Long gone are the days when Chinese Singaporeans named their children Ah Kow and Char Bor.

Stop a young person on the street these days and you are more likely to find a Wei Jie or Hui Min.

The more educated populace now opts for sophisticated and unusual names, or those with less common characters. The most common character for wei ("great"), for example, could be altered slightly - by changing a component of the character, known as a radical - so that the word means "precious" instead.

According to geomancers, some popular baby names these days are Xin Yi for girls and Jun Yu for boys.

Nearly four decades after the Speak Mandarin Campaign was launched in 1979, dialect given names have fallen out of favour.

In the 1980s, parents were encouraged to give their children hanyu pinyin names, which were used in schools. But there were many who preferred not to, so as to avoid the confusion of parent and child having different surnames.

These days, many young Chinese Singaporeans have names that comprise a dialect surname, a pinyin given name and a Western name, such as actor Aloysius Pang Wei Chong.

Geomancer Chen Yiming from Jing Zi Long Fengshui Centre said that parents are increasingly drawn to unconventional Western names, such as Jayden. The name, which is popular in the United States, has Hebrew origins and was featured in a 1994 episode of Star Trek. Jaden, the name of actor Will Smith's 19-year-old son, is a variant of this.

Other parents are inspired by Chinese television, with some naming their daughters after Ruo Xi, the lead character in popular drama Bu Bu Jing Xin (2011).

Some of lawyer Maurice Oon's young clients named themselves after South Korean idols such as Rain and "almost unpronounceable" nicknames that they used in gaming forums - which are so hard to recall that he could not cite any.

Mr Oon has also seen a "slight" increase" in Singapore-born Chinese who change their names as they do not want to be mistaken for Chinese immigrants, though some new citizens do this too. Usually, this involves adding a space between the last two characters, and replacing a pinyin surname with a dialect version: Zhang Haiming, for example, becomes Teo Hai Ming.

Associate Professor Lee Cher Leng from the National University of Singapore's Department of Chinese Studies has spent the past few years teaching a module titled "Bridging East and West: Exploring Chinese Communication".

"We are at the crossroads of East and West," she said. "Some of my students, who have Western names, also have Chinese names that were picked through fengshui."

She said that about 40 per cent of the 350 or so students who took her module this year have Western names. About 7 per cent have names with traditional dialect romanisation.

She has also seen more students with Western names, and Chinese names that echo or complement the sound of these Western names. For instance, Anna Yeo might simply be "Yang An Na" in Chinese.

A "surprising" 27 per cent of her students were named after their parents had consulted geomancers.

Today, geomancers who offer naming advice based on a person's birth profile, or bazi, are still very much sought after.

Huaxia Taimaobi Centre, for instance, has seen a 5 per cent yearly increase over the past five years in the number of parents asking for help with baby names.

Geomancers suggested two reasons for this continued demand - first, people are more careful when it comes to choosing names for the few children they have, and second, young parents are now less proficient in Chinese.

For example, at Huaxia Taimaobi Centre, many clients cannot write their Chinese names without first checking their identity cards, a spokesman said.

Geomancers there, and those at Way Fengshui Group, told The Straits Times that a small number of Chinese - about 5 per cent of their clients - still consult their family genealogy books, also known as jiapu or zupu.

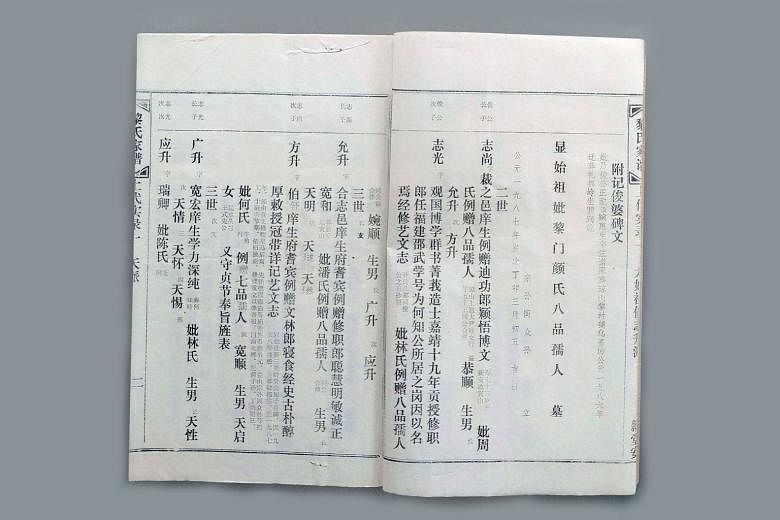

These books, which typically begin with the ancestor who first settled in a place and started his family there, track the lineage and history of clan members and record their achievements.

Many of them contain generation poems, whose successive characters become the successive middle characters, or generation names, shared by all in each generation.

Most Chinese names have three characters: one for the surname, followed by two for the given name.

