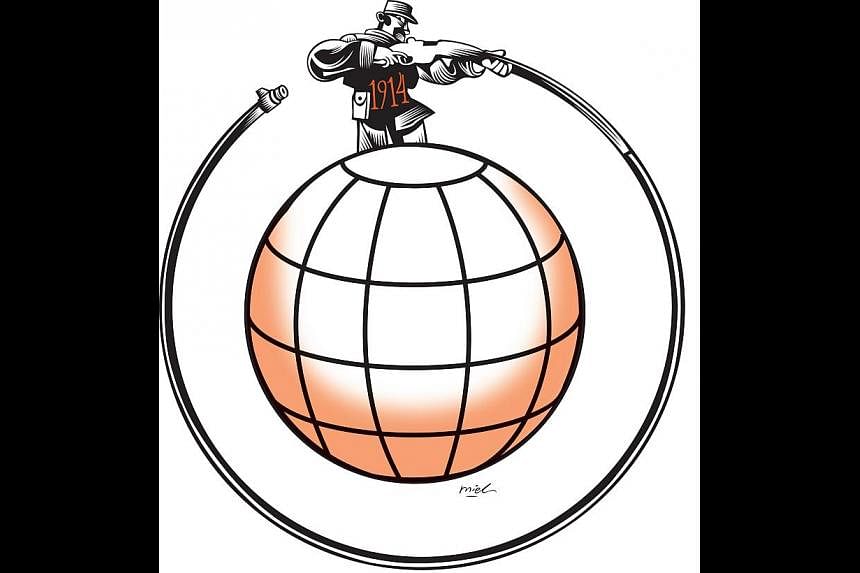

Precisely 100 years ago this morning, Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia. At first sight, just a confrontation between a decrepit empire which was already breaking up, and an impoverished, small Serbian state on the southern edge of Europe whose most substantial exports at that time were banditry and terrorism.

But Austria-Hungary's war declaration unleashed an avalanche of others. Within a week, most of Europe and its colonial dependencies - including Singapore - marched into battle. And, a few years later, so did the rest of humanity.

World War I not only claimed the lives of an estimated 10 million soldiers plus a further 20 million civilians, but it was also instrumental in creating the conditions for World War II with all its butchery in which at least another 100 million perished.

The way a string of small-scale and seemingly irrelevant diplomatic spats during a hot European summer of 1914 unleashed the biggest conflagration the world has ever known should, by now, be a subject best left to historians. Yet, the drama which began a century ago is still deemed to offer grim warnings to today's world leaders, particularly those in Asia.

Similarities today

AND for good reasons since, at least superficially, the tensions in Asia now appear to almost exactly replicate those in Europe a century ago. Like Europe then, Asia now is a continent in which some countries are rising fast and demand respect, while others are declining just as rapidly, and are desperate to cling to their previous importance, precisely what pushed the Europeans into war in 1914.

Like Europe, Asia is also afflicted by a variety of territorial disputes, each small and seemingly insignificant, but when seen in a broader context, all generating a climate of insecurity.

As the Europeans were in 1914, the behaviour of many Asian governments today is driven by powerful nationalist trends and a strong determination to avenge perceived historic injustices committed decades if not centuries ago.

And, like in Europe a century ago, an arms race is unfolding, while efforts to create regional security structures are largely unsuccessful. Although Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe raised many eyebrows earlier this year when he publicly warned about a repeat of a 1914 situation, the reality is that the dangers he highlighted cannot be simply waved away.

Still, if Asia is to draw useful lessons from Europe's tragedy a century ago, it will need to go beyond just such superficial comparisons. And the picture which emerges from a deeper analysis is both more encouraging and more ominous for Asia today.

First, the positive ledger: Asians now are mentally very different in almost every conceivable way to the Europeans of 1914. Although the world's economic powerhouse a century ago, Europe was still a continent in which nations remained utterly deferential to their superiors: Soldiers marched to their deaths because kings, princes or dukes told them to do so, and those wounded meekly accepted that they would receive treatment in hospitals in which officers were still separate from soldiers.

The soldiers who marched into battle in 1914 were also able to tolerate the unspeakable horrors which followed - months of eating stale bread mixed with mud in rat-infested trenches full of dead bodies - because the civilian lives of many of them before the war were not much better; they did not expect much out of life, and life did not offer them much either.

