SINGAPORE - The rustic isle of Pulau Ubin is known as a treasure trove of biodiversity. But plans are afoot to ensure that nature continues to flourish on the island in the Republic's north-east, and is not threatened by coastal erosion or sea level rise.

From next year, the National Parks Board (NParks) will begin two nature-based coastal protection projects to safeguard Ubin's northern and southern coastlines by restoring eroded areas and protecting them from future sea level rise.

These efforts follow other successful measures NParks have carried out, on Pulau Tekong and in Kranji on the mainland.

The upcoming initiatives on Ubin were announced by Minister for National Development Desmond Lee on Saturday (Sept 25), at the annual Festival of Biodiversity, which celebrates the Republic's native wildlife. This year is the tenth edition of the event.

"We will be embarking on two new and more extensive coastal protection projects in Pulau Ubin. These will be carried out in partnership with the community: one at the northern coastline, and the other in the south, at Sungei Durian," said Mr Lee at the event at the Singapore Botanic Gardens.

"This will restore the island's coastlines and mangrove habitats, and bring back more of the island's rich biodiversity by addressing ongoing erosion and habitat loss."

Ubin's northern coastline is currently facing erosion, wrought by changes in land use on the island and the impacts of waves and vessel traffic. The island was used for granite mining in the 19th century, and later for aquaculture.

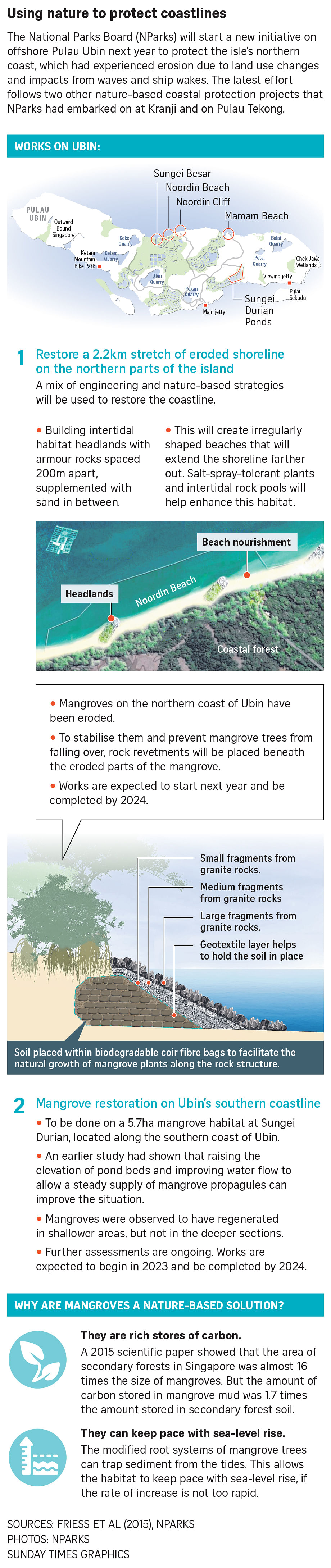

Restoration works on a 2.2km stretch of that coastline are expected to begin next year using a mix of natural and man-made infrastructure.

This includes the installation of armour rocks to form cliff-like structures, or headlands, spaced 200m apart and supplemented with sand in between, said NParks. This creates irregular, wavy beaches that will help to extend the shoreline farther out from where it is today.

To "soften" these headlands and enhance the habitat for wildlife, inter-tidal rock pools and salt-spray tolerant plants will be introduced to the area, the Board added.

The erosion is also affecting the mangroves growing along Ubin's northern coast.

NParks plans to prevent further loss of mangrove trees there by building a sloping structure made of rocks along the shoreline called a revetment to act as a barrier between sea and sand. Soil placed in biodegradable bags will be placed under the rocks to facilitate the natural growth of mangrove plants along the stony structure.

As for the southern coast of Ubin, NParks said it will be working with scientists, volunteers and marine conservation groups to assess how abandoned aquaculture ponds there can be made into richer mangrove habitats.

Even though the ponds have been fallow for years, mangrove has regenerated in only the shallower parts of the ponds, which can reach depths of 5m.

