In the early 1920s, a list of exceptionally bright children was assembled for a study about growing up as a genius.

These individuals became known to psychologists, affectionately, as the "termites", after Professor Frederick Terman, the Stanford researcher who began the study.

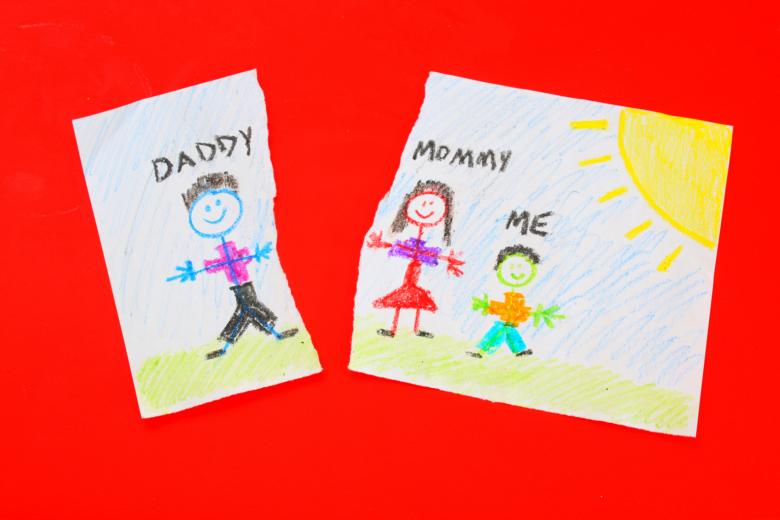

The vast majority of the group have died. Their death certificates reveal that those whose parents divorced before their 21st birthday lived four years fewer than those whose parents stayed together until at least that point.

Male termites typically lived to 76 as opposed to 80; female termites made it to about 82, instead of 86.

Overall, the termites handled life no better or worse than the United States population as a whole. They committed suicide, developed alcoholism and themselves got divorced at the national rates.

So, if parental divorce reduced longevity among the termites, it suggested worrying things about how divorce might affect all kids in the long run.

The research subjects' early deaths were pinned on higher rates of smoking, perhaps indicating a greater life-long psychological stress following parental divorce.

Times have changed since then.

While researchers have a lot of disagreements about divorce trends, most agree that divorce is less common today due to a rise in the age at which people first marry.

Divorce used to be the preserve of the upper classes. But today, lower- class couples have accounted for an ever greater share of divorcees.

Similarly, a highly-educated wife used to be linked to greater odds of divorce, but that pattern has at least weakened in European countries taken together, and is reversed in the most developed ones.

But what do these patterns have to do with how much divorce affects kids later in life?

To answer that question requires comparing divorce trends to the outcomes of divorcees' kids over time - outcomes that can reveal their levels of stress and how they have responded to stress as they have matured.

Various studies attempt this, but none over as long a period as an analysis of Swedish children.

Swedish records allow for a comparison of people born more than a century apart, since face-to-face interviews using the same set of questions have been posed to Swedes born from 1892 onwards.

Interviewees have been asked about their living arrangements growing up, the extent of parental discord that they recall, and about their mental health issues into adulthood, from insomnia to depression.

Many divorce trends over the 20th century suggest that children, on average, should have experienced noticeably less distress over time from their parents' marriage ending.

As divorce has become more common, it has become more socially acceptable. Female employment has risen and the welfare state has grown, meaning that single mothers are comparatively more able to provide for their offspring today than in the past.

Custody arrangements have also changed and children whose parents divorced in recent years are more likely than ever to maintain relationships with both parents.

But shockingly, divorcees' kids in Sweden have seen no improvements in their relative educational attainment and psychological wellbeing. To this day, they are worse off by these measures than kids whose parents stayed together.

The ongoing gap in educational performance appears to be due to families of a lower economic class becoming more prone to splitting up over the decades.

Kids born into lower-income families have always tended to do worse at school, so that trend is not due to divorce per se.

But the stubbornly lower psychological well-being of Swedish divorcees' kids cannot be pinned entirely on income.

Socio-economics may explain part of it, but, instead, lots of family arguments appear to leave long- term traces.

In short, the impact of parental divorce is often subtle and long- lasting. From the Stanford geniuses to Swedes born in the 1990s, the evidence suggests that kids whose parents have or are about to split up need more support than we realise.

THE GUARDIAN