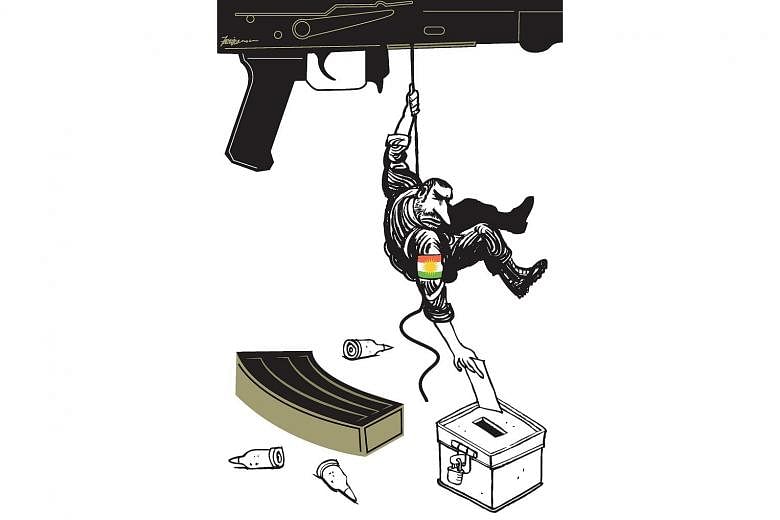

LONDON • In a Middle Eastern region where nations seldom agree on anything, there is now an almost universal consensus on one matter: that the independence referendum which the Kurds of Iraq plan to hold today amounts to a highly dangerous step which should have been stopped at all costs.

And major global powers agree. "Provocative and destabilising" is how the White House described the referendum; a process with "no prospect for international legitimacy" is how European governments characterise the vote.

Yet the Kurds are unlikely to be deterred, for they have spent a century defying poor odds to their survival. A new Kurdish state may not be the most immediate outcome of the referendum, but further instability in the Middle East is virtually guaranteed.

The Kurds are often referred to as the largest ethnic group without a state, although that is incorrect. Many distinct ethnic groups in Africa do not have a country of their own, as neither do the Tamils and Sikhs. Nor is it preordained that independent statehood is the only way an ethnic group can organise itself. And it is a fact that at least until the beginning of the 20th century and perhaps even later than that, most Kurds spent little time pining for independence.

But it is also true that the fate of the Kurds, a Muslim group with a distinct history and language and classified as being closer to the Iranian rather than the Arab people, was always considered far too important to be left to the Kurds themselves, and that their own aspirations for free expression and assertion were crushed at every turn.

The Kurds failed to get their own country when the Ottoman Empire, where the overwhelming majority of them lived, collapsed in 1918. They also failed to gain any special status when the European colonial powers withdrew from the Middle East at the end of World War II. In short, they are one of modern history's greatest losers, a fate often decried by a nation which reveres in its culture the fox, a creature admired for its cunning.

Their numbers are considerable - a total of 45 million worldwide. And their presence in certain countries is substantial as well: About 17 per cent of the population of Turkey and Iraq as well as about 10 per cent of the population of Syria and Iran are Kurds.

Still, a key reason for their persistent failure in establishing a state is that the Kurds are deeply divided between a number of countries, language dialects and historical experiences, and the states where they live obviously prefer to keep it this way. Although Iran and Iraq frequently used the Kurds as proxies in their wars, and Syria frequently hosted Kurdish armed gangs that wreaked havoc in neighbouring Turkey, just about the only matter which Turkey, Iran, Syria and Iraq always agreed on is that an independent Kurdish state will never arise, for the very simple reason that it could come about only at their territorial expense.

AUTONOMY, THEN REFERENDUM ON INDEPENDENCE

The fact that the independence referendum is now being staged in Kurd-controlled areas of Iraq is no surprise. For Iraq's Kurds both suffered grievously during the rule of former Iraqi president Saddam Hussein and were the chief beneficiaries from his overthrow.

The Kurdistan Regional Government has been operating its own autonomous area for a decade, complete with its own military, the famed Peshmerga, its own Parliament and its own taxation system, as well as oil-exporting operations.

