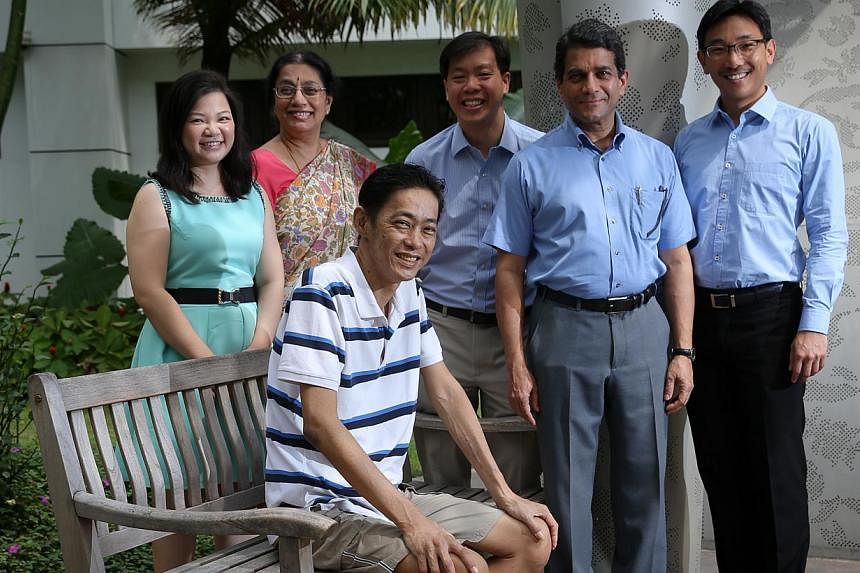

Mr Seow Hock Lin, 43, who has been plagued by kidney failure for two years and diabetes for more than 20, is enjoying a new lease of life after receiving not just one but two new organs in October.

The father of four children aged two to 17 is only the second person in Singapore to have undergone a combined pancreas and kidney transplant.

Mr Shawn Huang had the first such transplant in 2012, and is doing well.

The Ministry of Health (MOH) had set up a five-year joint National University Hospital (NUH)- Singapore General Hospital (SGH) programme in 2011 to support such transplants.

Mr Seow did not have to pay for the surgery as he is fully covered by Medifund, the Govern-ment's safety net for the poor.

While there is funding from the MOH and expertise in doing these transplants here, it is a challenge getting two suitable organs.

For one thing, the Human Organ Transplant Act - under which organs can be taken from people who die in hospital, unless they have opted out of the scheme - does not cover the pancreas.

More importantly, it is better for the pancreas to be from someone under 30, as a transplanted pancreas loses half its viability in 15 to 20 years and another half in the next 15 to 20 years.

This was why it took two years before the second such transplant was done on Mr Seow, who received the organs after the family of a teenager who died unexpectedly of a stroke donated them.

Both he and Mr Huang suffer from Type 1, or childhood diabetes, a condition by which the body cannot produce any insulin at all as the pancreas does not work properly.

Unlike patients who have the more common Type 2 diabetes, where insulin is still produced but not used by the body properly, those with Type 1 often suffer from wild fluctuations of blood sugar levels that land them in hospital several times a year.

A significant proportion of diabetic patients develop kidney failure. For Type 1 patients, once their kidneys fail, they are at constant risk of hypoglycaemia or very low blood sugar levels that could lead to seizures, brain damage or even death.

"For them, there is always the fear that when they go to sleep at night, they might not wake up the next morning," said Professor K. Madhavan of the National University Health System (NUHS).

He and Dr Tiong Ho Yee, also of NUHS, did a retrospective search and found that from 2001 to 2011, a total of 95 people here with Type 1 diabetes had renal failure.

Of them, only 35 are still alive at the end of that 10-year period.

For Type 1 patients, a kidney transplant alone is not good enough as their inability to produce insulin would destroy the new kidney in 10 to 15 years.

Dr Victor Lee of SGH, who with Prof Madhavan are directors of the programme, said transplanting both organs makes sense, as the patient would already be on drugs to prevent rejection of the kidney. Having a new pancreas would cure them of their diabetes.

Currently, two Type 1 diabetics with renal failure are on the waiting list for the combined transplants.

As for Mr Seow, who quit his production supervisor job after his kidney failed two years ago, he hopes to find a new job in a few months.

Mr Seow was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes in his late teens when he was still a polytechnic student. Shortly after he turned 40 in 2012, his kidneys failed and he needed to go on dialysis.

"I was very sick and had no energy," he recalled. He did not even have the energy to take an interest in his children, something he hopes to make up for now.

Now, more than a month after the transplant, Mr Seow said: "I am very grateful to them for giving me a new life."