Ms Low Jia Xin, 27, intends to have just one child, although her husband would prefer two, or even more, kids.

It is just one for Ms Low because she is worried that is all they can afford, never mind that the couple have good jobs in the civil service.

Lawyer Jill Koh, 26, who will get married at the end of this year to her businessman fiance, is adamant she will have children only in her 30s.

Her reason: She wants to work and travel, which would be difficult with a baby in tow.

These were some replies Insight received when asking prospective parents why they want only one child, or are putting off having children. Over the years, the Government has thrown baby-making incentives at couples, including cash bonuses and grants, childcare subsidies, and parenthood and childcare leave, even subsidising the hefty cost of fertility treatment.

But for a country known to tackle problems swiftly and efficiently, Singapore has found itself stumped as it attempts to get more couples to have babies, and have them earlier.

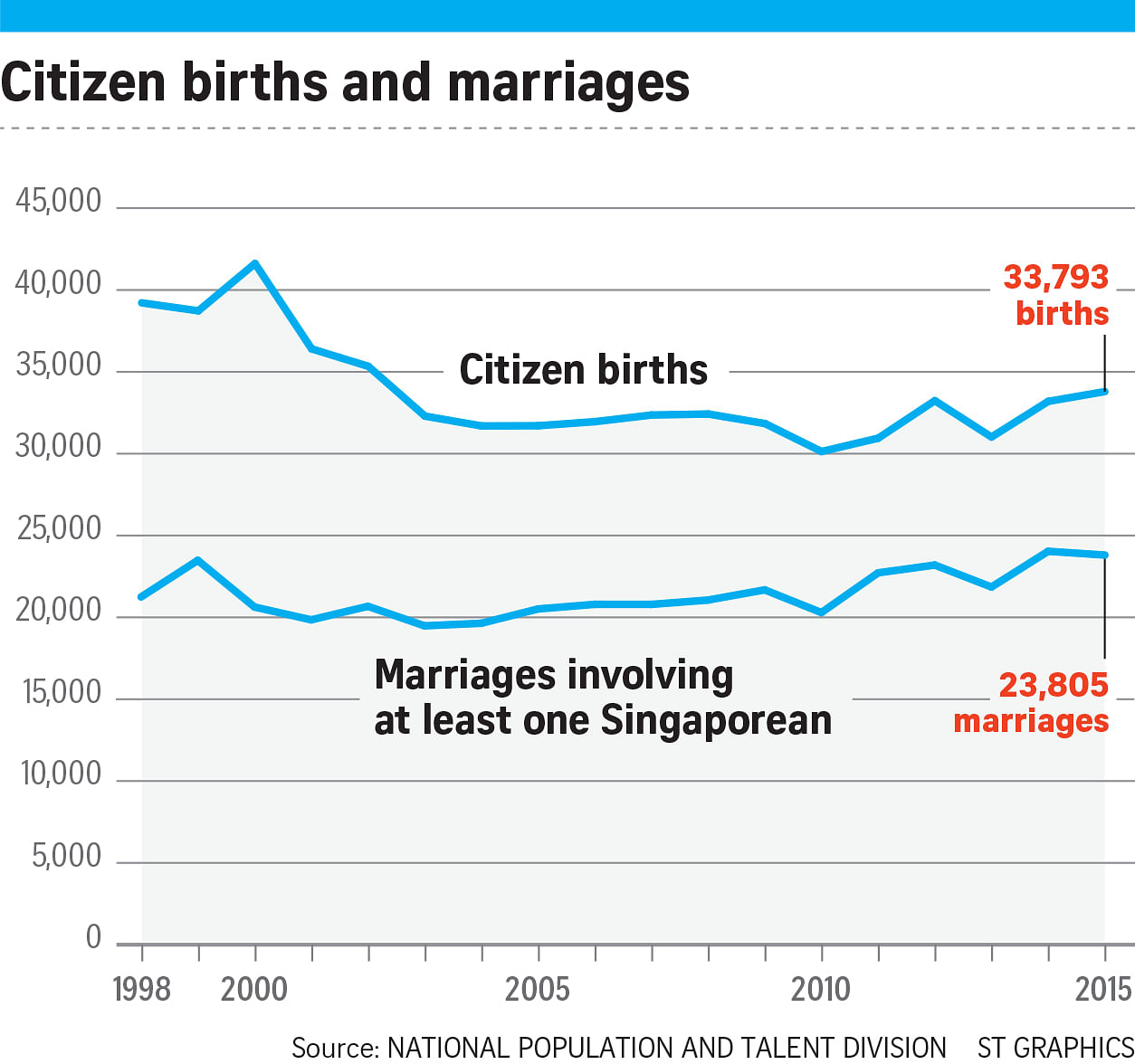

Sure, 33,793 Singaporean babies were born during last year's Golden Jubilee, the highest number in 13 years. But Singapore still struggles with ultra-low fertility rates of below 1.4 - way below the replacement rate of 2.1 to maintain population levels.

