It is only fitting that when Cannibals, Assassins, Hulks, Godzillas and Natural Born Killers come together, their meeting is held in a cage. If you are wondering what precisely is going on, these are the rather alarming nicknames of mixed martial arts fighters. Nothing here is as subtle as the men's rugby team from Japan, who are known as the Brave Blossoms. Which, respectfully, is an improvement on their earlier nickname, the Cherry Blossoms.

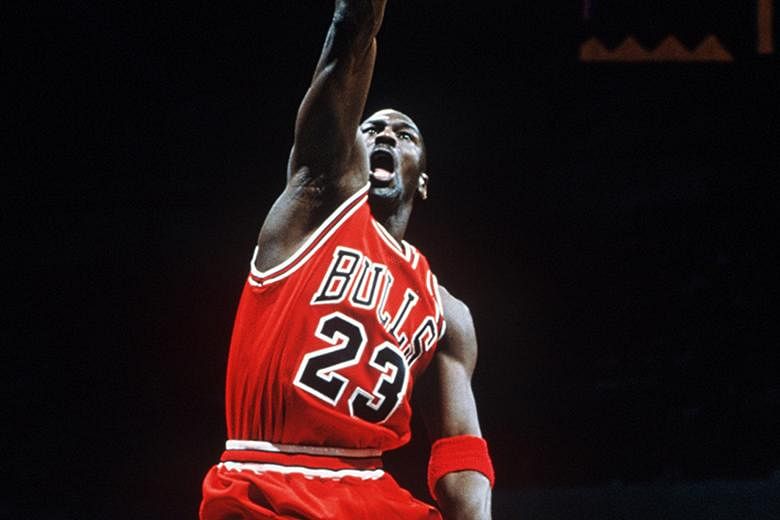

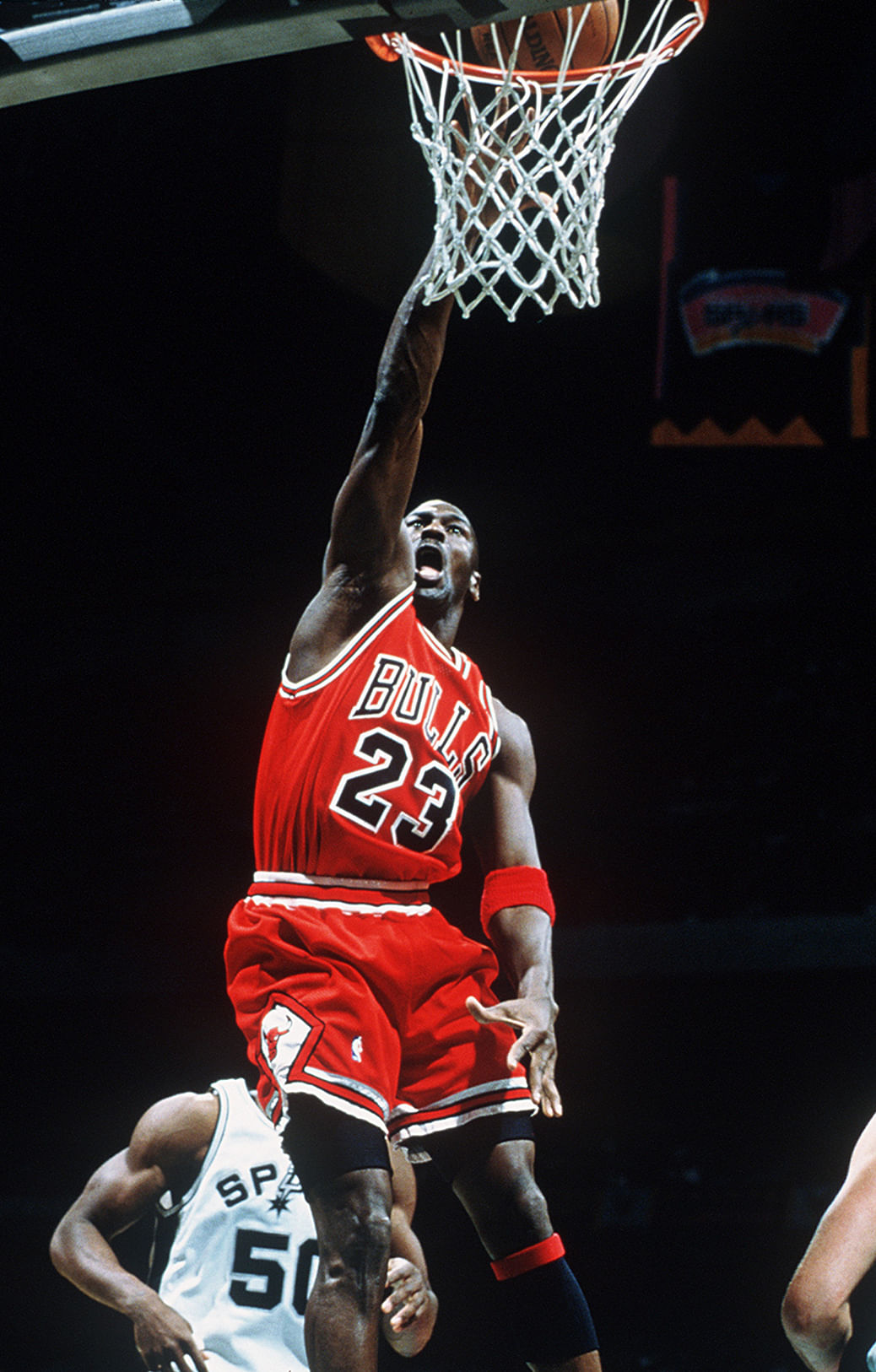

I don't much care for team songs and have never met a mascot that wasn't deeply annoying. But I'm a sucker for nicknames because they can have style, heft and charisma. Like "Magic" Johnson, whose mother didn't like his nickname but a young Michael Jordan did. In his book Michael Jordan: The Life, Roland Lazenby wrote that Jordan's girlfriend actually bought him a vanity plate for his car which read MAGIC MIKE. In time, that nickname disappeared into thin Air.

Nicknames are on my mind because of the death of the brilliant racer John Surtees, who was known in Italy as "figlio del vento". Son of the Wind. Poetic and evocative. Yet not as scary as the label attached to the three-time Olympic wrestling champion Alexander Karelin, who was 130kg and once carried a fridge up eight stories to his flat: He was simply called The Experiment.

Nicknames gave athletes a flavour and personality, they carried humour and hubris and helped to informally bond the athlete with the fan.

They were a type of branding before anyone had heard of branding. They could be clever - baseballer Buck Fausett was known as Leaky - or paint a graphic picture which was the case with the chugging long-distance runner Emil Zatopek who was dubbed The Czech Locomotive.

Boxers, above all, seemed to fit into their nicknames, as if their monikers were an advertisement of their style. So Thomas Hearns was The Hitman and Argentina's Luis Firpo was the Wild Bull of the Pampas. Often these names came from sports writers or stadium announcers, but sometimes boxers found nicknames for themselves. Like that fellow did, you know The Greatest?

These sobriquets - most popular in America - helped to build the mythology of the hero but also had a utility value. They allowed us to turn our beloved but long-winded Brazilians into easy four-letter words. So Edson Arantes do Nascimento became Pele, Arthur Antunes Coimbra was Zico and Edvaldo Jizidio Neto was turned into Vava.

