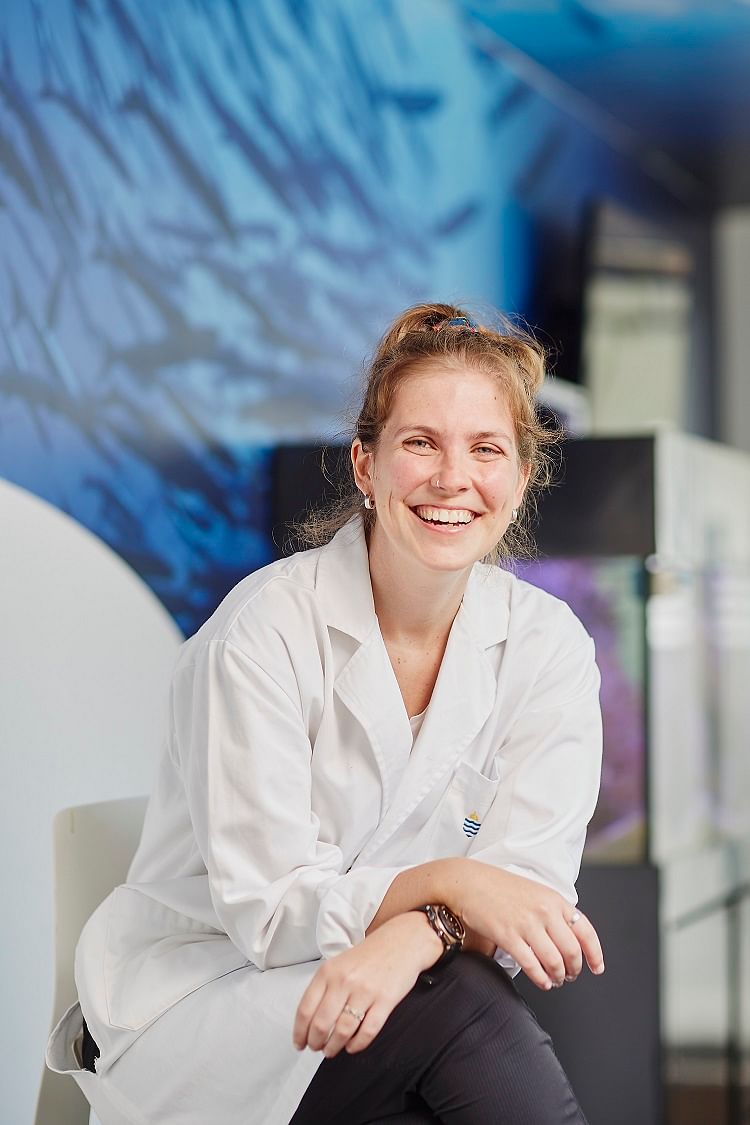

As a young girl, marine researcher and conservationist Naomi Clark-Shen remembers being afraid of what lurked in the dark, cold depths of the ocean. Her family would often drive up from Singapore to Malaysian islands such as Tioman and Rawa for snorkelling holidays, and while they would snorkel quite far out, she would often remain in very shallow waters.

"I have a very vivid imagination and I would scare myself by thinking about big sharks and other predators coming out of the deep. Sometimes, I was even scared of being in the deep end of swimming pools!" the 30-year-old recalls.

All that changed when Ms Clark-Shen turned 14 and watched "the most amazing show on National Geographic about sharks". From then on, she was hooked. "My interest in sharks turned my fear of the ocean into curiosity."

At 17, she got her scuba diving licence and a year later, she headed to the United Kingdom to pursue an undergraduate degree in animal behaviour at University of Exeter and a master's in marine science at Plymouth University. Upon graduation, she became a freelance conservation consultant, working on a variety of projects in conservation (primarily marine) as well as content production and writing for organisations such as the World Wide Fund for Nature and Animal Concerns Research & Education in Singapore.

In 2017, she initiated an independent project with a friend to survey the sharks and rays found at Singapore's fishery ports. After three years of the same surveys at the same fishery ports, she gained a deep interest in blackspot sharks and blue-spotted maskrays or stingrays. The blackspot shark (carcharhinus sealei) is a small shark species that rarely grows beyond 90cm long, while the blue-spotted maskrays (neotrygon spp) is a small stingray species that does not grow over 40cm in width.

