I remember the gardener. They called him Abu Ward, Father of the Flowers. He ran the last garden centre in East Aleppo, an oasis in a war-torn city to which people retreated to quench their thirst for life and beauty in the midst of death and destruction.

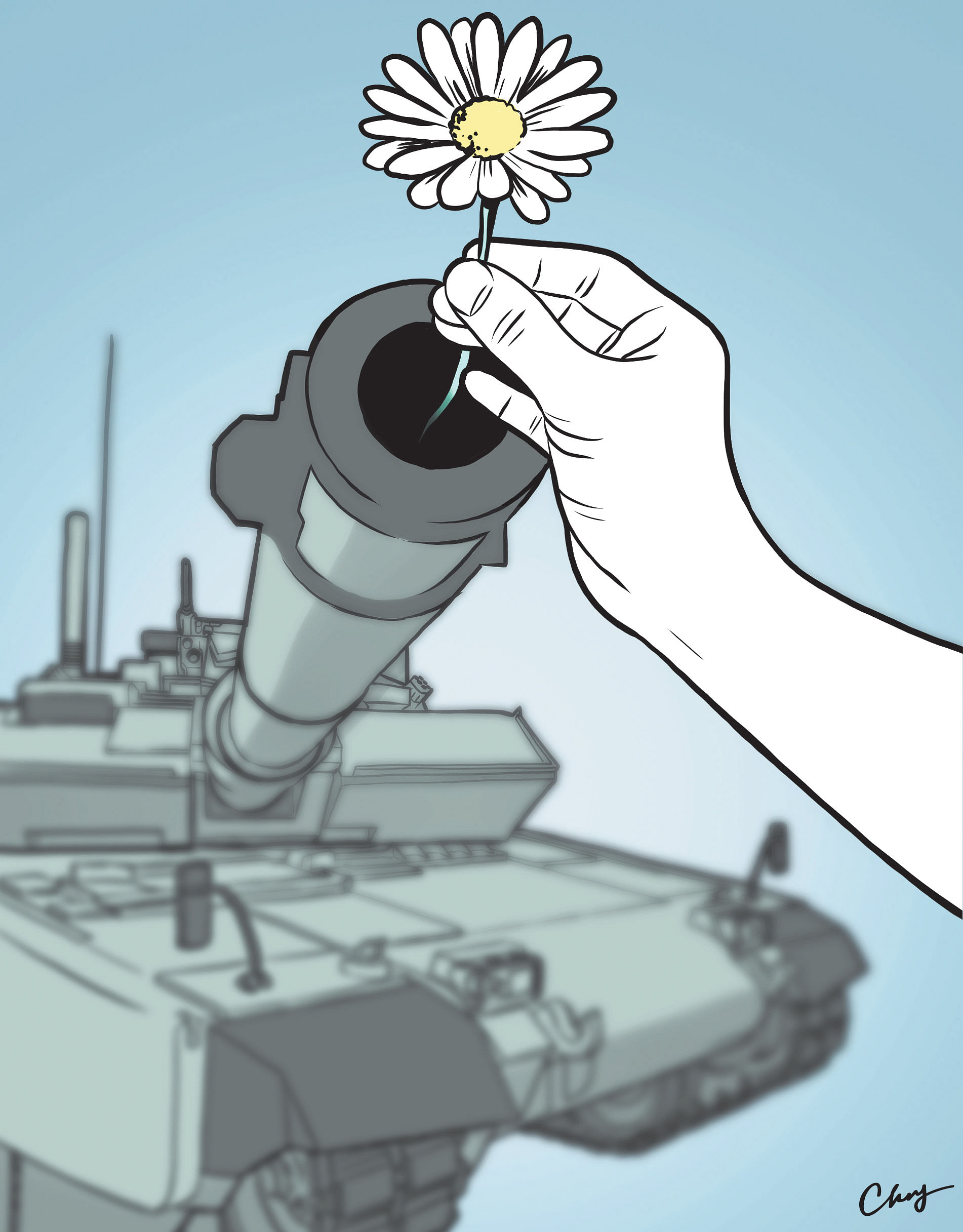

He gave residents a way to bring life back into their city, as some did by buying pots of plants to place at roundabouts. It was their way to both resist their aggressors and rebuild their home.

"Flowers help the world," Abu Ward, a gruff weather-beaten man, said in a short video clip produced by Channel 4 News and circulated on social media. "There is no greater beauty than flowers... and when you smell them, they nourish the heart and the soul."

Six weeks after filming began, he was killed by a bomb that fell near his garden centre. His 13-year-old son Ibrahim, who quit school to work with his father, wiped away his tears as he told an interviewer he did not know what he would do.

I felt a connection because I too love plants. When I watched Abu Ward water his plants and gently caress one in particular that had been hit by shrapnel but was still alive, I recall the joy of seeing new shoots sprout from my ferns and begonias. And like Ibrahim, I love talking to my father, a keen gardener, about our plants - those that are flourishing and those that need help.

