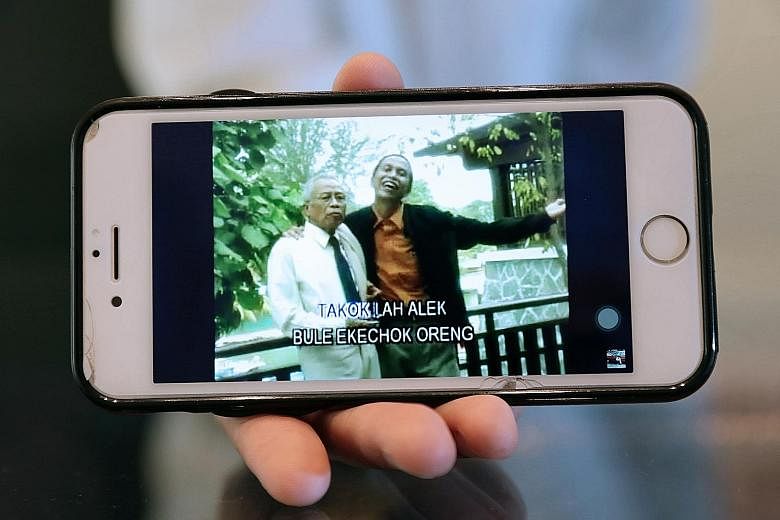

The twangy guitar strains that kick off La-A-Obe - Singapore band Kassim Selamat and The Swallows' most iconic song - are quintessential pop yeh-yeh.

But while the melody comes straight from the Malay psychedelic pop genre that took Singapore and Malaysia by storm in the 1960s, once the singing starts, an unfamiliar tongue emerges.

"Setulu bule kaperakan," croons Kassim Selamat. "Nengkene bule la ngastabe." (I used to be happy. Now I'm sad.)

This is the Baweanese language, spoken here by a shrinking proportion of people whose ancestors came to Singapore from the Indonesian island of Bawean.

Five decades after the band's heyday, Kassim Selamat and The Swallows have turned from pop sensation to unlikely language tutor.

There are at least 58,000 Baweanese in Singapore, making them the second-largest Malay sub-ethnic group after the Javanese - but most of them cannot speak the language.

Still, some here are turning to Baweanese musicians - who also include The Cliffters and Jaffar O - to pick up some Baweanese, which has long suffered from a dearth of proper learning materials.

-

What is Baweanese and who speaks it?

-

ORIGINS OF THE LANGUAGE

Baweanese is a dialect of the Madurese language, which is spoken mainly by the people of Madura Island in East Java, Indonesia. Most of the population on Bawean Island, a small island off the north-eastern coast of Java, speak Baweanese.

ESTIMATED NUMBER OF BAWEANESE SPEAKERS HERE

There are at least 58,000 Baweanese here, according to government figures from 2015. But the estimated number of those fluent in the language is low, especially among the younger generation.

A small-scale survey by National Institute of Education associate professor Roksana Bibi Abdullah found only 31 per cent of respondents - mostly aged 50 and above - were comfortable with Baweanese.

WHERE TO PICK UP THE LANGUAGE

While there are no formal, regular classes, those interested can turn to the Singapore Baweanese Association, which is active in preserving and promoting the community's culture and heritage.

It also uploads basic Baweanese lessons online.

Its Facebook group is https://www.facebook.com/groups/177271078693/

One of them is 23-year-old Hafiz Rashid, whose father is Baweanese and mother Malay.

"When I was younger, I always used to wonder: What does the Baweanese language even sound like?" he recalled. "There was this curiosity to listen to and learn the language, but most of my relatives who could speak it were long gone, and my father himself understands it but can't speak it."

His chance came in 2014 when the Malay Heritage Centre and the Singapore Baweanese Association organised La-A-Obe (or Things Have Changed), an exhibition on the Baweanese community here.

In Singapore, the Baweanese are better known as Boyanese - a colonial mispronunciation that has stuck.

Among the activities during the exhibition were language classes, which Mr Hafiz, who is currently doing his national service, immediately signed up for. Over several weeks, he picked up some vocabulary for basic conversation.

With a laugh, he said he would test his language skills on his father, to whom he would speak in Baweanese but would reply in Malay.

"I finally got to taste this part of my culture, relearn my heritage and get in touch with my identity, with what makes me Baweanese. If you can't speak the language, what differentiates you from the Malays or the Javanese?" he said.

