FOR scholars who study the phenomenon of political religion, the news that former head of Egypt's armed forces Abdul Fattah al-Sisi has declared the Muslim Brotherhood movement would "cease to exist" if he is elected president of that country is an ominous reminder of the past.

The previous government of Egyptian president Mohamed Mursi made several serious mistakes and policy errors - not least of which was a failure to seek pragmatic and workable alliances with other non-Islamist sectors of Egypt's complex plural society. But the nature of Mr Mursi's downfall following a coup in July last year and the violence that preceded and ensued from it have raised concerns across the globe.

The country is currently being run by an interim government. The presidential election is due to be held next Monday and Tuesday.

Mr Sisi's stated intention of wiping out all traces of the Brotherhood from Egypt beggars belief. The Brotherhood is the biggest organised movement in the country. Any attempt to wipe it out would entail a confrontation on a scale that is unprecedented in modern Egyptian history. What is more, the impact of such a move would be felt elsewhere too.

Egypt's importance

HOW and why would such events in Egypt have far-reaching consequences for the rest of the world? Well, for starters, it ought to be noted that Egypt is the most populous Arab country, with an outreach that extends well beyond its borders. Egypt's centres of religious learning have been magnets that have attracted hundreds of thousands of scholars from all over North Africa, the Arab states, South and South-east Asia. From Morocco to Indonesia, thousands of young men still dream of getting a place at prestigious religious universities such as al-Azhar in Cairo.

This is due to the enormous amount of cultural capital that has been accumulated by the religious schools of Egypt such as al-Azhar, and the tremendous prestige that is associated with a degree (ijazah) from that institution. It is not an overstatement to say that al-Azhar today ranks as the "Oxford of Muslim religious seminaries across the world", and for an ordinary religious student from a country like Pakistan or Indonesia, a degree from al-Azhar has value that cannot be measured in monetary terms alone.

And it is there - smack at the centre of Cairo's cityscape - that these foreign students get their first close glimpse into the realities of life in modern-day Egypt.

During the troubled period when the previous government was tottering on the verge of collapse and Cairo was overwhelmed by demonstrations, governments from all across the Muslim world were forced to come up with contingency plans to evacuate tens of thousands of students who were studying in the country. This tells us something about how highly Egypt ranks in the eyes of millions of people the world over.

Current developments in Egypt are being watched closely by scores of Muslim religio-political movements across the globe, whose sympathy for the Muslim Brotherhood may range from friendship and sympathy to all-out committed support and devotion.

Parties such as the Jama'at-e Islami in Pakistan and Bangladesh, Parti Islam SeMalaysia in Malaysia and the Prosperous Justice Party in Indonesia have been updating their websites and party newsletters with newsfeeds about the goings-on in Cairo.

They have voiced their disapproval of Mr Mursi's ousting too.

In the global age that we live in, it is safe to conclude that whatever plans Mr Sisi may have for the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt would be known to the rest of the world as well.

Politics of confrontation

THE real concern, however, is that the posture all sides have been taking of late is one which is decidedly confrontational, and of a zero-sum character. It leaves no room for compromise, dialogue or resolution. This has raised the stakes in the confrontation to the level of an existential crisis. Each side has to battle it out to the bitter end against the other. No quarter will be asked or given.

Just how such a confrontation can take place without incurring a massive human cost is the worry of many analysts. They see the situation as the beginning of an extended bitter conflict that will blight not only the social landscape of Egypt, but may also have wider ramifications for the rest of the Muslim world as well. Should the Muslim Brotherhood of Egypt be wiped out and reduced to "non-existence" as Mr Sisi has promised, there is the very high likelihood of protests across the Muslim world by those who see the movement as their ally in a wider global struggle.

What began as an internal political conflict in Egypt may develop into something with wider global ramifications.

