Today, Germans go to the polls in an election expected to see a far-right party in their national Parliament for the first time since the Nazis were defeated in 1945.

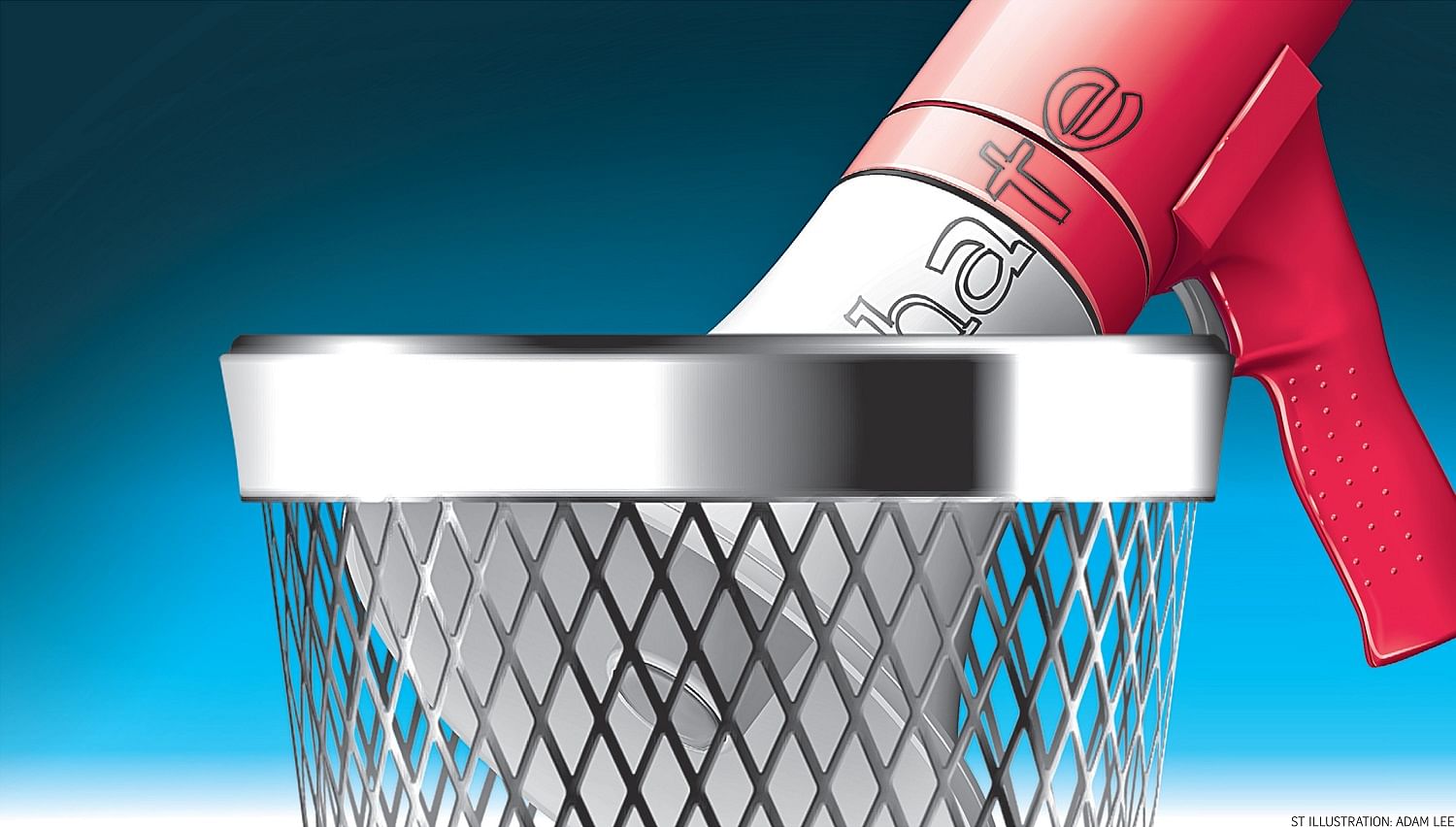

The Alternative for Germany (AfD) party didn't exist five years ago. Yet in the short time since it was formed to oppose the European Union, it has won seats in all but three of 16 state Parliaments. It is now tipped to surpass the 5 per cent vote threshold needed to win seats in the national Parliament. Its surge in support can be pinned down to two words: hate speech.

