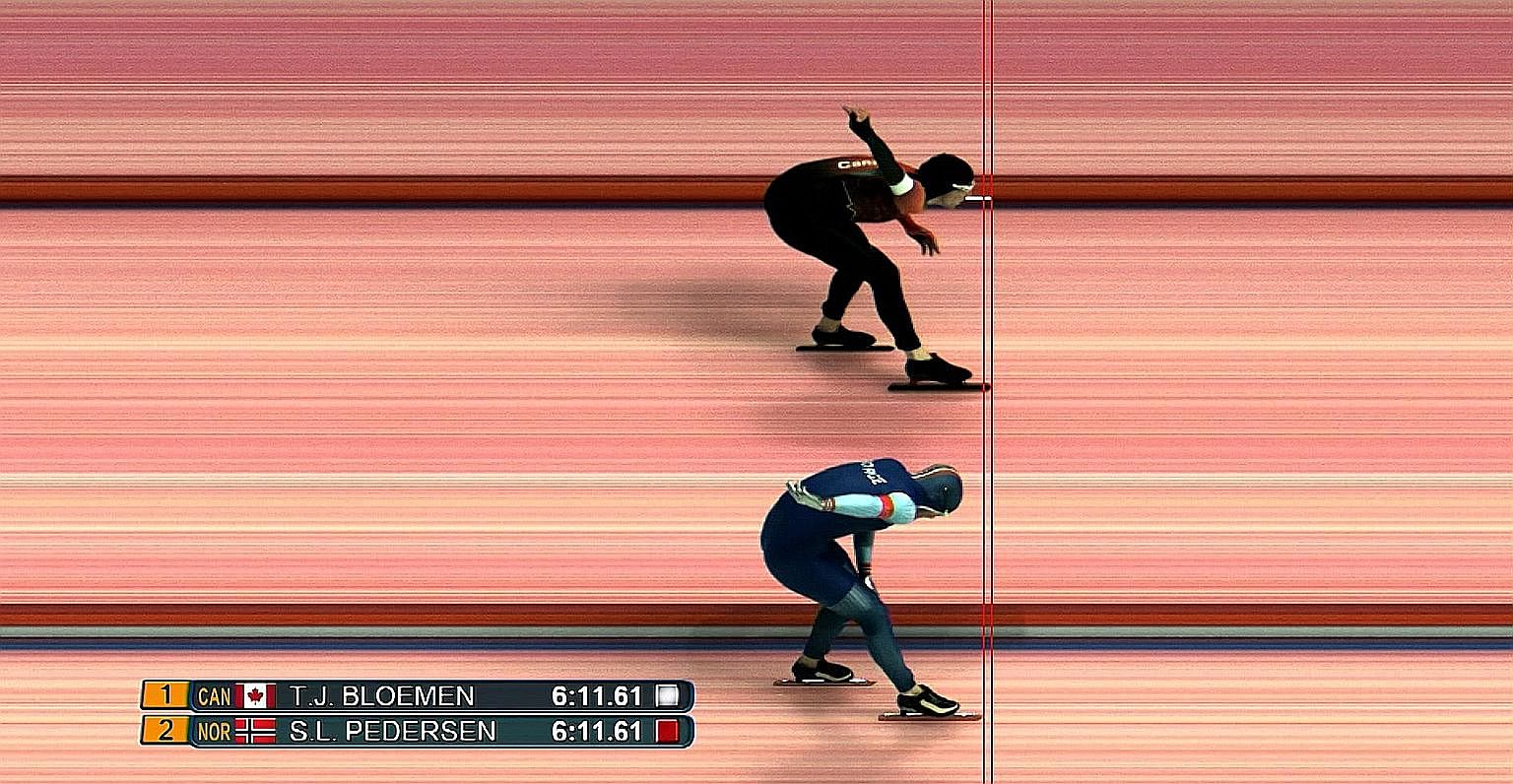

"This is sport," says Jasmine Ser, the shooter, when I tell her about the photo. It's a photo of brutality and beauty. A photo that represents the lunatic margins that decide athletic lives. A photo from the men's 5,000m speed skating last Sunday at the Winter Olympics of Ted-Jan Bloemen and Sverre Lunde Pedersen at the finish.