NParks said possible strategies could include elevating the pond beds and improving water flow to ensure a steady supply of mangrove propagules (or young mangrove plants) from mature plants. "This will help produce a self-sustaining ecosystem," said NParks.

Further technical assessments, planning and detailed designs are ongoing, with plans to begin works in 2023.

Mr Lee said planting trees and shrubs, as well as enhancing and restoring mangroves along Singapore's coasts, can help defend Singapore from rising sea levels, while providing key habitats for marine and coastal species to thrive.

Associate Professor Adam Switzer from the Nanyang Technological University's Asian School of the Environment welcomed Singapore's move to incorporate nature-based solutions into its coastal defence strategy.

He said research needs to continue in this area to ensure that these solutions will work, as mangroves are found in areas with very specific environmental conditions.

Said Prof Switzer: "They will only work in places with the right tides, sedimentation regime and low wave energy. That means there are relatively few places where mangroves make a suitable coastal defence. Lucky for us, one such place is Pulau Ubin."

Such a nature-based strategy was first piloted on Tekong in 2010, when NParks used a combination of man-made structures and nature to reduce coastal erosion. The project successfully stopped coastal erosion and prevented the further loss of mangrove in the area over the past decade, said NParks.

"Learning from this experience, we recently completed a similar coastal protection project at Kranji Coastal Nature Park, bordering the coast of Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve," said Mr Lee.

With the help of more than 250 volunteers, almost 800 trees and shrubs were planted to restore and enhance the coastal site, including rare species such as the Ormocarpum cochinchinense - a native tree previously thought to be extinct in Singapore.

Nature-based solutions to climate change are increasingly being discussed globally, as countries seek to reduce their carbon footprint and adapt to climate impacts.

Mangroves are habitats that can help on both fronts.

One, they are rich stores of carbon. The water-logged soil of a mangrove keeps carbon in the ground and away from the atmosphere, where it traps heat and drives climate change.

A 2015 scientific paper by scientists here showed that the carbon stored in mangrove sediment was 1.7 times the amount stored in secondary forest soil, even though secondary forests in Singapore made up almost 16 times the mangrove area.

Two, the complex root systems of mangrove trees allow them to trap sediment from the tides as they ebb and flow. This allows the habitat to keep pace with sea level rise, if the rate of increase is not too rapid.

In 2019, The Straits Times reported that land in Singapore had changed from being a net absorber of carbon in 2012 to a net emitter in 2014, due largely to land conversion from forests and other vegetated areas to settlements.

Asked if the impact of mangrove restoration efforts could make a dent on Singapore's total emissions, group director for NParks' National Biodiversity Centre Ryan Lee said forest conservation and enhancement was a long-term effort that will play an important role in Singapore's efforts to reduce its carbon footprint.

He added: "Expanding the mangrove forests, together with NParks' other greening and ecosystems enhancement efforts, helps us better mitigate climate change."

Other than for coastal protection, Singapore wants to harness other benefits of nature, said Mr Lee.

This includes planting more trees, especially in urban areas, to cool the surroundings, as well as turning concrete canals and reservoirs into naturalised rivers or lakes to enhance flood resilience.

As vegetated plots absorb more water than concrete, naturalising water bodies can help to reduce the amount of run-off in heavy rain from entering the drainage system and overwhelming it.

He added: "In these ways, nature-based solutions can help to protect our coastlines, cool the environment and improve our flood resilience."

At the same time, such solutions can also create new habitats and connect existing ones, helping Singapore better conserve its biodiversity, he said.

The Republic is already reaping the benefits of the conservation efforts over the years, Mr Lee said.

An ongoing review of Singapore's wildlife inventory by NParks and local biodiversity experts found that 40 species are now more abundant here than before.

The Straits Times reported last month that mammals on the brink of extinction are making a comeback. Five species - the smooth-coated otter, lesser mousedeer, Sunda slow loris, trefoil horseshoe bat and lesser false vampire bat - went from critically endangered to endangered.

The lesser bamboo bat is now considered vulnerable to extinction, when previously it was seen as critically endangered.

Two other bat species are now listed as species of least concern, which means they are not under threat of extinction. The narrow-winged pipistrelle had previously been considered critically endangered while the black-bearded tomb bat was deemed endangered.