertising spending - are able to allow such targeting as they have a detailed profile of almost every Internet user on the planet. The profiles have been built up over time using "cookies" - computer programs embedded in the Web browser or smartphone app - to track people's location and surfing patterns.

Digital advertising also offers marketers a more precise measurement of the success of their campaigns. This is done using metrics such as page views and click-throughs. The former logs the number of times someone is looking at a webpage where an ad sits, while the latter refers to the number of times people click on an ad.

The higher the number of page views or click-throughs to elicit some sort of action, be it to buy a book or watch a video, the more effective - supposedly - the marketing campaign.

FAKE TRAFFIC

However, fraudsters have abused the system with fake ad views and so these metrics have lost their value, causing advertisers to rethink how they spend their brand dollar.

A report in May by ad-fraud detection intelligence firm White Ops revealed that robots, or fake viewers, are solely responsible for the user traffic of one in five websites, inflating page views artificially to generate revenue for the sites' creators.

Some of these websites with inflated page views turn a blind eye to the fake traffic, while others are created by cyber criminals selling bogus ad space. Bots can reside on Internet users' computers via malware embedded in ads.

In July, consumer goods giant Procter & Gamble (P&G) became the latest global retailer to reduce online advertising.

It cut US$140 million in digital ad spending in the second quarter, with finance chief Jon Moeller saying this was prompted by fake traffic driven by bots. P&G said the move had little impact on its business and proved that some online advertising was largely ineffective.

Mr Michael Tiffany, co-founder and president of White Ops told Insight: "Clicks are no longer a good success metric for digital advertising. No one loves clicking on ads quite so much as bots."

Some US$7.2 billion in ad spending was wasted on such fraudulent robot-viewing last year, said White Ops and the United States' Association of National Advertisers (ANA). This is based on a study of 49 ANA members' digital advertising activity between October last year and January. "Cybercrime is global, and digital advertising is global. No market, including Singapore, is immune to ad fraud," said Mr Tiffany.

DUBIOUS WEBSITES

The high level of automation across the digital ad supply chain has created uncertainties in many ways.

First, ad placement at such a high speed and large scale has made it hard for brands to know exactly where their campaigns are appearing. It does not help that any publisher, including unsavoury ones, can list their ad inventory on the Google platform, which is accessed by advertisers and their media agencies.

Advertisers can pick specific sites to place their ads although some media agencies are not aware of this feature and many would rather negotiate with publishers directly. Advertisers can also block their ads from showing up on specific sites.

Not only have the ads of Singapore household names shown up unwittingly on incendiary websites, The Times in Britain reported in February that global brands, including Mercedes-Benz and British charity Marie Curie, had been placed alongside sites promoting extremist or pornographic content.

Then there is the problem of fake news peddlers who, for example, generated tons of pro-Donald Trump news during the US presidential campaign. The fake reports were the most-shared and most-read items and this allowed the culprits to soak up a sizeable amount of advertising dollars via intermediaries like Google.

Mr Benjamin Ang, president of the Internet Society (Singapore), a non-profit organisation, said the problem stems from a lack of transparency in knowing just who or what the audience actually comprises, such as the proportion of online ads that are viewed by robots. There is also little information on whether ads are appearing on undesirable or fake websites.

"The real figures are known only to platforms like Google and Facebook, which is part of what has led to this problem," said Mr Ang.

Independent marketing consultant Ian McKee agrees. He said: "Programmatic advertising started as a black box; advertisers were blind as to where their ads were showing and to whom. But now, sophisticated marketers want a disclosed model where they get full transparency on costs, fees and traffic."

NEED TO RESTORE CREDIBILITY

Efforts have been made to restore credibility to the platform.

In the name of transparency, Facebook disclosed last week that more than 5,000 ads, costing over US$150,000, had been placed on its network between June 2015 and May this year from "inauthentic accounts" and pages, likely from Russia. Facebook declined to reveal more, but said it had given the information to the US authorities investigating Russian interference in the US election last year.

Google, on its part, is issuing refunds for ads that ran on websites with fake traffic, the Wall Street Journal (WSJ) reported last month.

Citing ad buyers, the WSJ reported that refund amounts range from "less money than you would spend on a sandwich" to hundreds of thousands of dollars.

When contacted, a Google spokesman in Singapore declined to disclose the proportion of ad fraud in Singapore, noting that "the vast majority" of fake traffic has been filtered out internally before advertisers make a bid on an ad space on its platform. It is also blocking payments to publishers if invalid traffic is involved.

Plus, it is working with US trade body Interactive Advertising Bureau to spot counterfeit ads using a tool called Ads.txt, which lets publishers insert a text file into their Web servers to list the authorised middlemen that sell their ad inventory, to weed out "spoofing".

Spoofers buy cheap ad space from a low-quality website - which put up its inventory on, say, Google's platform - and then falsely list it as space on a premium site like The New York Times at a higher price. Unsuspecting buyers would thus have paid a premium for bogus ad space.

Another initiative is spearheaded by audience measurement services firm Comscore. It will be launching a free tool, dubbed Viewability, by the end of this month to help advertisers track whether their ads are viewed by robots. Advertisers just need to insert a Javascript computing code into their ad for the measurement tool to do its tracking and reporting.

The tool can also determine if at least half of an ad appears on a browser's viewable portion for at least one second - to help marketers decide if effective viewing has taken place.

The problem now is that even if the ad takes up a few pixels in the most obscure portion of the Web browser, it will still be registered as a page view - with advertisers charged unfairly for it.

Experts laud such efforts to ensure transparency in measuring how efficient or effective an ad is.

Ms Miranda Dimopoulos, chief executive of Interactive Advertising Bureau Singapore, said: "It is a reflection of a market that is rapidly maturing and executing a more nuanced understanding of the digital landscape."

In the absence of an independent auditing body, advertisers would have to do most of the heavy lifting themselves.

Said Professor Ang Peng Hwa, legal adviser to the Advertising Standards Authority of Singapore (Asas): "Advertisers should (establish) the efficacy of digital advertising. This is not just a statistical issue but also of perception such as being associated with fake news sites."

Asas, an advisory council under the Consumers Association of Singapore, promotes ethical advertising practices but does not do auditing work.

Dr Adrian Yeow, senior lecturer at SIM University's School of Business, said the assurance of audience quality is best obtained directly from publishers and not via programmatic exchanges or intermediaries. "Marketers need to continually monitor their buys to understand what works and what doesn't. Like investment portfolios, advertisers need to decide how they want to put their budget into which bucket," he said.

To prevent future occurrences such as the NEA ad showing up at inappropriate sites, a Ministry of Communications and Information spokesman said government agencies have since put in place "safeguards such as brand safety filters".

These filters ensure that government advertisements are not associated with websites and keywords associated with violence or profanity, for instance.

The spokesman added: "Nevertheless, should such advertisements be wrongly served, we will take it up with media-buying agencies and platform owners such as Google, and work together to remove these advertisements."

Correction note: This story has been edited for clarity