When news of the settlement of the Keppel bribery scandal in Brazil first broke just before Christmas, I received a few messages, including from some well-known Singaporeans, expressing indignation that the United States government had been involved in the investigations of Keppel Offshore and Marine (O&M), the ship-and rig-building arm of the parent Keppel Corp.

One message read: "What business is it of the US Justice Department to prosecute corruption in other countries? Should they not focus on American corruption?"

Another, which was also copied to the editor of The Straits Times, suggested, in a similar vein: "What Keppel O&M and the Brazilians did is none of America's business. The Yanks have arrogated to themselves extra territorial jurisdictional powers and are plain extortionists. Who appointed them the world's policeman?"

I heard similar sentiments expressed in conversations that I had, including (to my surprise) with people who worked for companies with global operations. Implicit in such views is that dealing with bribery should be a purely national affair.

That's how it largely used to be, up to the 1990s. While the United States Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA), passed in 1977, prohibited the bribery of foreign officials, European laws were less strict. In many countries of the European Union, including France and Germany, a bribe given to a foreign official was even allowed to be a tax-deductible expense.

The United States objected, pointing out that such uneven standards put US companies at a competitive disadvantage vis-a-vis their European counterparts.

Pressured relentlessly by successive US administrations, France and Germany finally decided to act. But they didn't want to be the only ones to be penalising foreign bribery, which would handicap their companies compared with those of other countries.

LAWS WITH GLOBAL REACH

So they lobbied, successfully, for all of the members of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) to join an anti-bribery convention, which was formed in 1997. Since then, all OECD countries have applied the same criminal standards to the bribing of foreign public officials.

Over the years, some non-OECD countries also joined in, including Argentina, Brazil, Bulgaria, Colombia, Costa Rica, Russia and South Africa - although not yet Singapore. So far, 43 countries have joined the convention. China, Malaysia, Indonesia and Peru have participated as observers.

Anti-corruption enforcement officials from all these countries find the convention invaluable. They meet at least four times a year, exchange notes and update their practices. They also collaborate. So as business became more global, anti-bribery enforcement became increasingly multi-country efforts.

The global war against bribery got another boost with the United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC), which came into force in December 2005. UNCAC, which had 140 signatories, including Singapore, obliges all parties to help one another in every aspect of the fight against corruption, including prevention, investigation, and prosecution of offenders, extending to even extradition. So now, many of the provisions of the FCPA have effectively become multilateralised.

In 2014, the FCPA's enforcement actions against non-US companies exceeded its actions against US companies for the first time. The trend has accelerated. As of now, eight of the 10 top FCPA enforcement actions of all time (Keppel is seventh on the list) related to non-US companies.

In the Brazilian bribery scandal dubbed Operation Car Wash in which Keppel was implicated, the biggest cases were all multi-jurisdictional investigations with coordinated settlements involving several countries. Evidence against Dutch company SBM Offshore was provided by enforcement agencies from Brazil, the Netherlands, Switzerland and the United States. British engineering group Rolls Royce, which admitted to paying bribes not only in Brazil but also in several countries between 2000 and 2013, was investigated through the joint efforts of officials from Brazil, the United Kingdom, the US, Austria, Germany, the Netherlands, Singapore and Turkey.

In the case of Brazilian company Odebrecht, evidence came from Brazil, Switzerland and the United States. The investigations into Keppel involved agencies from Brazil, the US and Singapore.

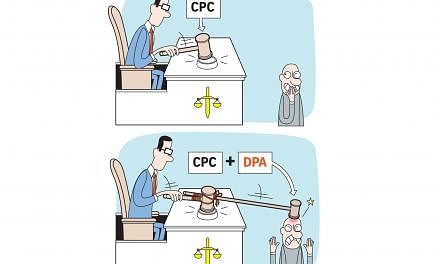

So, companies operating globally, as increasing numbers of Singapore companies are doing, now need to be concerned not only about the compliance requirements of the countries in which they are operating, but also those of the United States and a host of other countries - which significantly increases the risk of getting caught.

Singapore companies operating abroad must also be mindful of Singapore law - even if they do no business here. Singapore's Prevention of Corruption Act has extraterritorial powers to deal with corrupt acts conducted outside Singapore as though they were committed in Singapore.

BROADER RISKS OF EXPOSURE

Nor are national enforcement agencies the only risk that companies face. In another high-profile case of 2017, Monaco-based consulting firm Unaoil was revealed to have been running, for more than a decade, an industrial-scale bribery operation across 16 countries spanning the Middle East, central Asia and Africa to obtain contracts for its clients in the oil industry.

Much of the most incriminating evidence that uncovered this audacious scheme came from 10 years of confidential e-mails between top executives of Unaoil and its multinational clients that were leaked by an anonymous source to Australian newspaper The Age and US media portal The Huffington Post.

In 2016, we learnt of the so-called Panama Papers, which consisted of more than 11 million documents from a Panamanian law firm leaked without any demand for compensation by an anonymous source to German newspaper Suddeutsche Zeitung. The papers, which were shared with some 400 journalists around the world and posted on the website of the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) (https://www.icij.org), exposed a cast of characters - many of them highly placed - who used offshore companies to facilitate not only bribery but also illegal arms deals, financial fraud and drug trafficking.

The Panama Papers have triggered investigations in 80 countries.

Then in November last year came the Paradise Papers - a trove of more than 13 million records from offshore services firms and government-maintained corporate registries going back to 1950, detailing the offshore dealings of prominent companies and individuals. These documents were also leaked anonymously to the Suddeutsche Zeitung and again shared with the ICIJ.

There are also several non-governmental organisations which monitor bribery around the world and share their findings. For example, many of the impressive resources of New York-based anti-bribery business organisation Trace International, which also provides compliance support, are available free to anyone. (http://traceinternational.org)

Companies with global operations must therefore be mindful that they are now operating in a world of high transparency and vigilance. In countries where bribery is commonplace, it may be especially tempting to go with the flow and conform to local norms or else risk losing business.

But companies must balance that risk against the rising risks of getting caught - which can come not only from the national enforcement agencies of multiple countries, but also from other sources - including anonymous individuals who want only to expose wrongdoing and expect nothing in return.