When Mr George Lkhagvadorj Tumur graduated with a master's in mining engineering from the Colorado School Of Mines a decade ago, he had a job offer from a US firm.

It was an attractive package: US$60,000 a year and a chance to live in the land of the free. But he opted to return home to landlocked Mongolia and a job paying a miserly US$300 a month.

Not a few people thought him dumb but Mr Tumur had his reasons. "In the United States, I would work as a mining engineer and lead an average life. Mongolia offered me better growth potential. It was not guaranteed but I took my chance," he says.

His detractors would probably crowd around him now and say: "Well played, George."

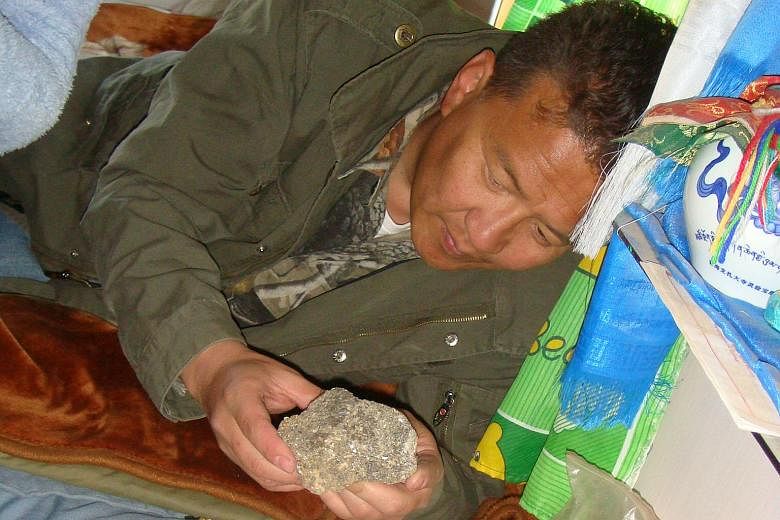

Within 10 short years, Mr Tumur, 45, not only rode the crest of Mongolia's mining boom but also played a key role in introducing Western contract mining and mineral processing technologies to the country's mining industry.

His stellar achievements include co-founding Hunnu Coal, which was listed on the Australian Stock Exchange and named IPO (initial public offering) of the Year in 2010.

"Our IPO share price was 20 cents. On the first day, it jumped to 40 cents, and 18 months later, we were taken over by a Thai company at $1.80," he says.

Mr Tumur went on to found three other companies before he made another surprising detour this year.

The mining hotshot gave up his lucrative businesses and heeded his country's call to become its ambassador to Singapore. "My principle is to listen to my heart and follow my instincts even if it seems absurd. But for every big decision, I need almost a month of sleepless nights, just thinking," he says.

Mr Tumur - the second-youngest of seven children of a railway engineer and a labour union worker - has always favoured the path less trodden. He grew up in Ulaanbaatar, the capital of Mongolia, and once toyed with journalism as a career because he loved books.

"My parents told me I started reading when I was four. One of my sisters taught me.

"We were a family of book readers and had a big family library and I started reading the classics when I was very young," he says.

But he had a change of heart as he was about to graduate from high school. "Engineering seemed to be more practical," he says.

His good grades got him a government scholarship; he was given a list of all the courses he could take and in what country.

"I looked at the list and asked what mineral processing was. The person answering said, 'I have no idea but it has something to do with this big mining company in Mongolia'," he says, referring to Erdenet Mining Corp, a Russian-Mongolian venture. "It was a famous corporation, it sounded interesting so I said okay."

That was how he ended up in Ukraine at the age of 17, with just a rudimentary grasp of Russian.

He attended the Industrial Technical School in Krivoy Rog.

"It's a mining town, a 120km-long city with eight different mining corporations. The one near the school was more than 100 years old, and we sometimes went there for practical training," he recalls.

He spent four years in Ukraine, going home only once a year.

"The journey took six days on a train, one day from Ukraine to Moscow and five days from Moscow to Ulaanbaatar," he says.

Upon graduation, he started work at Erdenet as a process technician before climbing the ranks to become a production coordinator.

The hours were long, and the working conditions taxing.

The Mongolian economy, he recalls, was also going through a tough time. The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1989 had a great impact on Mongolia, which went through a Democratic Revolution the following year, ushering in a multi-party system and a market economy.

"It was a transition economy. There was not enough energy in the country and we were getting electricity from Russia. There were daily disruptions throughout the country," he says.

"People were even on food rations; families would get coupons just to buy bread.

"Because I was working in this mining company, I was better off than the average person."