"When we were doing our surveys at Singapore's fishery ports, both turned up in quite high volumes. Then we heard from merchants and suppliers that their numbers have actually dwindled over the years," Ms Clark-Shen says.

This finding concerned her, so she began to think about what she could do to save them, such as with more in-depth knowledge about their life history - from how long they live and the age at which they reach maturity to how many young they have and whether they give birth seasonally.

She explains: "These answers are important for conservation. For example, if an animal takes a long time to reach maturity, produces very few young, and only gives birth once every few years, they are very vulnerable to fisheries and their populations can plummet if fishing pressure continues.

"On the other hand, if an animal reaches maturity quickly and produces many young throughout the year, they are more resilient to fisheries, and fishing practices may just need some tweaks to keep their populations stable."

Going deep

To take her research to the next level, Ms Clark-Shen decided to pursue a Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) in marine science focusing on the life history of blackspot sharks and blue-spotted maskrays at the Singapore campus of James Cook University (JCU). Choosing JCU was a no-brainer as the institution is a world leader in shark and ray science.

She says: "I knew that the mentorship, expertise and connections at JCU would be top-level. Before joining the programme, I had collaborated with Dr Neil Hutchinson and Dr Andrew Chin, both professors at JCU, and I thought they would make good supervisors. They encouraged me to do a PhD."

The particular method she is using in her PhD research - life-history analysis for sharks and rays - is also not known to other universities in Singapore. Ms Clark-Shen, who does not believe in killing animals for research, says her supplier works with commercial fisheries to supply her with sharks and rays each month. She conducts general dissections to check if they were carrying any babies, assess the maturity of their gonads and to remove vertebrae to determine their age.

Other laboratory techniques she uses include a DNA analysis to confirm the marine species and a diet analysis to see what they eat.

Ms Clark-Shen's research is cutting-edge as she is producing novel science about the blackspot shark and blue-spotted maskrays that have not been well-researched. "Generally, smaller shark and ray species get overlooked because they aren't as 'sexy' as the bigger ones," she says.

By shedding light on the life history of these species, she hopes to help fisheries managers and conservationists understand how vulnerable they are to fishery pressures, and to devise suitable management measures to help them.

"For example, if we discover that one of the species only gives birth seasonally, maybe fishermen can release animals back into the sea during that particular season," she explains.

Life on campus

Ms Clark-Shen admits that life as a PhD student took some getting used to.

She elaborates: "You need to get used to the fact that you will be working mostly alone on your research topic for the next three to four years. There were times at the beginning when I felt a bit isolated. Of course, I have gotten used to the rhythms of the research and found a support network on campus since then.

"I'm very happy and loving the whole experience. Because the research is yours alone, you can be independent in how you approach the work, adapt to challenges and structure your schedule each week."

Her supervisor has also struck a very good balance with her. "He trusts me to get on with things by myself but is always there when I need him, whether during or outside our weekly meetings. He is easy-going, but cracks the whip when needed. For example, he put his foot down and insisted I learn DNA analysis, a new technique I was hesitant about. He also picks up on when I'm stressed and always manages to reassure me. The relationship is more of a friendly mentorship than a teacher-student one."

Ms Clark-Shen feels that the unique skill set she is being equipped with and the rigorous approach to research and greater knowledge will help advance her career. She already feels more confident in this field of work.

Her goals after her PhD are centred on continuing to help animals. As an animal welfare advocate, she wants to explore a link between marine conservation and marine animal welfare. She is also considering writing children's books on conservation.

Her advice to those considering doing a PhD is: "Wait until you find something you're truly passionate about and want to spend the next three to four years (and beyond) specialising in.

"Don't rush into one after your undergraduate degree either. Work for a spell or maybe even do a master's first. These experiences help to build character, so you will be more confident and capable when taking on a PhD."

The Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) at JCU is open to those looking to specialize in various fields of study, including education, social sciences, game design, banking and finance, tourism, psychology, aquaculture, and marine ecology.