"But it was also bittersweet. It made me realise what we're losing. My grandparents spoke this rich language, but when it comes to my generation, it's almost extinct."

After the lessons ended, Mr Hafiz continued his quest to pick up his "father's tongue" by listening to Baweanese songs and using Anak Oreng Pebien, a small but expanding Baweanese-Malay dictionary.

He tries to incorporate Baweanese words into everyday speech, using terms such as "moleh" (go back) when speaking with friends.

Meanwhile, retired teacher Abdolah Lamat set up the Baweanese Karaoke Club in Siglap South Community Centre in 2010 to revive interest in the language and make learning it fun.

"It's not just about singing, it's also about learning the language: how to pronounce words, what these words mean," Mr Abdolah, 69, said in Malay. "After all, you learn and remember easier when you're singing and having fun. Even if the members can take home a handful of Baweanese words and teach them to other people, that's enough."

The weekly sessions attract about 20 people, including non-Baweanese, and the club has translated about 30 Malay songs, including Singapore rock legend Ramli Sarip's Jangan Tunggu Lama-lama (Don't Wait Too Long), into Baweanese.

Next year, the club is teaming up with the Singapore Baweanese Association to organise a third Bawean Idol singing competition.

A 2015 study by National Institute of Education associate professor Roksana Bibi Abdullah of 105 Baweanese in Singapore found that only 31 per cent of respondents - most of them aged 50 and above - were comfortable with the language.

Some reasons for the decline, she found, are the lack of teaching materials such as textbooks, the sidelining of Baweanese for Malay and English - taught in schools and perceived to be of greater use and importance - and the rising numbers of Baweanese marrying into other communities.

Another significant factor was the Baweanese moving from pondoks - communal quarters which were cleared in the 1970s and 80s - and kampungs to housing estates.

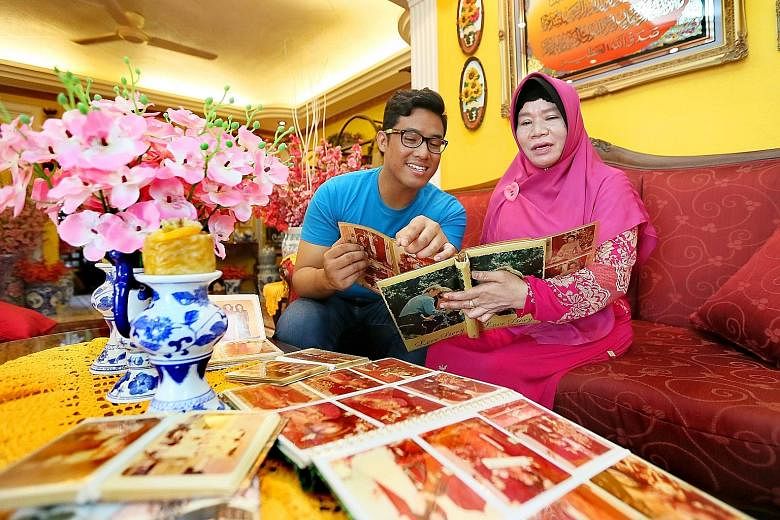

Madam Romnah Salleh, 55, grew up in a Baweanese kampung and still chats with her five siblings in rapid-fire Baweanese.

But none of her three children, who grew up in public housing estates and mixed easily with other communities, is comfortable with the language.

Her youngest child, Mr Khairul Basysyar Amran, 20, said he can understand snippets of conversations and use basic words and phrases, but nothing more.

Madam Romnah said: "It's a pity to see the language I love disappearing, but it's hard to keep it alive here. Not everyone sees the use. Where are they going to use it? That's why they forget about it."

The Singapore Baweanese Association, set up in 1934 to help Baweanese who had just arrived in Singapore find jobs and accommodation, has in recent decades set its sights on preserving and promoting its heritage and language.

It organises performances, such as theatre productions in Baweanese, cooking lessons and cultural immersion trips to Bawean Island.

Its president, Mr Faizal Wahyuni, said the association had in the past conducted language classes, but it was difficult to get students committed to attending regularly.

So the association now uploads Baweanese lessons to its active Facebook group, and this allows people to learn on their own time.

"We do find there's a bit of a revival among the younger generation. They're more interested in their heritage. They want to pick up a bit of the language. They want to know what makes them different," said Mr Faizal.

"For younger generations, it's good to know a bit about where you come from, as a moral ballast."