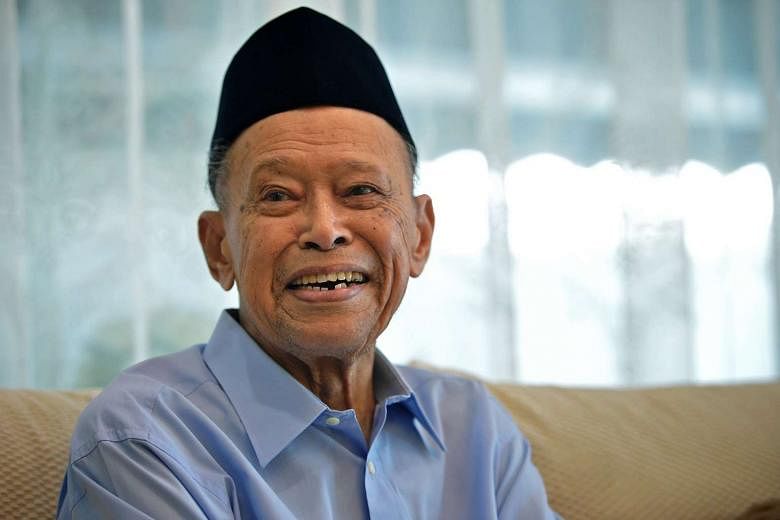

Mr Othman Wok's death turns another sad page in the final chapter of Singapore's beginnings. As an unplanned child of international politics, Singapore - a multicultural island with an experience of communal conflict - faced, at independence in 1965, uncharted waters alone.

Mr Othman, as one of the signatories of the Separation Agreement with Malaysia, carried, perhaps, a greater weight than most upon his shoulders. He traced his lineage to pre-Raffles Singapore and was both Malay and a Muslim - a pedigree leading him to be branded an infidel and a traitor by Malay extremists for being a member of the PAP, a multiracial political party.

Mr Othman's greatest contribution to present-day multicultural Singapore is, undoubtedly, his belief that diversity need not be divisive - inter-communal differences within a nation are not necessarily incompatible with shared values and a shared destiny. His position took courage for an individual who - to use parlance of today - had more skin in the game than most.

The attention paid by Mr Othman to the Malay-Singaporean community was akin to the late US Supreme Court Justice Harry Blackmun's view on race relations in the United States - that "to treat some persons equally, we must treat them differently".

Mr Othman appreciated the unease some Malays may have felt immediately after independence. Overnight, the community found itself becoming a minority within a predominately Chinese polity. As the sole Malay Cabinet member, Mr Othman assured the community that its needs and affairs would continue to be looked after.

As social affairs minister from 1963 to 1977 and minister for culture from 1965 to 1968, Mr Othman was pivotal in ensuring the continued development and progress of Malays, post-independence.

For example, he introduced specific initiatives aimed at advancing the welfare of the Malay and Muslim communities. To raise the socio-economic status of Malays, Mr Othman saw to it that free education was provided from the primary to tertiary levels. In addition, the foundation of Yayasan Mendaki, an organisation that still plays a vital role in the Malay community today, was laid.

Arguably, one of Mr Othman's greatest contributions to the Malay-Muslim community was the development of the Administration of Muslim Law Act, which led to the establishment of the Islamic Religious Council of Singapore, the Syariah Court and the Registry of Muslim Marriages.

The Mosque Building Fund was also established, to guarantee the building and conservation of mosques in Singapore's housing estates as the country developed.

Another significant legacy was the establishment of the Singapore Pilgrimage Office, the first formal system of haj registration that allowed for the proficient and effective administration of haj matters for Singaporean pilgrims.

However, Mr Othman was not an individual focused on the needs of only one community. He, instead, understood that Singapore needed to be shaped into a community of communities - a tightly woven quilt. He argued for a nation that is not only multiracial and multi-religious, but also, simultaneously, Singaporean.

As social affairs minister, he introduced initiatives to bolster commonality and national identity.

For example, a national sports stadium was built to bring a newly created people together. Sports was to be a means through which Singaporeans could create and share a sense of identity. For those old enough to remember the Kallang Roar during the 1970s and 1980s, there is little doubt the stadium fulfilled its raison d'etre.

Further, the provision of social welfare to all was, for Mr Othman, another way to develop a sense of making progress together. He understood how Singapore's development depended on the overall progress and upkeep of its people, regardless of their racial or religious affiliations.

Following from this, Mr Othman was dedicated to improving the lives of disadvantaged groups such as the disabled and the aged. He also served to advance the rights of workers, and fought for better wages and working conditions via the labour movement.

All these were based on an idea that, despite Singapore's inadvertent nationhood, the polity possessed the agency and the energy to look beyond its differences and find unity in difference.

Has Singapore developed into the Singapore Mr Othman literally signed up for?

Most would probably agree it has. Singaporeans are generally comfortable with having multiple identities, such that they can simultaneously be part of the nation as well as part of an ethnic group and religion. The possession of a multiplicity of identities sits easy as these different identities are not seen to be in continual contestation with one another.

In effect, as Mr Othman wanted, Singapore has indeed become a community of communities.

Is the Singaporean project sustainable?

The truth of the matter is that no one knows. The nation has surmounted previous challenges to achieve inter-communal harmony and will, no doubt, face more in time to come.

Perhaps, the only way to ensure the project keeps ticking is to continually work at it with the confidence Mr Othman had in the nation. When confronted with an issue, his response was "we will get together, to face it and solve it. I have that confidence".

- Norman Vasu is deputy head of the Centre of Excellence for National Security at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University. Nur Diyanah Anwar is a research analyst in the Social Resilience Programme in the same centre.