Attempting to be inventive with nicknames is a nightmare for so much ground has been covered before. Stan the Man isn't a Wawrinka original but in fact belongs to Stan Musial, who played baseball from the 1940s-60s. Nickname writers are also clearly intoxicated by flight for we have the Flying Housewife (athletics, Fanny Blankers-Koen), Flying Dutchman (tennis, Tom Okker), many Flying Finns and three versions of the Flying Scotsman (rugby player, darts player and cyclist). Enough now, lads.

If teams (Panthers, Cougars, Lions) have historically searched the animal kingdom for inspiration, then individual nicknames, too, have been mined from an entire menagerie of snakes (Black Mamba, Kobe Bryant), cattle (Raging Bull, Jake La Motta), ducks (El Pato, Angel Cabrera) and assorted big cats.

Indeed, long before Eldrick Woods, there were three other Tigers just in cricket. One was a legendary Indian captain, M.A.K. Pataudi, who had one eye, was married to a actress, loved practical jokes and was my boss at a sports magazine.

But nicknames are a dying art and if The New York Times mourned the disappearance of sobriquets in 2011, now it is grimmer still. Look at the world's greatest athletes - Roger Federer, Lionel Messi, Cristiano Ronaldo, Tom Brady, Stephen Curry, Usain Bolt, Lewis Hamilton - and there's not a memorable moniker between them. FedEx has as much poetry as you might find in a roadside leaflet.

In the Times, John Branch wrote of the great nickname's passing that "maybe it reflects a loss of intimacy and connectedness". In the business of modern sport perhaps the room for the affectionate informality of the past is shrinking. Perhaps in the blandness of the PR-polished sporting world, irreverence and colour are a luxury. Perhaps we're caught in a world where the only relevant name is a Twitter handle.

Nicknames won't ever die but like silence in stadiums, or cricket teams hanging around in locker rooms after play to chat, they're becoming a relic. Fighters will keep nicknames alive for they have a violent urge to announce their meanness, but sometimes we need a few more laughs than Psycho or The Damage.

For that we have to dig into the past and find stories. Like the one concerning Mexico's Felipe Munoz Kapamas, who won gold in the 200m breaststroke at the 1968 Olympics. As David Wallechinsky's The Complete Book Of The Olympics states, his father was from Aguascalientes (hot waters) and his mother from Rio Frio (cold river).

And so, of course, his nickname was Tibio. It means lukewarm.