But in all other ways, I have so little in common with the people of East Aleppo where a humanitarian crisis is deepening, five years into Syria's brutal civil war. From news reports and social media, I know civilians, including children, are dying every day but their suffering seems so remote and removed from my reality.

New York Times columnist Thomas L. Friedman called this the divide between the world of order and the world of disorder, and he was pessimistic about the chances of big powers like the United States, Russia and China working together to stop the spread of disorder. "That is certainly necessary. But the prospects for that are limited," he wrote in 2014. "No power these days wants to lay hands on the world of disorder because all you win is a bill. And even if they did, it would not be sufficient."

For Syrians of course, the world's indifference inflicts a wound on their psyche both deep and raw. Take writer Samar Yazbek, who lives in exile in Paris but who returned to Syria three times after the start of the war to document her countrymen's suffering. What she witnessed during those trips is the focus of her award-winning 2015 book The Crossing: My Journey Into The Shattered Heart Of Syria.

In the book's epilogue, she writes: "The outside world won't believe that what is happening in Syria - which the whole world is witness to - is nothing but the international community's desire to see its own salvation. Other people are dying instead of them. Something prompts their desire to track life as it is extinguished before their eyes. They are the survivors and that's enough...

"What is happening is nothing new in the history of humanity, but now it's unfurling in public view, the blood spilling before our eyes and onto our hands. With savage images that make cold-hearted monsters of us, the global media machine churns out a barbarous conveyor belt of updates that ensures each victim is forgotten as soon as the next one comes along, breeding a nauseous familiarity through the magnitude of death. We consume the news, then toss it out with the rubbish."

The Financial Times' chief foreign affairs columnist Gideon Rachman put it more succinctly, though he was no less damning. In a column published late last month and headlined "We are all Stalinists on Syria", he quoted the Soviet dictator's statement, "A single death is a tragedy, a million deaths is a statistic" and added: "When it comes to the war in Syria, the West has been living by Stalin's dictum. So has the rest of the world."

What can restore our sense of shared humanity? I must confess that even reading Ms Yazbek's book was too difficult for me. It was page after page of heart-wrenching witness accounts about mothers weeping as their teenage sons were taken from them and executed, their daughters raped in their homes; of families struggling to make it through each day as snipers shot at them and bombs fell on them from above.

After two chapters, I stopped reading.

Yet I know that change can only come from within each human heart, and that solidarity is possible. It is the demand that we treat one another as brothers and sisters.

Syria is not the only place on earth where there is human suffering on a large scale. In various parts of Africa, people are dying in civil wars or starving as a result of famine or stuck in refugee camps that have become like prisons.

How can we bridge the yawning gulf between their world of disorder and our world of order? It must begin with a desire to do so, and such a change of heart comes about as a result of a personal encounter with the other.

Ten years ago, I went to Kolkata and experienced deep culture shock. It was the closest I had come to the world of disorder. After two hours there, I wanted to take the next flight back to Singapore. But I stayed and saw first-hand the chaos and poverty on the streets of that great city. There were many families living on the streets - bathing, cooking, eating and sleeping out in the open. Later, I realised that waves of refugees had fled to Kolkata in the wake of the Partition of 1947 which divided the British province of Bengal between India and Pakistan, and the subsequent Bangladesh Liberation War of 1971.

I do not know if any of those families I saw will ever have a home of their own. When confronted with the course of history beyond our control, our sense of inadequacy may flow into apathy. But while that may be the most likely response, it is not the only one possible. Kolkata was after all where Mother Teresa began her work of caring for the poorest of the poor, a mission that has left a profound effect on the world.

That is why I find the words of Bill and Melinda Gates, in their 2014 Stanford Commencement speech, both moving and apt. They chose as their theme optimism, because at Stanford "there's an infectious feeling that innovation can solve almost every problem", Mr Gates said.

They went on to describe various seemingly hopeless situations they had encountered in their travels to Africa and India for their philanthropic work, and their conversations with families mired in poverty, with sex workers and Aids sufferers.

"When I talk with the mothers I meet during my travels," Mrs Gates said, "I see that there is no difference at all in what we want for our children. The only difference is our ability to give it to them."

She reflected on the role of luck in her family's success: "When were you born? Who were your parents? Where did you grow up? None of us earned these things. They were given to us.

"When we strip away our luck and privilege and consider where we'd be without them, it becomes easier to see someone who's poor and sick and say, 'That could be me'. This is empathy; it tears down barriers and opens up new frontiers for optimism."

She ended their speech with this appeal: "As you leave Stanford, take your genius and your optimism and your empathy and go change the world in ways that will make millions of others optimistic as well.

"You don't have to rush. You have careers to launch, debts to pay, spouses to meet and marry. That's enough for now.

"But in the course of your lives, without any plan on your part, you'll come to see suffering that will break your heart. When it happens, and it will, don't turn away from it; turn towards it. That is the moment when change is born."