Excited by the company's plans to implement newer technology, he told his management that he would like to study in a more developed country and "do something good for the company".

When he was given the green light, he shopped around and decided on a degree in metallurgical and materials engineering at the Colorado School Of Mines.

It did not matter that his English then was barely functional.

"I only had three months of English lessons when I was working. I loved the Beatles and always wanted to know what their songs meant. I memorised the lyrics without knowing the meaning," he says.

Like Ukraine, Colorado was a culture shock. The abundance of food was overwhelming for someone from a country where food was rationed and people needed coupons to buy staples.

"When you walked down the street, people looked at you and said, 'Hi'. And you wondered to yourself, 'Have I met him before?'," he says with a chortle.

"Mongolians don't smile so much, especially to strangers, so I had to learn to smile."

All went well until his final year.

The copper cycle was down and Erdenet - which underwent changes in its management structure - told him it could not finance his studies any more. In fact, it was unlikely that he would be coming home to a job; he was on his own.

Fortunately, Dr Baki Yarar, his Turkish professor and one of the world's most famous mineral processing scientists, came to his rescue and got him the scholarships not just to complete his degree but also to do his master's.

"He told me, 'I'll get you the scholarships but you will have to work for me 25 hours a day for the next five years'," says Mr Tumur, who became Dr Yarar's research and teaching assistant.

His work ethic and perceptiveness impressed the Turkish scientist so much that the latter even asked him if he wanted to do his PhD. "He said I could take over from him when he retired but I said I wanted to start working to get experience," Mr Tumur says.

There were several job offers, including one from an American mining company, when he graduated but Mr Tumur decided to head home to Mongolia to work for a Mongolia-Russia joint venture.

His reason was simple: His studies abroad were to help Mongolia's mining industry. It took him just three months to be promoted from research and development manager to deputy general director of R&D.

The organisation's bureaucracy stymied him, however, and he left after two years to start a business importing and distributing liquefied petroleum gas.

Barely a year later, MCS - which was then Mongolia's largest holding company - offered him the post of chief executive of Energy Resources.

He was tasked to come up with a masterplan for a mammoth mining project involving a deposit of six billion tonnes of coking coal, an essential ingredient in steel production, in Tavan Tolgoi in southern Mongolia. Shortly after, the government divided the project, leaving Energy Resources to handle a site with 400 million tonnes of resources.

Within six months, Mr Tumur brought in Western mining companies to mobilise resources. He became the executive director of the company, which went on to list on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange.

But Mr Tumur shocked the industry by announcing his intention to leave. "It was a prestigious job and I was well paid but I was just an employee," says the sturdily built man, who had 1,000 employees under him at the time.

Some Australian investors had spotted his talents and approached him to start a mining operation, one that would set benchmarks for others in the industry.

"I found we talked the same language and shared the same ideas. I couldn't sleep for a month, thinking about it. But I felt I could be in charge of my own destiny."

That led to Hunnu Coal being set up. In February, 2010, it listed on the Australian Stock Exchange.

"We raised A$20 million, invested in Mongolian companies which had the deposits or resources but didn't have the money, took a percentage and funded operations. Within 12 months, we were able to find one billion tonnes of resources across three projects," he recalls.

It was so successful that Thailand's Banpu - one of Asia's leading coal miners - bought the company barely two years later.

Mr Tumur stayed on as managing director to help steer the company for the next two years.

He went on to co-found three other companies dealing in iron, copper and gold, and petroleum.

His business acumen did not escape the notice of the Mongolian government which started adopting new "economicentric" approaches in diplomatic relations with the world last year.

Feeling that it was time to give back to his country, he relinquished his corporate titles - as required by Mongolian law - and is now only an investor in the companies he helped to set up.

"My Australian partners were very supportive and positive. They said, 'We will work on the businesses, you take care of the diplomacy.' They felt it was a good opportunity for me and good for everybody."

After his appointment was cleared by the Mongolian president and Cabinet, he spent six months with its Foreign Affairs Ministry before presenting his papers to President Tony Tan Keng Yam in July this year.

"We've 45 years of diplomatic relationships with Singapore. Temasek has invested in copper and gold mining projects in Mongolia and my role is to strengthen investor and economic relations between the two countries.

"I want to create opportunities to showcase Mongolian culture and business opportunities," says Mr Tumur, who has already met several of Singapore's veteran diplomats, including Professor Tommy Koh and Professor Kishore Mahbubani.

What happens after his term of three years, he does not know.

Asked how he feels when he looks back on his life, the father of a two-year-old girl says: "I don't have any regrets. And I will continue to listen to my heart and follow my instincts."