Furthermore, although literacy rates were high in Europe a century ago and newspapers were widely read, ordinary life was still national rather than global: Most Europeans had no idea what their neighbours were saying or thinking, and no reason to question the blind belief each nation had in its own justice. "Nations slithered over the brink into the boiling cauldron of war without any trace of apprehension or dismay," recalled British prime minister David Lloyd George years after the catastrophe.

Peace as an exception

BUT perhaps the most important difference between Europe then and Asia now is the intellectual context. For the Europeans of 1914, peace was not seen - as it is today - as the normal state of affairs, but as an exception; the normal state of affairs was that nations either constantly fought wars or prepared for them.

The youth in Europe a century ago craved war and rushed to volunteer. For the young men of that time, World War I was initially greeted with relief, with hope that the old, bourgeois and smug society into which they were born was about to be shattered. The war, in the language of patriotic writers at that time, was a "cleansing experience", just like rain after a hot dusty day.

In vain did a few older politician warn against the impending massacres, for they were dismissed as just idiots. Europe's rush to war in 1914 proved right Lord Melbourne, the 19th-century British premier after whom the Australian city was named, who once famously remarked that nations sometimes encounter decisions when "all sensible men are on one side, and all the damned fools are on the other, and the damned fools are right".

Compared to all that, Asia today cannot be more different. Even those hotheads who may wish to settle historic grievances by force know this will not be a picnic. Nobody believes that wars are a "cleansing" experience. And although quite a few Asians may worry about the supposed revival of a "militaristic" Japan, nobody truly believes the Japanese are about to lay down their iPads or smartphones and don uniforms to march to war. Asia's bureaucratic status quo is not being challenged by a culture of death and self-destruction. The chances of Asians relishing a military pile-up are, therefore, mercifully slim.

Lessons from 1914

STILL, there are other lessons from Europe's 1914 disaster that remain ominously applicable to Asia today. The first is the fact that growing economic links do not guarantee peace. Europe's nations were closely tied together in trade, and all its ruling monarchs were inter-related; the bonds were so strong that Norman Angell, a British journalist, won acclaim and a Nobel Prize for his thesis that Europe would never again go to war. His book was published in 1910; a few years later, Europe went up in flames. Those who argue that trade inter-dependence between Asian countries must mean no wars are well advised to read Angell's old discredited book.

But there is another lesson from 1914 which applies even more to Asia today, although it is seldom mentioned. It involves a comparison between the position of Germany on the eve of World War I, and that of China today. Like China now, Germany then was a fast-rising power, whose future ascendancy seemed unstoppable. While Britain - the world's superpower at that time - produced about twice as much steel as Germany during the early 1870s, by 1914, Germans were producing more than twice as much steel as the British. Moreover, only one-third of German exports in 1873 were finished goods; the portion rose to 63 per cent by 1913, overtaking Britain in trade.

In short, Germany did not need to go to war in 1914; if it just kept to what it was doing best, Germany was destined to dominate Europe through peaceful means, and probably by the 1920s.

So, why did Germany rush into battle? Essentially, because its leaders encouraged an aggressive nationalism at home which ended up limiting their room for diplomatic compromise, and partly because its military commanders were not subjected to any public accountability, and therefore designed war plans with little understanding of the world outside Germany, or the implications of what they were doing.

Germany's generals believed, for instance, that Britain would not join World War I, a catastrophic mistake which would not have happened if German officers consulted any outside experts.

Chinese officials will, no doubt, dismiss any comparison with Germany in 1914 as mischievous. But a similar isolation from debate or scrutiny which German military planners enjoyed a century ago applies to China's People's Liberation Army officers today. And a similar, aggrieved nationalism which Germany suffered from in 1914 is being tolerated in some Chinese quarters today.

Of course, Germany alone was not responsible for unleashing World War I; its neighbours which tried to isolate and corner it, must share responsibility.

And the same applies to China: Its behaviour will be influenced by what others in Asia or outside the region do.

Nevertheless, the danger of another 1914-style disaster remains, even if the backdrop is different and the continents are different. For, as the British historian AJP Taylor once noted: "We learn from history not to make the old mistakes, and that leaves us free to make different ones."