Two months into the Donald Trump presidency, it is clear that - whatever our personal misgivings about the personality and mannerisms of America's 45th President - we in Asia will have to live and work with President Trump.

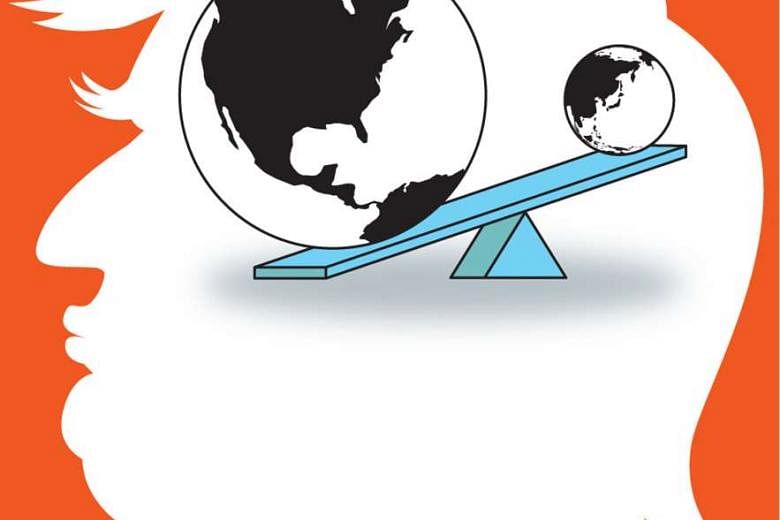

What matters most for our region, though, is not the polarising debate over his immigration ban, his Mexico border wall or even his tweets about Obamacare. Rather, what concerns us most in Asia is how Mr Trump conceives of and intends to pursue American interests in Asia.

After two months in office, it remains a challenge to divine elements of an Asia policy in this new administration. While key foreign policy positions in the Cabinet have been filled, there are hundreds, if not thousands, of positions across government departments that remain vacant. Indeed, until these officials are in place, it is impossible to obtain a clear sense of what American foreign policy is under Mr Trump.

There are, however, some early signs, and several observations can be made in that regard.

SECURITY AND FOREIGN POLICY

First, we should distinguish between words and deeds. To be sure, the world is seized with every word or tweet from Mr Trump. In keeping with this fascination, every offhand or ill-informed remark has been well documented and parsed. On the basis of words alone, the picture looked grim.

During the campaign, Mr Trump took a cantankerous line on China, although this is hardly unusual for United States presidential campaigns in more recent times (with the possible exception of Mr Barack Obama's). More alarming, however, were his comments suggesting reconsideration of America's security commitments to regional allies South Korea and Japan.

These were met with consternation, not only in Seoul and Tokyo, but also elsewhere in the region where the US had hitherto invested security equities and deepened defence relationships. And if these were not enough, receiving the phone call from the independence-leaning Taiwanese President, Ms Tsai Ing-wen, followed by capricious comments about possibly reviewing Washington's longstanding "one China" policy - the foundation for Sino-US relations for more than four decades - was positively distressing. The appointment of China hawks to key positions on trade and commerce added further to the adversarial climate.

Yet, after two months of the Trump presidency, the administration's approach to regional security is actually looking fairly conventional.

Relations with Japan were quickly placed back on an even keel, thanks in no small part to Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, who was quickest off the block in engaging Mr Trump to head off any chance of the US gravitating away from its traditional commitment to Japan.

Meanwhile, Secretary of Defence James Mattis made a successful visit to Tokyo, where he reinforced American commitment to Japan and to regional security, and to Seoul, where he reassured his hosts that the US would stand by them in the event of North Korean aggression.

Mr Rex Tillerson has just completed his first Asia tour - to Japan, South Korea and China - as Secretary of State, and Vice-President Mike Pence is expected to head here next month.

On relations with China, Mr Trump has pulled back from the brink and declared that his administration would abide by the US' "one China" policy.

All this indicates that people need not make too great a play of Mr Trump's tweets. This may be common sense - he is, after all, now a politician - but it is worth repeating.

Second, set aside his antipathetic tone and we realise that Mr Trump's call for America's allies to assume a greater share of their security is hardly new. In their own ways, Presidents Bill Clinton, George W. Bush and Obama also pushed for greater burden-sharing.

The simple reality is that the US can no longer afford to underwrite on its own the security of all its friends and allies. But even on that score, it is notable that, as senior Japanese diplomats involved in the meetings shared with me, Mr Mattis did not raise the subject of burden-sharing at all during his visit to Tokyo. Equally significant, there was no attempt by Mr Trump to question or undermine the messages that Mr Mattis sent on his trip to South Korea and Japan after the fact. If anything, Mr Trump reinforced Mr Mattis' message during his own meeting with Mr Abe.