The AfD has seized upon prejudices against immigrants and minorities to win votes, called for a "Germany for Germans", and its manifesto has a section headlined "Islam does not belong to Germany". It is not just Muslims the party displays animosity towards.

One of its leaders, Mr Bjorn Hocke, this year criticised Berlin's memorial to the murdered Jews of Europe - victims of the Holocaust - as "a monument of shame in the heart of the capital".

The remarks have been roundly criticised across the political spectrum, with leaders saying such demagoguery, akin to that which fuelled Nazi Germany's genocide, cannot go unchallenged. German leaders have sought to show they are serious about such speech.

From next month, social media firms in the country must take down offensive content within 24 hours of being notified, or risk fines of up to €50 million (S$80 million).

Unfortunately, the AfD's rise in popularity has seen mainstream parties shift closer to the right in a bid to outflank it and win voters.

Similar shifts have played out elsewhere in Europe - and closer to home - in recent years.

Hate speech is at the root of the ongoing humanitarian crisis on the Myanmar-Bangladesh border - where over 400,000 Rohingya refugees have been systematically displaced and fled their country.

Politicians and those in authority in Myanmar have let prejudice fester, and in some cases fed it, resulting in a situation international observers have described as ethnic cleansing.

While militant attacks were said to have sparked the latest crisis, the disproportionate response and deep-seated tensions worsened it.

In a report earlier this month, the International Crisis Group (ICG) highlighted how a recent upsurge in extreme Buddhist nationalism, hate speech and communal violence has fed the crisis. In particular, it cited rising support for the prominent Association for the Protection of Race and Religion, or MaBaTha. Burmese monk Ashin Wirathu, who led its precursor 969, has argued that good Buddhists should not mix with Muslims, who he likened to snakes.

"Some prominent monks and laypeople within MaBaTha espouse extreme bigoted and anti-Muslim views, and incite or condone violence in the name of protecting race and religion," said the ICG report. "There is a real risk that these actions could contribute to major communal violence."

The thoughts and actions of an extremist fringe cannot be allowed to tar an entire country or faith community - whether Buddhist or Muslim - and must not set the tone.

So it is welcome that Myanmar leader Aung San Suu Kyi in a speech last week condemned all human rights violations in Rakhine state, saying those responsible would face the law - even as some feel she did not go far enough. "Hate and fear are the main scourges of our world," she said. "We don't want Myanmar to be a nation divided by religious beliefs or ethnicity or political ideology. We all have the right to our diverse identities."

Hate speech can be tough to quantify, but it has become more virulent globally in recent years.

To an extent, some of it has been fuelled by extremists and terrorists who commit unjustifiable acts of terror and claim to be acting in the name of Islam. Their acts have been roundly condemned by Islamic scholars. Yet such violence has unfortunately sowed distrust and fear of Muslims in many societies.

Nothing can justify a response rooted in prejudice.

Singapore residents have not been spared this tide of hate speech and Islamophobia, as a scroll through social media postings on the Rohingya crisis shows.

However, it is heartening that there have been voices of calm and reason online - urging people to not let tensions abroad disrupt the longstanding harmony between people of different faiths here.

It is also especially heartwarming that soon after the latest escalation of violence in Rakhine state, the Singapore Buddhist Federation made a statement calling on all parties to stop all acts of violence. The federation and Buddhist institutions also strongly supported the fund-raising effort initiated by the Muslim community in Singapore to provide much-needed relief to victims, saying: "Humanitarian consideration should transcend all man-made boundaries, be it race or religion."

Similar displays of solidarity will be needed should similar tensions arise - here or abroad.

There is reason to not be complacent. Several incidents touching on hate speech made the headlines this year, giving cause for concern.

Here are three of them.

One, a video surfaced on social media early this year of a mosque imam from India who made offensive remarks about Christians and Jews. He pleaded guilty, and was fined and repatriated.