After years of training and suffering, after thousands of kilometres skated, this is what separates Pedersen bronze from Bloemen silver:

.002 of a second.

Heartbreak in a blink. Failure by a capillary.

Exhausted, defeated, does the athlete ask: Could I have gone faster? Could I have done something better? Anything? Is defeat by a centimetre somehow worse than a loss by a metre?

Either way as the cameras stare at him, the athlete finds equanimity. Says Pedersen: "It was a little pity that he beat me by I don't know how many thousandths (of a second), but at the end I'm very happy for the medal." He had never won one before.

These days talent is separated by an Omega photo-finish camera which takes 10,000 digital images per second. In older times, back in 1932, judges watched black-and-white film and made a decision.

In the Olympics that year, Ralph Metcalfe and Eddie Tolan both timed 10.3 seconds in the 100m. Even though some thought Metcalfe had won, after several hours Tolan was awarded the gold. In a documentary on the Olympic Channel, Lindy Remigino, who also won the 100m gold in a photo finish in 1952, said Metcalfe never accepted that defeat all his life. "He said, 'I won that race'."

If no one else remembers the margin of defeat, then the athlete never forgets. Yet even as such a loss can be wounding, athletes are often stoics who learn to wear defeat philosophically, who use pain as provocation, who spin heartbreak into a positive lesson, who push away the "what ifs" and tell themselves: I was close. Almost there. On the right track.

Last year Ser is ninth in the qualification in the 10m air rifle at the Munich World Cup which has a tough field. Ninth when only eight qualify. Ninth by .1 of a point. Ninth by a distance almost no greater than the thickness of the human skin.

Ser feels briefly bitter, she thinks "Oh so close", but she uses it as an education: "This is what sport teaches us, to be tougher and come back tougher." Athletes, if they want, can convince themselves of anything and she decides that missing the finals was better than making the finals. "It makes you want to try harder next time."

A shot putter once lost Olympic gold by half an inch. A swimmer was denied Olympic gold by .01 of a second. Athletes will rewind a videotape a hundred times, but in every viewing they will still lose. In the 2013 SEA Games, sprinter Shanti Pereira comes fourth in the 200m by .03 of a second. It hurt, she says. "You never get used to it," she adds.

But, like Ser, she considered it a schooling, as if this made her more literate in the athletic arts. "It teaches you that every race you really need to fight," she says. All that stuff your coaches said about giving your best all the time, all those overused lines about focus from start to finish, it wasn't a joke. It was for this. For the .03.

Sometimes, of course, an athlete can't offer any more, everything is given, nothing is left. Sometimes they can be relieved and frustrated all at once, which is what happens to Roanne Ho at the World Cup last year when she breaks the national record in the 50m breaststroke yet comes fourth by 0.17sec.

Sometimes in the small margin of defeat is also found a great dignity which is more profound than the colour of any medal. At the 1988 Seoul Olympics, Grant Davies celebrates when the scoreboard states that he has won a tight race in the K1 1,000m and then 10 minutes later he's told he has lost by a centimetre.

Sulk? No. Tantrum? No.

Instead he says: "If that's the biggest disappointment in my life, I've got no problems."

Athletes keep going because one day they believe they will be the other guy, who is better by a fingernail and ahead by an eyelash. Bloemen, who wins silver, doesn't have his best race but he finds something in himself. "I was having trouble in the second part of the race so in the last two laps I give it everything ... In the last corner I could hardly stand."

Sometimes you just find that extra burst of energy, a last surge, a final push, like Muhammad Ali did at the end of rounds. "You squeeze out just a little more," says Stephenie Chen, the kayaker who can still remember losing silver at the 2016 Asia Open Canoe Sprint Cup by .052 of a second. "That's the beauty of it, how you never ever give up because you never know what can happen. Sport can be very, very painful but it has its rewards.

"That's what you're in it for."

For the chance. And for the chase.