And so, the campaign for Britain to remain in the European Union has been lost. It was one of many uphill battles that the late British Member of Parliament Jo Cox, a former activist campaigner and humanitarian aid worker, fought in her 41 years.

I wonder if she ever tired of swimming against the tide.

I wonder if, in the face of vast apathy about the plight of Syrian civilians and refugees, whose cause she championed, or when she became the target of threats and hate speech from fellow Britons who disagreed with her views on immigration, or when confronted with the failings of the political system and the feet of clay of political leaders she worked for and admired, she ever thought of throwing in the towel and giving up.

After all, she could have retreated to a domestic cocoon of loving husband, two children, supportive parents and sister; and, with a degree from the University of Cambridge, chances were she could have secured a job that paid her a decent income and left her with more time for family and leisure.

What kept her going - despite disappointment? What drove her to keep speaking up, to keep campaigning for those with no voice of their own, to remain faithful in the service of those in need, regardless of nationality, race or creed?

Those questions arise for many who choose public service over personal comfort, and that includes Members of Parliament here who have made personal sacrifices to serve Singapore.

The outpouring of grief and grace that followed Ms Cox's death just over a week ago provides a vital clue. Of all the praises heaped on her after she died from injuries sustained in a violent attack, one phrase stood out - woman of moral purpose. That was how one of her constituents in the West Yorkshire town of Batley and Spen described her.

I wonder how many citizens of democracies would use those same words to describe the men and women elected to represent them, or for that matter, their political leaders? In the varied responses to Brexit that came through my Facebook feed last Friday, I was struck by one that decried this age "dominated by spineless politicians with neither vision, conviction nor judgment".

Ms Cox herself had expressed disappointment at the lack of moral leadership on Syria by those who led America and Britain. In a speech to the British Parliament last year, she said: "While I am a huge fan of President (Barack) Obama - indeed, I worked for him in North Carolina in 2008 - I believe that both he and the Prime Minister (David Cameron) made the biggest misjudgment of their time in office when they put Syria on the 'too difficult' pile and, instead of engaging fully, withdrew and put their faith in a policy of containment.

"This judgment, made by both leaders for different reasons, will, I believe, be judged harshly by history, and it has been nothing short of a foreign policy disaster… I do not believe that either President Obama or the Prime Minister tried to do harm in Syria but, as is said, sometimes all it takes for evil to triumph is for good men to do nothing."

Her response was to restart a cross-party parliamentary group devoted to Syria and its suffering people. All very well perhaps for a humanitarian aid worker-turned- backbencher MP to be fired up by moral purpose, you say, but is it realistic to expect the same of political leaders with economies to run and strategic interests to defend?

Take Brexit as an example. The notion of moral purpose has, if anything, been noticeable by its absence. A non-issue to bankers and those hoping to make a quick buck off Friday's result, but to those with an understanding of the ideals that gave birth to the European project, it was a source of deep disappointment. A "sad failing on the part of the 'in' campaign" was how Mr Ben Ryan put it, in a commentary published in January by The Guardian and bearing the headline "The 'in' campaign fixates on business - what about Europe's moral purpose?"

Mr Ryan, author of the report - A Soul For The Union - for the religion and society think-tank Theos, recalled that "at the beginning there was a moral mission at the heart of Europe - a desire to seek peace, and the successful reconciliation of France and Germany (after WWII)", as well as a desire to improve work conditions and the lives of citizens through the building of a welfare state and protection of workers' rights.

Indeed, the late Jean Monnet, the man most associated with the European project, had but one objective: "Make men work together, show them that beyond their differences and geographical boundaries there lies a common interest."

If those words sound vaguely familiar, it may be because Ms Cox said something similar in her maiden speech in Parliament, in words that have been widely circulated online since her death. Celebrating the diversity in her constituency, she said: "Our communities have been deeply enhanced by immigration, be it of Irish Catholics across the constituency or of Muslims from Gujarat in India or from Pakistan, principally from Kashmir. While we celebrate our diversity, what surprises me time and time again as I travel around the constituency is that we are far more united and have far more in common with each other than things that divide us."

Mr Ryan acknowledged that "today's EU has not always done justice to its founders' vision". Pointing out its shortcomings, he wrote: "The mission for peace has been hurt by failure in the Balkans, and responses to the euro zone crisis have led to welfare states and working conditions suffering in many member states. The ambiguity is clear in responses to the refugee crisis, where the EU has struggled to broker agreement. For all that, the policies of the EU's most influential and committed pro-European leader, Angela Merkel, to take a disproportionate share of refugees have demonstrated a continuing commitment to the moral vocation of the European project."

Moral purpose is not the same as moralism. The latter implies judgmentalism and a drawing of lines between those who are good and those who are bad, of wanting to impose one's moral code on others and to exclude those who do not subscribe to the same way of life.

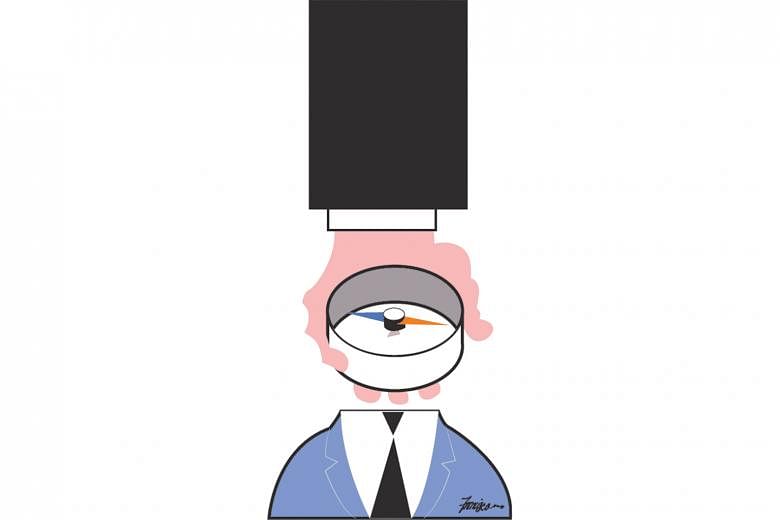

Moral purpose is altogether larger; it is "a value that, when articulated, appeals to the innate sense held by some individuals of what is right and what is worthwhile". That was the succinct definition put forth by Nikos Mourkogiannis in his article The Realist's Guide To Moral Purpose, for the website of the University of Chicago Booth School of Business.

"A moral purpose's effectiveness," he wrote, "also depends on its connection to the shared culture of humanity - to the extent that it draws on philosophical ideas that have stood the test of time. When no clear moral purpose is articulated, a company acquires a de facto amoral purpose: expediency. It becomes the kind of company that professes, 'We are here only to make money'."

If you ask me to sum up what moral purpose does for a company, for a country, for a politician, I would say it gives courage, the kind of courage Ms Cox had in spades.

Today's world needs courage to overcome the politics of fear and heal its divisions, and we need politicians of moral purpose to lead the way.