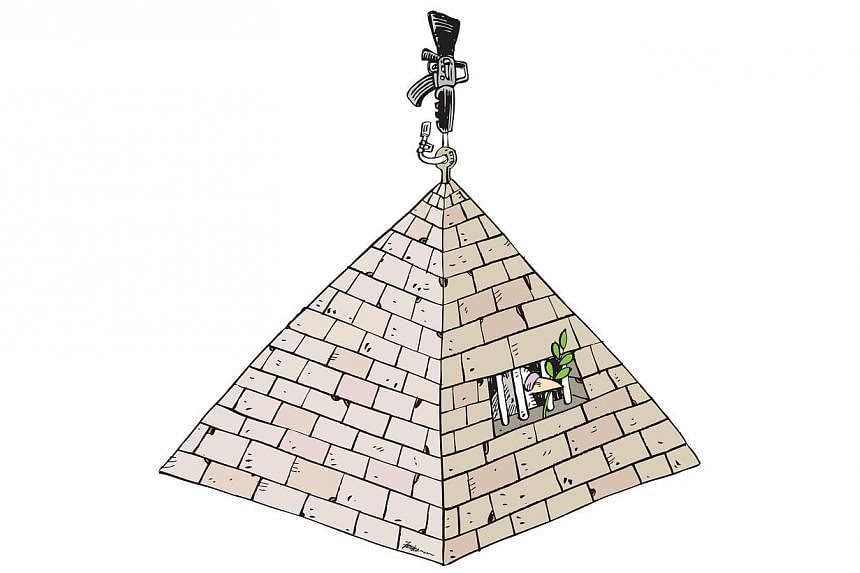

Egyptian history has shown that in such instances, where dialogue is superseded by confrontation, victory goes to the side that uses the most violence. This has not, however, made life in Egypt any better or safer for anyone. In a situation where violence is normalised - and worse still, justified via appeals to God or the nation - then violence itself becomes the mode of conduct and the thing that defines the identity of the actors concerned.

Former president Hosni Mubarak's muscular nationalism was expressed in terms that were as stark as they were fearsome. Likewise, the reaction of radical groups opposed to the Egyptian government, such as the Takfir wal Hijra, was to the point, and expressed via the gun or the bomb.

No middle ground

THE net result of successive decades of state violence and Islamist counter-violence has been the erosion of the liberal middle ground. Moderates have been silenced and intellectuals marginalised. This has led to the creation of a society living in a state of perpetual terror. In a climate of constant violence, where violent acts replace the vocabulary of dialogue, violence itself became a means of communicating a message.

In such a state, we might as well forget the idea of developing and expanding a moderate middle ground, for liberals do not thrive when shots are being fired in all directions around them.

We must also remember that nothing radicalises ordinary citizens faster and more effectively than the perception - real or imagined - that they are the victims of an oppressive state which does not discriminate in the manner that it metes out its violent justice. The best example of this is found in the biography of one of Egypt's most famous (or infamous) sons, Sayyid Qutb. He began his career as a simple, unassuming school teacher - until his experience of being put on trial and later imprisoned under the regime of Gamal Abdel Nasser in 1966.

It was his first-hand experience as a victim of the Nasser regime that turned Qutb away from the promises of Egyptian nationalism to a more radical understanding of religion as a counter-hegemonic discourse that could be used against the state. Qutb's time in jail transformed him completely. It was within the confines of his cell that he felt the crushing weight of the state fall upon his shoulders.

The challenge that lies before Egypt today is to come up with some means that will stop this vicious downward spiral. All too often, radical challenges to state power can be and are met with a violent state response, and this, in turn, feeds the flames of radical activism even more.

The root of the problem lies in Egypt's income and wealth differentials, the breakdown of its state institutions, the loss of trust in the political elite and the disillusionment with the nationalist project. These were the factors that turned the people away from the nationalist government in the first place during the Arab Spring. These issues still need to be addressed in a manner that brings together the collective energies, ambition and intelligence of the Egyptian public as a whole.

Failure to address the root causes of public unrest - which lie in the domains of governance, administration, economics and education rather than religion - may perpetuate the violent dialectic that pits secular nationalists against Islamists.

If anyone believes that bellicose rhetoric against the Muslim Brotherhood will solve the problem, they should think again. Many anti-state movements rely on oppression and persecution to drive them further. One is reminded of the quote attributed to Iranian leader Ayatollah Khomeini: "The road to the revolution is paved with the bodies of martyrs."

This has proven to be the case for die-hard revolutionary movements like the Maoists in India and the Irish Republican Army of Northern Ireland, and it has been the case for the Muslim Brotherhood of Egypt as well. History does have its uses, but only if we remember not to repeat the mistakes of the past.

The writer is an associate professor at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University.