At about 10pm on the night of Nov 13, 2015, Chief Superintendent Dimitri Kalinine received a call at home. There had been a shooting at the Bataclan theatre and seven officers from his police unit were on the scene.

He did not know it then, but Paris was in the middle of a series of near-simultaneous attacks that would leave 130 people dead and hundreds more injured.

Earlier, three suicide bombers struck the Stade de France stadium where a football match was going on, and a series of mass shootings took place at cafes in the 11th arrondisement of the city.

Fortunately, mass carnage was avoided at the stadium, after a security guard found a suicide vest on one of the bombers. All three detonated the explosives outside the stadium where there were far fewer people. They killed one person.

The bloodiest scenes unfolded at the Bataclan, where three attackers stormed the concert venue and killed 90 people.

That night, worried about his officers and what was happening, Mr Kalinine, the Paris Prefecture Police's third arrondisement (administrative district) central commissioner, sped to the scene.

"There was confusion reigning on the radio. It was difficult to understand what was happening in France, in Paris, at that time," he recalled.

Mr Kalinine, along with other French security officers, recounted what happened on that fateful night during the Milipol Asia-Pacific 2017, a homeland security conference held at the Marina Bay Sands Convention Centre last week.

His men were among the first security forces on site, he said. They had been called over by the theatre's security guard while they were handling a traffic accident nearby, and found themselves at the Bataclan "just as the terrorists began their carnage".

His officers, who had only 9mm pistols and light bulletproof vests, found themselves hopelessly outgunned by the attackers who were using Kalashnikov assault rifles.

"Frightened by the violence of the scene and the metallic noise of the Kalashnikovs, they put themselves behind their vehicle, while the door of the theatre closed," he said.

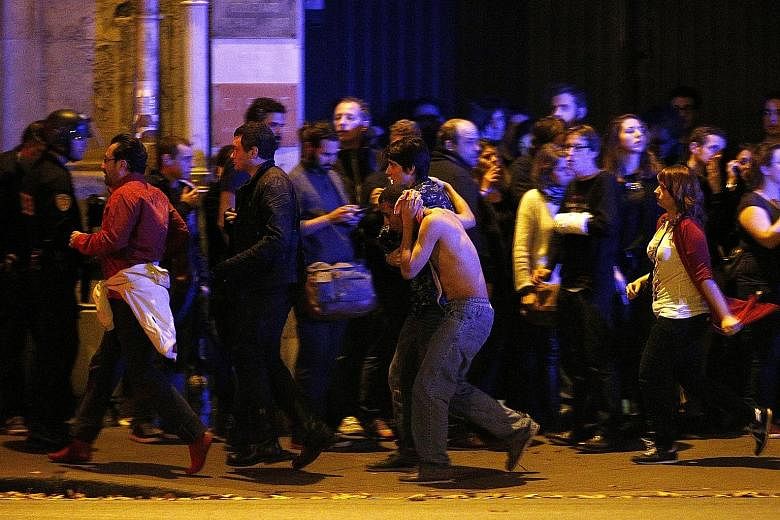

All they could do then was to try and provide emergency care to those fleeing the theatre.

"All the victims they had tried to rescue died - their wounds caused by assault rifles were too serious and they lost too much blood to be saved," he said.

Mr Kalinine arrived a few minutes after a senior officer from the anti-crime branch and his driver, entered the theatre and shot at one of the gunmen, who then blew himself up.

That enabled the massacre to stop, he said.

Soon after, special forces began entering the theatre.

Chief Superintendent Eric Gigou, deputy head of the anti-terrorism unit of the police special forces, said his officers knew that the attackers were using hostages as human shields.

"When you are on the ground, you have to solve two crises: Save people from the terrorists and, at the same time, save people who are wounded and injured," he said.

As the special forces team advanced, Mr Kalinine and his officers moved casualties out of the theatre behind them, pulling out street fences to use as makeshift stretchers.

At that time, firefighters and rescue personnel had been instructed to stay away as they were unarmed and not wearing bulletproof vests, said Mr Kalinine.

It was gruesome work that lasted about two hours.

"The scenes of war we have seen have all permanently marked us. We won't forget seeing things such as mobile phones still vibrating on dead people," said Mr Kalinine.

Eventually, he and his officers were told to leave the theatre as the special forces made their final assault on a room on the second floor, where the two attackers were holed up with hostages.

Special forces officers entered the room and advanced behind a metal shield, which was hit by 27 bullets.

They managed to shoot one attacker and the second one blew himself up.

FRONTLINE OPERATIONS EVOLVE

The siege of the Bataclan was over, but lessons from that night have changed how French security forces operate, said officials.

For starters, frontline officers - the everyday police conducting patrols on the ground - have been equipped with assault rifles, ballistic helmets and heavy bulletproof vests and shields.

These officers, who are likely to be the first responders in any attack, have also been trained to handle such incidents, added Mr Kalinine.

The key is to react quickly when an attack happens to minimise casualties, said Mr Gigou.

Singapore is also doing something similar. First responders from the police are made up of trained officers from patrol units known as the Ground Response Force and Emergency Response Teams (ERTs), and they are trained in counter-assault skills.

The ERTs are crack troops equipped with HK-MP5 submachine guns and mounted on motorcycles so that they can be anywhere on the island in minutes.

After the attacks, the French government also developed a smartphone app that can inform members of the public and advise them on what to do when there is a terror strike. This is similar to the SGSecure app that the Singapore Government has developed.

Mr Herve Tourmente, deputy director at the Directorate General of Civil Security and Crisis Management, said civil rescuers will also play a bigger role.

They have been trained and equipped with helmets and bulletproof vests, so that they can take care of victims as close to the action as possible, he said.

"A new operational doctrine has been implemented and the services are now training," he said.

Danson Cheong