In Singapore, Hainanese and Foochow people are more likely to consult a jiapu, possibly "because they are more tight-knit and traditional, given that they are the smaller dialect groups", Prof Lee said.

Retiree Loi Boon Lim, 68, hails from one such Hainanese family, whose members' middle characters are taken from a 30-character generation poem written by a family scholar around the middle of the Ming Dynasty. With allusions to scholarliness, virtue and valour, it spells out the Loi ancestors' aspirations for their descendants.

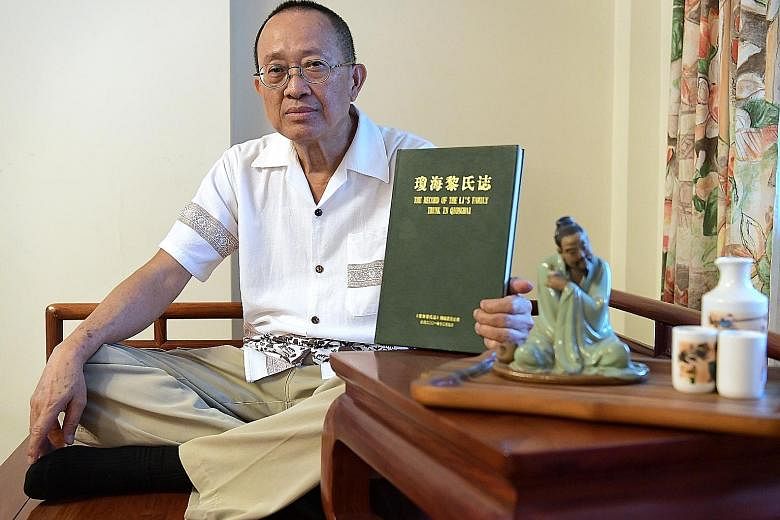

Mr Loi, the eldest son in his family, possesses a string-bound, typewritten jiapu compiled in the 1980s. "In Qionghai, Hainan, there are nine branches of Lis. Each branch has one family poem. My family belongs to just one branch."

Mr Loi belongs to the 32nd generation of Lois descended from ancestors who settled in Hainan Island in China. While the poem continues till the 46th generation, his family might switch over to another poem from the 37th generation onwards: In the late 1980s, the Lois in Hainan Island came up with a new 50-character poem, which Mr Loi describes as "an ambitious plan to standardise the whole Hainan Island".

In China, many families have lost their links to their jiapu, which were destroyed during the Cultural Revolution. In Singapore, some families stopped following it after converting to Christianity.

Unlike Mr Loi's family, the names of the men in Mr Khoo Yik Lin's family come from a four-character Chinese idiom. The middle characters for four generations of men in the Khoo family, when strung together, form the saying yan nian yi shou, or "increase longevity".

Mr Khoo, 42, a senior director in the social sector, has four-year-old twin boys Shou Wen and Shou Wu, and a seven-year-old daughter Hui Ning. Since shou is the last character in the saying, he said that as the next patriarch, he will have to pick a new saying.

Prof Lee's student Yeo Ze Wei Sean, 24, said his family stopped following the centuries-long jiapu naming tradition after his great-grandparents died. Mr Yeo, who is descended from wealthy Chinese merchants, said his great-grandfather used an alias that was closely associated with the shops he owned in Malaysia.

Mr Yeo, who is proud of his Teochew roots, wants to give his future children dialect names as a way of preserving tradition. "A person without history has nothing to hold on to. There's no anchor."

Fewer changing their names in IC

Fewer people in Singapore have been changing the names on their identity cards in recent years.

Between 2014 and last year, the Immigration and Checkpoints Authority of Singapore approved about 4,400 name changes on identity cards each year - down from 6,000 changes a year between 2011 and 2013.

Law firms said they observe a growing demand from certain groups of people who want to change their names through a legal document known as a deed poll.

For instance, lawyer Eben Ongsaid in the last five years, his firm has seen a 10 per cent to 20 per cent increase in the number of children having their names changed.

There are parents - across all races - who get their children's names changed before they get their identity cards, when they are about 15, he said. About 20 per cent to 30 per cent of his clients are below 21.

Lawyer Maurice Oon said about half of his deed poll clients these days are below 25. About three years ago, it was about 25 per cent.

Common reasons for name changes include a desire to add Western names to official names, fengshui, and parents getting divorced. And parents may now be more aware that they can change their children's names, Mr Ong added.

Since 2014, there has been a 10 per cent increase in the number of people replacing their Chinese given names with Western ones, Mr Ong said.

There has been another trend: an uptick in the number of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender or LGBT people who are getting their names changed.

Mr Ong's law firm has seen a10 per cent increase in such cases over the past five years.

Meanwhile, lawyer Chan Su Ying, from W. M. Low & Partners, said her firm has seen a 20 per cent to 30 per cent increase over the same period in LGBT people changing their names to ones that better reflect their sexual orientation.

A person with a Christian female name, for instance, might change it to something that is less gender specific, like "Sky", she said.