Two, in June, the word "terrorist" was found written on an image of a Muslim woman on the construction hoarding of the upcoming Marine Parade MRT station. Police are investigating the act of vandalism.

Three, earlier this month, the Home Affairs Ministry revealed that applications for two foreign Christian preachers to speak here were rejected, on the grounds that they had made denigrating and inflammatory comments about other religions. One had referred to Buddhists as "Tohuw people", using the Hebrew word for "lost, lifeless, confused and spiritually barren" individuals, and the other had called Islam "an incredibly confused religion" interested in "world domination".

Each of these cases could have sparked considerable unease - and even unrest - had people insisted on their freedom to preach what they felt their faith called for, or to express their thoughts openly, even if others are gravely offended by it.

Yet not only did the authorities respond fast, and religious leaders came on board, but the decisions also appear to have been accepted by many Singaporeans. The episodes could have flared up but did not.

Such adept handling of these cases is possible only because there is confidence of wide public support for such moves.

The manner in which these incidents played out also offer grounds for confidence that society can emerge stronger from future such episodes should they surface.

Religious leaders took the lead in calming followers, let the law take its course, accepted the outcome, and crucially, reiterated the need for people to be mindful of our multi-religious society.

In the imam's case, Mufti Fatris Bakaram made clear that the words used " have no place in today's Singapore where we as communities live in peace and also in harmony". The imam apologised for his remarks before leaders of various faiths, and also visited the Waterloo Street synagogue.

In accepting his apology, Rabbi Mordechai Abergel noted it sent a key message that the strong bonds of friendship between the Jewish and Muslim communities here "are not affected, and we share so much more than what divides us".

As for the preachers, the National Council of Churches put out a note advising pastors to "exercise due diligence and careful discernment" when inviting foreign guest preachers - "to preserve the harmonious religious environment that currently exists in our nation".

Council president Rennis Ponniah and general secretary Ngoei Foong Nghian said in the note: "Religious polarisation can so easily be exacerbated by sweeping and insensitive statements, more so by leaders and preachers who are not familiar with or appreciative of the fabric of inter-faith relations we have built up in Singapore over the years."

One common thread running through these faith leaders' messages is that there is no room for hate speech on this island, whether home-grown or imported.

Singapore is fortunate that many of its religious leaders have a long history of cooperation and respect that have been carefully nurtured over the years, dating back to the formation of the Inter-Religious Organisation in 1949.

The Government is reviewing its laws on religious harmony to ensure this state of affairs continues.

Individuals too have a role and a responsibility to be alert to hate speech, online and offline.

People should counter hateful sentiments and prejudices that, if left unrebutted, could sink in and affect the level of trust people have in one another here.

It is unfortunate that some of these sentiments have surfaced among a minority of individuals in the wake of the first reserved presidential election.

In a world increasingly fractured along racial and religious lines, President Halimah Yacob's inauguration is a visible symbol of Singapore's commitment to a multiracial, multi-religious ideal - notwithstanding the disquiet seen over the change in the law or her election walkover.

Madam Halimah herself underlined the importance of tackling the twin threats of radicalism and Islamophobia in an interview with this newspaper last month. She feels that at the core, combating both threats requires people to respect one another as fellow humans.

"If we want to be treated well, we should treat other people well. If we want respect, we should treat others with respect," she said.

The President is a unifying figure and symbol for all Singaporeans.

She also serves as a reminder of what this country stands for, at home as well as abroad.

At a time when global trends have put many Muslims, especially those who are minorities, under the spotlight, the fact that Singapore's head of state is a Muslim woman is a strong statement of a secular state's respect for diversity - and rejection of discrimination.

At Madam Halimah's inauguration as Singapore's eighth president, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong said: "In an age when ethnic nationalism is rising, extremist terrorism sows distrust and fear, and exclusivist ideologies deepen communal and religious fault lines, here in Singapore we will resist this tide."

There is room to be optimistic that Singapore can do more than resist this tide. It can signal to like-minded allies and others that, tough as it may seem, hate speech can and must be fought, and the battle against bias won.