Fertility rates are based on the average number of children born to a woman who completes her childbearing years.

The push for babies was in the spotlight earlier this month when the Government dangled a new carrot, saying it may make a second week of paternity leave compulsory, in addition to the current one week.

Some commuters were also upset by the latest fertility campaign from voluntary organisation I Love Children, whose advertisements in MRT stations feature cartoon sperm and slogans like "Women are born with a finite number of eggs".

But beyond the slogans, cash carrots and the usual Chinese New Year pressuring of newlyweds, what else does it take to get couples to not only take the plunge into parenthood, but to do so earlier and have more children too?

WHY SO FEW BABIES?

Not getting married early, not getting married at all, and worries about the costs of raising kids and the state of the economy are some of the factors behind the overall fertility slump, according to those interviewed by The Sunday Times.

Ironically, Singapore's push for higher education may have worked against the push for babies.

As women focused on their studies and careers, they put off plans for marriage and parenthood.

In 1970, the median age of a first-time bride was 23.1. By 1990, this rose to 25.3, and in 2014, 28.2.

As the chances of conceiving naturally decrease as a woman hits her 30s, those who marry after 30 are not likely to have large families.

Not only that, but the proportion of currently married, divorced or widowed women who stay childless has almost tripled in the past two decades.

In 2014, 11.2 per cent of women aged 40 to 49 - the age group that is likely to have completed childbearing - had no children. The figure was 4.2 per cent in 1994.

In a 2012 paper, National University of Singapore (NUS) sociologist Paulin Straughan says that while the state's pro-family policies are important, they speak only to those who are already married. However, the issue of couples not having children is one closely linked to people getting married later.

In today's world, where courtship strongly emphasises personal choice and self-fulfilment, choosing a life partner is made more challenging, says Dr Straughan. Hence, finding a partner takes a longer time. Compounding the problem are the goals and expectations young professionals set when they start work.

Most want to achieve a higher standard of living, and covet items such as cars and overseas trips. As they build their disposable income, most are happy to put off courtship and marriage, Dr Straughan says.

This means it is no longer unusual to remain single when one reaches the late 20s or 30s. Singles no longer feel social pressure to get married and have a family, she says.

Professor Jean Yeung, director of the Centre for Family and Population Research, shares a similar view. She tells The Sunday Times that the predominant reason for the low birth rate is the low marriage rate.

"Too many young people are not getting married. For those who do get married, we do get an average of 1.5 babies per couple," she says. "More resources need to be committed to boost the marriage rate if we want more Singaporean babies."

As for those who are married, financial issues - perceived or real - seem to weigh heavily.

Ms Low, who plans to have only one child, hopes to quit her job and stay at home when the stork delivers. "It is important to be there for the child," she adds.

But this also means the family's disposable income will decrease.

And as Dr Straughan points out, while most dual-income middle- class couples are able to provide basic childcare for their children, their wants are far greater.

This goes beyond compulsory mainstream education.

Even before the children are in primary school, their parents have enrolled them in tuition and enrichment classes in academic and non- academic areas.

With extra lessons becoming the norm and not the exception, household spending on tuition hit $1.1 billion in 2013, almost double the $650 million a decade ago.

And then there are economic uncertainties that weigh on couples.

Ms Low, who is a university graduate, as is her husband, says: "The Government can give cash grants and subsidies, and they give parents a good start.

"But having a child is for the long term. We don't know what the financial climate will be or how much a university education will cost in the future."

Indeed, after the 2009 global financial crisis, 30,131 citizen babies were born the following year, with the total fertility rate tumbling to a historic low of 1.15.

NUS sociologist Tan Ern Ser, who is also a council member at Families For Life, a council under the Ministry of Social and Family Development, says that parents, especially middle-class ones, are "most serious about their offspring having sufficient opportunities and resources to make it in life".

"A pessimistic economic outlook does not give much confidence that they can provide that," he says.

CHANGING WORKPLACE CULTURE

One area that could help prod reproduction is more flexibility in the workplace.

Dr Straughan says it is not realistic for the Government to keep giving cash grants and subsidies to encourage people to give birth.

