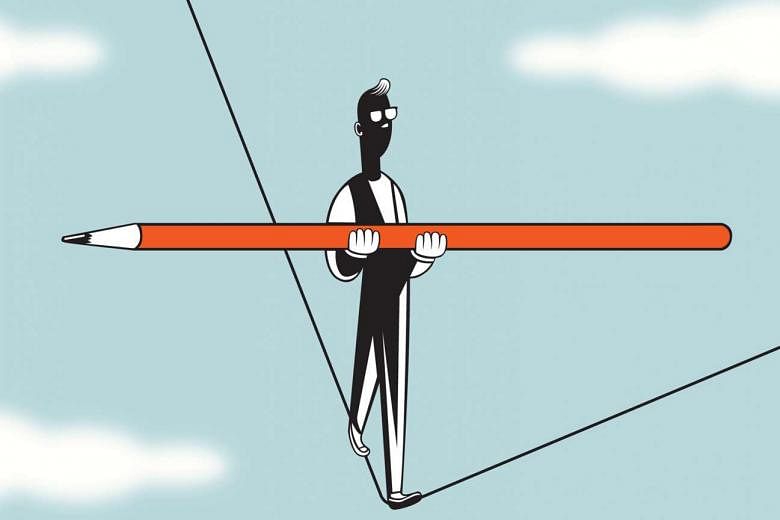

No one in their right mind would ride a bicycle over the Alps. Yet, according to Canadian short story writer Mavis Gallant, this is what the writer of fiction does. Or, to use Margaret Atwood's analogy, writing fiction is like walking a tightrope - "look down once and you've had it".

Think of it this way - if the writer's modest vehicle of conveyance is a fabric of words, then the Alps so skilfully crossed are an exploration of the vagaries of the human soul. The immensity of the task and the inadequacy of the tools at hand are daunting for any writer.

What impels an ostensibly sane person to spend a lifetime examining the lives of people who do not exist, and to consider such an occupation perfectly rational? Writers are surrounded by their own lives, by where they were born and where they have travelled to both geographically and emotionally. We have to survive our own history if we are to write at all. The writer writes not to escape life but to pin it down, pulling it up for examination in the light through the mysterious waters of memory.

It is not my fault that I write; it is a force I did not ask for and a destiny I accept. With that acceptance, I believe, comes moral responsibility, to speak truly, to bear witness to the minutiae with which we all struggle in our lives, of grief and loss, love and jealousy, death and joy. Throughout time, this is what writers have always done - illuminate thought, archive emotion, record the growth and decline and the peccadilloes of society after society throughout civilised time, speaking always against oppression where it is found.

Creative writers are happily rooted in the tangible. The way raindrops hit a leaf is more exciting to a writer than Einstein's Theory of Relativity. The sun behind clouds and the warmth of tears upon a cheek, the way a mother looks at her child; the perception of these sensations is what makes a writer. Often a writer does not write about what is seen directly, but about what is observed out of the corner of an eye. Walking along a road at night, a writer might see a lit window that reveals a family at dinner; a picture on a wall, an expression of sadness on a face, the flourish of an angry hand. Through these glimpsed fragments, the writer weaves a story.

Characters can emerge wraith-like from the mists, or present themselves more definitely. I once found a character called Arthur one morning, waiting for me at my desk and demanding a place in my novel, and I could not deny him. Strangely, if characters are based upon real people, the result is often not convincing. A character taken directly from real life is hemmed in by the author's own emotions and cannot expand and grow emotions of his own, and so is less truthful than one drawn from the writer's imagination. Once a fact crosses from reality into the author's imagination, it becomes the possession of the writer and a change in its basic components takes place in some mysterious way.

Writers experience many lives in one. From their desk, they can travel the world, or go backwards and forwards in time. They can set themselves down in ancient China or project themselves into the future and describe those destinations in exact detail. A writer can wind the clock of a story backwards and forwards. Time can stand still for the length of a book or a lifetime can be lived within a few pages, or, tent-like, it can cover generations. A writer can become a king or a pauper, a devil or a saint. One famous Japanese novel by Soseki Natsume is called I Am A Cat and is written from the viewpoint of the family cat.

E. L. Doctorow, in his novel City of God (2000), says, "Migod, there is no one more dangerous than the storyteller."

And the Danish writer Isak Dinesen, best known for her 1937 memoir Out Of Africa, in her story, A Consolatory Tale (1957), describes the transformation of an otherwise insignificant man as soon as he assumes the role of storyteller.

" 'Yes, I can tell you a story,' the man said. During this time, although he kept so quiet, he was changed; the prim bailiff faded away and in his place sat a deep and dangerous little figure - consolidated, alert, ruthless - the storyteller of all the ages."

All writers understand this inexplicable split within themselves; the two people lumped together under the one name of writer. There is the person who walks the dog, goes to the market, collects the children from school and so on. And there is the other, more shadowy, equivocal person who shares the same body and who, when no one is looking, takes it over and uses it to commit the act of writing, living a thousand lives in many unknown skins.

I implicitly trust that "other" person within myself, no more discernible to my mind or on the page than the light of a sunbeam. However many times I set off on a novel's uncharted voyage, I know I will be guided as we journey together. When, at the end of a book, I am at last washed up upon a distant terrain, I am always surprised at how surely I have been guided, how safely I have landed.

The ways in which a novel evolves are a mystery to me still. Just as academic work is organised around inflexible intellectual logic, the novelist's work is also highly organised in its own organic way, but around a structure of imaginative and emotional logic. At the inner crossroads of the rational and irrational, the novel produces a logic that is entirely its own, and that must be embraced. This is the tightrope all writers of fiction need to walk.

All this, and yet the role of writer is often dismissed as dilettantism, not a "proper" job. "Done any more writing lately?" "Nice hobby." Writers get used to such comments, but grow incensed at this demeaning dismissal of their life's work.

A hobby is an amateur pastime, a leisure activity. This is not what serious writers do. The writing job may be bizarrely different from that of the banker, lawyer or the civil servant, but it is no less "proper" in its demand for discipline, commitment or skill. Most writers must also hold down a full-time job, no matter how humble, to pay the rent and feed their families, before they can turn to their real work.

Writer Susan Sontag's corresponding anger at the ignorance of public perception is worth quoting. "I make coffee, and I go to work. And I work until I drop... A day in the life of a writer - this writer - is getting up and doing it all day long, and all evening long, and sometimes till 3 or 4 in the morning."

"Writing is a way of living," the famous French novelist Gustave Flaubert declared in one of his marvellous letters to his many friends. Indeed, writers across time and across the world know the truth of those words.

•Dr Meira Chand has written eight novels, including A Different Sky, set in Singapore. She wrote the story for award-winning The LKY Musical. She is involved in programmes to nurture and promote young writers, and is a board member of the National Arts Council.