Third, we need to recognise that insofar as national security and foreign policy are concerned, Mr Trump has surrounded himself with very strong and competent personnel, most of whom are in the mould of traditional national security and foreign policy senior officials.

Mr Mattis, Mr H.R. McMaster and Mr John Kelly are anything but yes- men. And while some are frustrated at Mr Tillerson's performance thus far, few doubt his professional qualities as a corporate leader. Simply put, if Mr Trump intended to have his way or bulldoze foreign policy through, he would have appointed a very different cast of characters. Of consequence too, amid speculation swirling around Mr Trump's approach to Moscow, is the fact that this key national security leadership possesses a sobering view on Russian President Vladimir Putin and Russia. This suggests that they are not likely to tolerate any capitulation of American interests to Moscow.

This is not to say that the waters ahead will not be rough. There are (at least) three caveats.

MORE CONFRONTATIONAL ON CHINA

First, the State Department - presumably the architect of foreign policy - has apparently been kept out of the loop on foreign policy discussions thus far in this administration. Part of the problem lies in the fact that while Mr Tillerson may be a veteran chief executive officer, he is inexperienced as a government policymaker and is still finding his feet. Add to this the fact that many senior appointments have yet to be made, and you have a department in drift.

Second, there is concern that Mr Steve Bannon, Mr Trump's enfant terrible chief strategist and adviser, has been given a place on the National Security Council. There is good reason for this apprehension, for Mr Bannon's appointment was an unprecedented move with disturbing portents, especially if he becomes a competing centre of power in national security policymaking.

Third, on China, this administration has signalled an intent to be more competitive - and confrontational, if necessary. Underlying this is the present administration's view that, while it shares with its predecessor the objective of stable Sino-US relations, they differ on how best to achieve this.

In the minds of many a Trump official, the Obama administration was too soft on China. The objective now is to achieve stability by digging in rather than ceding American interests and influence in the hope that China could be persuaded to change course on any given issue, which is their view on their predecessors' China policy. This will likely be the new normal in Sino-US relations that Beijing and the rest of the region must prepare for and adjust to.

TRADE AND ECONOMICS

While the story on the security front seems to offer up a refreshing degree of continuity thus far, the same cannot be said for trade and economics. While Mr Trump is not an isolationist, he is an unapologetic protectionist and mercantilist. As if to drive home that very point, he made the withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) the first of his wave of executive orders. In so doing, he sent a clear signal that he is not interested in multilateral trade agreements, which he feels disadvantage the US, and will pursue only bilateral agreements where, presumably, he will have more negotiation leverage.

Much has been made about the death knell that Mr Trump sounded for the TPP. Two points should nevertheless be made in this regard. First, the TPP is not quite dead; not yet, anyway. Technically, the remaining 11 signatories can still salvage the TPP by amending the enactment rules so that US participation is no longer required for its implementation. Of course, while this may keep the TPP alive, the absence of the US will render it a less compelling trade agreement.

Second, the fate of American commitment to the TPP was already hanging in the balance anyway. Lest we forget, just about every presidential candidate opposed the TPP. This included Mrs Hillary Clinton, an architect of the agreement.

There remains legitimate concern that the US might indeed still be headed towards a trade war with China. While Mr Trump's national security team can still be defined by continuity, his trade team appears intent on disruption on the back of rather bizarre macroeconomic logic that will see debt balloon even further because of increased spending, increased borrowing and reduced taxes. Indeed, the "America First" agenda is staring a massive current account deficit in the face. Yet, the Trump team comprises individuals who have made a career of anti-China protectionism, and they are intent on taking the US down this road.

Because of this, relations with China will have to be managed carefully and strategically in terms of how the trade and security agendas can be reconciled in hopefully reassuring ways.

There is no doubt that the personality of the President and his unfamiliarity with the mores that govern the corridors of power in Washington have struck a discordant chord, even within his own party. Indeed, the polarised atmosphere in American politics means that some people are cognitively predisposed to seeing and thinking the worst of him.

Yet, for us in Asia, such frustrations that bedevil the American electorate should not be allowed to dominate discussion on the possible shape of the Trump administration's foreign policy in our region.

On that score, Mr Trump's bluster aside, the early signs do point to some degree of relief, especially on the security issues; but there is serious cause for concern when it comes to the trade and economics side of the ledger.

- The writer is dean and professor of comparative and international politics at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University.