What it can give that is valued by people is time.

And she has some ideas.

First, allow couples to split the maternity and paternity leave between themselves. "The opportunity cost would not fall solely on the mother this way," she says.

Second, let companies lump childcare leave and parent-care leave under the broader term of family leave. This way, everyone with either children or parents can take time off for caregiving duties, and employers will not be able to discriminate against one particular group of employees.

Third, normalise flexi-work.

Employees can work whenever and wherever they can, which means parents can focus on their job even at home, when junior is in school or asleep.

"We need to change the organisational culture to one of innate trust," adds Dr Straughan.

"But this is also the hardest to do."

Prof Yeung also believes the focus should be on reducing the opportunity costs of getting married and having children. This means giving women equal job advancement opportunities and giving men more time and space to be involved in family matters.

Mr Desmond Choo, an MP for Tampines GRC, is all for legislating flexi-work. He made his parliamentary debut last month calling for mothers to get eight weeks of flexible work arrangement, on top of the 16 weeks of maternity leave they now get.

He argued that this will help mothers transit from caring for a newborn to full-time work. And he has first-hand experience.

Mr Choo's civil servant wife Pamela Lee gave birth to their first child, Sarah, last September.

She took annual leave to stay with the baby after her maternity leave ended. He says: "The transition period is not easy. Mothers worry about whether the baby is able to adapt to a new routine, and the baby would have developed an attachment to the mother by this time.

"We have to be very sensitive to a parent's transition needs. There is a lot of anxiety for the mother. If the workplace is not supportive, the mother may feel stuck."

Companies have told him that such a flexi-work scheme would put a strain on them.

They also said that a two-week paternity leave scheme would burden other workers.

"But the view that women should stay home as the main caregiver is already an archaic one," Mr Choo counters. "Workplaces need to be flexible and progressive in order to maximise talent.

"I believe this will be a differentiating point to people. Talent will no longer just chase after a good salary, but also a workplace that supports them having a family."

CHANGING SOCIETY'S MINDSET

That might be just the ticket for the likes of lawyer Ms Koh, who is sometimes in the office till midnight.

Having a child is not on the horizon now because, she says, "if I have kids, I will have to manage my work hours, and if I travel, it will have to be to kid-friendly places without long flights".

Ms Koh adds: "I do want to have children eventually, but I feel like I have to treasure my youth now."

But for some couples, state incentives, finances and career aspirations are irrelevant.

They have kids because they simply want them.

Take tax manager Cheryl Sia, 32, and pathologist Ng Tong Yong, 38.

The couple had their daughter, Christie, in 2013, and their son, Hansel, last year.

Ms Sia says: "It is not easy, and we are often tired. We don't have a maid and we don't drive. Our parents are also not able to help with childcare. But we want children."

The duo may have a third child when Hansel is slightly older.

Some adjustments had to be made. Both children were sent to a full-day infant care facility when they were four months old and Ms Sia's maternity leave ended.

She also switched to another role at work, as her previous project- based role meant she operated on unpredictable timelines.

Dr Ng also takes time off using his annual leave to tend to his children, if need be. He says: "Fathers are increasingly playing a more involved role in family matters. And for me, I want to do what I can to support my wife's decisions."

Government incentives have helped the couple cope with child- raising, but Ms Sia points out: "We definitely did not plan according to government grants and subsidies."

In a sign the Government will take a holistic approach to tackle the low birth rates, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong said in his Chinese New Year message that the state will support parents and their child-raising responsibilities.

The family is one's "pillar of strength and support", and "cheers us on when we are down and rejoices with us when we achieve success", Mr Lee said. "Beside babies, family is also about living a full life, experiencing joys and sorrows over a lifetime together with our loved ones."

For Ms Sia, the invaluable rewards of motherhood are "the hugs and kisses" from her little ones.

Dr Kang Soon Hock, who heads the social science core at SIM University, says of the measures the state has pushed out: "There will always be people who do not wish to have children, and these measures may not do much to change their minds. But for those who are considering children, it helps to know such support exists.

"We have to try and remove as many barriers as we can."

But will workplace support, more paternity leave, cash carrots and a more family-friendly society be enough?

Or will the younger generations' aspirational desires for better lifestyles and careers, amid worries about the financial costs of raising children, hold sway?

As Ms Low, who has decided to stay home once she has a child, puts it: "I still struggle with my decision.

"My friends are all climbing the corporate ladder, and I don't want to miss out on that. But I know that a sacrifice has to be made if we want to have children."