And although Mr Masoud Barzani, president of Iraqi Kurdistan, has been careful to avoid an outright demand for independence, everyone knew all along that this was his ultimate objective; he was merely biding his time, carefully nurturing his image as the West's most solid regional ally, while strengthening his lobbying efforts in the United States and tightening his political control at home.

Western governments have tried to persuade him to continue down that route by creating all the trappings of a state, without acquiring the formal status of independence. Yet this time, Mr Barzani, a wily operator, has decided otherwise, for a variety of reasons.

First, he knows that if he does not make a dash for independence now, the chance is unlikely to return in the near future. For the Middle East is currently paralysed by many interlinked conflicts that have no obvious solution. These include Iraq's and Lebanon's own existential domestic crises, as well as the irreversible disintegration of Syria, the confrontation between Iran and most Arab nations, rows between Gulf nations and the quest of Turkey to become a regional power.

Add to this the curious strategic absence of the US as the region's arbiter and the return of Russia as a player, and it is obvious that the Kurds - like many other groups in history - are keen to seize their chance for independence while all others are far too busy to do much about it.

There are also more parochial calculations. Mr Barzani's constitutional term of office has long expired, and there is nothing better for him to shore up his legitimacy than flying the flag of independence, particularly since this follows his controversial suspension of the Kurdistan National Assembly, the local Parliament.

Either way, it is clear that the Kurds of Iraq cannot be persuaded to give up their referendum today. And it is equally clear that the result will be a massive "yes" to independence.

What the pressure of Western governments has achieved is to extract a promise from Mr Barzani that the vote will not trigger any formal mechanism for independence; it will merely give Mr Barzani a mandate to launch negotiations with Baghdad for an eventual separation. But that, in itself, could still plunge the Middle East into further violence.

THE THREAT OF A VIOLENT RESPONSE

To start with, there is no agreement on where the borders of Kurdistan should be drawn. The referendum is being held in no less than 15 different contested areas, including the ethnically mixed city of Kirkuk which the Kurds demand because of its oil riches, but where they are a minority.

Yet even if Kirkuk is ultimately excluded from Kurdistan, the eventual emergence of a Kurdish independent state will transform the Middle East. The danger that Turkey and Iran will join hands to crush this newly independent entity is exaggerated because, while Ankara and Teheran are currently making threatening noises, their strategies are likely to be very different.

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has sought to befriend Iraq's Kurds in the hope of keeping them separate from Turkey's own Kurds and the Kurds of Syria, while Iran proved more interested in consolidating its hold over the rest of Iraq than in upholding Iraq's territorial integrity.

What will happen instead, however, is much worse: Another proxy battle in the Middle East, with Kurdistan at its epicentre. Provided that Kirkuk is not incorporated into a future Kurdistan, Turkey will try to smother the new state with love, by offering it transit routes for its oil exports, in the hope of making it a Turkish satellite.

Meanwhile, Iran will concentrate on making what remains of Iraq into a Shi'ite satellite. And in response, Israel - whose military has had close if secret relations with the Kurds since the 1960s - and a Saudi-led Sunni Muslim bloc will try to establish good relations with an independent Kurdistan in the hope of using it as a lever against Iran and an Iranian-leaning Iraq, as well as a battering ram against greater Turkish involvement in the Middle East which all Arabs resent.

The US and other Western nations cannot stop this process, but they can mitigate its baleful effects by concentrating on improving an independent Kurdistan's governance.

For much of the propaganda about an Iraqi Kurdistan that is supposedly better organised, Western-leaning and liberal by including women in all its administrative branches is just that - propaganda.

The reality is that an independent Kurdistan starts its life like most other Middle Eastern countries - with a dysfunctional political system, an economy utterly dependent on oil, high corruption and poverty, as well as low education levels.

The real task, therefore, should be to avoid the emergence of another potentially failed state and to limit the violence that will ensue. For it is too late to keep the existing borders of the Middle East intact. And it is too late to admit that, if the nations of the Middle East wanted to avoid the emergence of an independent Kurdish state, they should have adopted different policies decades ago.