It is hard to tell how effective the campaign was, though there is evidence of at least some impact. In May 1931, The Straits Times said that a total of 250 men had taken up the offer and the dossiers of 100 men were still at the newspaper's office, having not found any takers. Perhaps some of 150 others found jobs.

Replying to a reader who, in February 1932, called for the free advertisements to be continued, the newspaper said a central employment registry might be a better idea.

The 1930s were times of acute distress, to a degree unseen till then or since. The Straits Times interspersed its reports on the big economic picture with personal stories of loss and hardship.

"Malaya has suffered a serious setback in the prices of its chief commodities, and though no one likes the word 'slump' it has to be admitted we are in the midst of acute trade depression," The Straits Times wrote on Oct 1, 1927, warning of rude shocks ahead.

"Those sure barometers of industrial conditions, the brokers, declare that they have never known a time when the market was in a more depressed state. There is little activity in shares and most people are adopting a policy of waiting to see what the next few months will bring forth. Tin and rubber are both very depressed markets."

Six years later, the crash was a reality no one could ignore. "It is a hard, wearying, worrying, nerve-racking grind, and long before the end of the month comes we have nothing left - not a cent in the house. We have been able to keep going in the past by pawning small articles of jewellery and so getting some additional food. Now everything has gone, including my wife's wedding ring, and my signet ring and we have nothing else to pawn." This account came from a European mechanical engineer who was thrown out of work.

The letter brought out an outpouring of sympathy from readers. Food, clothing and money for this unnamed family from anonymous donors found its way to The Straits Times. One reader offered them a place to stay, waiving the rent, and this European family stayed on in Singapore. Hundreds of others were not so lucky. Without jobs or prospects, they were repatriated.

By this time, an exodus was under way.

On June 6, 1930, The Straits Times tore off the blinkers: "From time to time we are warned that if the slump continues, thousands of coolies will be faced with starvation, but always hitherto we have been left with the impression that the trouble is not yet; it is merely something that may develop and we would be wise to prepare in advance to meet a possible crisis. Actually, there is ample and tragic evidence available of the terrible consequences of existing unemployment among the coolie class."

The reference to the "coolie class" sounds condescending, even insulting, today. The Straits Times was, after all, a part of the colonial structure. Yet, in a notable way, the newspaper was ahead of the government, taking a humanitarian - and not simply a colonial - view of affairs. Eventually, it was a strand of this humanism that turned public opinion in Britain against the exploitation, hastening an end to colonialism.

The Straits Times saw its duty in ensuring Singapore's continued prosperity by reporting on events that it thought the authorities were not responding to, pushing the colonial government to take what it saw as an "opportunity for statesmanship" instead of governing on the assumption that it had little obligation towards welfare.

On Nov 21, 1932, the newspaper published an extensive article submitted by a reader in Kuala Lumpur: Are We Overdoing Retrenchment?

Under a sub-heading Optimism Wanted, the writer asked: "Cannot our newspapers tell us more of the actual and potential wealth of this country? Must we always be told what a mess our country is, how critical are the finances of our Governments, that we must scrap or sell our railways, and the 'Sea Belle' and close down Government House when this country for its size and population is actually and potentially one of the richest, if not the richest, in the whole world."

The Sea Belle was the Governor's yacht.

In a similar vein, editor George Seabridge criticised the defeatist attitudes which were delaying recovery in an editorial titled Too Much Gloom.

"To ignore the very real difficulties that have arisen in the past two years would be to invite disaster; to go to the other extreme, however - to talk of Malaya going back to jungle and Singapore becoming a fishing village - is ludicrous. Yet that extreme view does exist, and it is a view which should be fought vigorously because the dissemination of it tends to discourage enterprise and to retard any concerted effort on the part of the trading communities to extend their activities, rather than to wait patiently - and sometimes with very little confidence - for that problematic boom in which they are to recover in full all the profits which they are losing at the present time."

The Straits Times instead consistently advocated a policy - seen most recently in the global financial crisis of 2008 - that urged the economic pump be primed with more spending.

It walked the talk. In an advertisement sub-titled Advancing Through The Slump, the newspaper announced its new office building and state-of-the-art rotary press on Oct 10, 1933.

It added: "Because times are bad, there is no reason for loss of confidence in the country's future, and gloom and fear will get one nowhere. In this direction, The Straits Times Press has been by no means backward, indeed, with all modesty, it can claim to have shown the greatest courage."

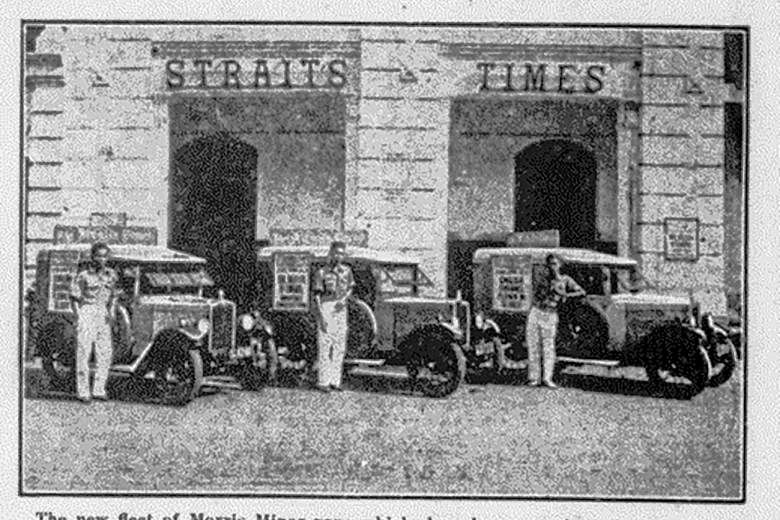

As other companies cut costs, The Straits Times bought a fleet of Morris Minor delivery vans to deliver copies upcountry and launched the first Sunday paper in Malaya to great success.

For Singapore, the Great Depression was not just an economic event. It led for the first time to immigration controls, supported by The Straits Times, which clamped down on the inflow of men from China but let in women and children.

The result was manifest within years. Singapore transformed from a migrant society into a truly immigrant one.

It led to another profound change - the emergence of a truly resident society for the first time. The male labourer who could be housed dormitory-style in Chinatown could no longer be the way forward. In time, policies were pursued to stop the growth of slums and drive investments into housing.

1920

THE SLUMP

The Straits Times expresses disapproval of Sir Laurence Guillemard's appointment as Governor and High Commissioner, for he has no experience in overseas administration and does not heed warnings that an economic slump is imminent. The slump hits six months after his arrival. The Straits Times promotes schemes to restrict the production of rubber, the mainstay of the Malayan economy, to counter the slump. When the government eventually curbs production, there is much relief.

Editor Alexander William Still's concept of a newspaper acting to exercise influence for the benefit of the country raises the public stature of The Straits Times. When he dies in 1931, he is remembered for his multiple contributions. The Sin Kuo Min Press comments: "What he did was for the country and for the people who had their interests in it, and non-Europeans as well as Europeans had much to thank him for it." The Times, London, in an obituary calls Mr Still "great as an editor but greater as a man".