It is ironic that just as the United States and Europe are undergoing wrenching political turmoil, the world economy is actually recovering. The International Monetary Fund reflects a consensus view that almost a decade after the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression, a global economic recovery is clearly under way. Even the US, probably despite rather than because of President Donald Trump, is approaching full employment.

But the greatest beneficiary of this sustainable recovery will actually be Asia, as it will enjoy two engines of growth - consumer demand in its traditional Western markets, but now also rapidly accelerating demand from its own middle classes.

Thirty years ago, 90 per cent of the Asian population came from what the World Bank defined as low-income countries. Today, 95 per cent of Asians live in middle-income economies. A single generation has lifted hundreds of millions of people from poverty to middle class.

What does all this mean for investors in Asian companies?

First, the Asian story is a long-unfolding one, with periodic downturns and bursting bubbles, so we have to understand the long-term implication of what is happening, and be resilient enough to accept periodic cycles.

Second, companies which have a global orientation but a particularly strong Asian narrative will benefit doubly from current economic improvements across the globe.

Third, companies which focus on the growing wallets of Asian consumers will do particularly well.

The Asian narrative is usually bookended by its two largest economies, India and China. Often overlooked is the middle region, the 600 million people of South-east Asia, or Asean.

Economic growth in the Asean 5 - Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam - will exceed 5 per cent for the next decade, compared with 3 per cent in North Asia. South-east Asia's entire workforce is still growing, while that of North Asia is already contracting.

Because of its relatively fragmented markets, its linguistic, cultural and religious diversity, and geographic dispersion across both landlocked and archipelagic nations, many investors have tended to bypass investment opportunities in Asean companies.

What they may not realise is that precisely for these reasons, there is more likely to be an overvaluation of large Indian and Chinese corporates, and underestimation of the oligarchic and opaque governance in these economies.

On the other hand, Asean medium-sized corporates that have become successful regionally have done so with little support from their governments. Asean medium-caps are therefore very competitive, lean and able to manoeuvre deftly in the Asian landscape.

With economic integration across the South-east Asian economies rapidly growing, not due to (rather ineffective) Asean intergovernmental cooperation but because of their own business communities, the potential for Asean corporate growth is more underestimated than in its two larger neighbours.

But while the increasing wealth and size of the Asean middle class are encouraging, one area of concern is what economists call the middle-income trap.

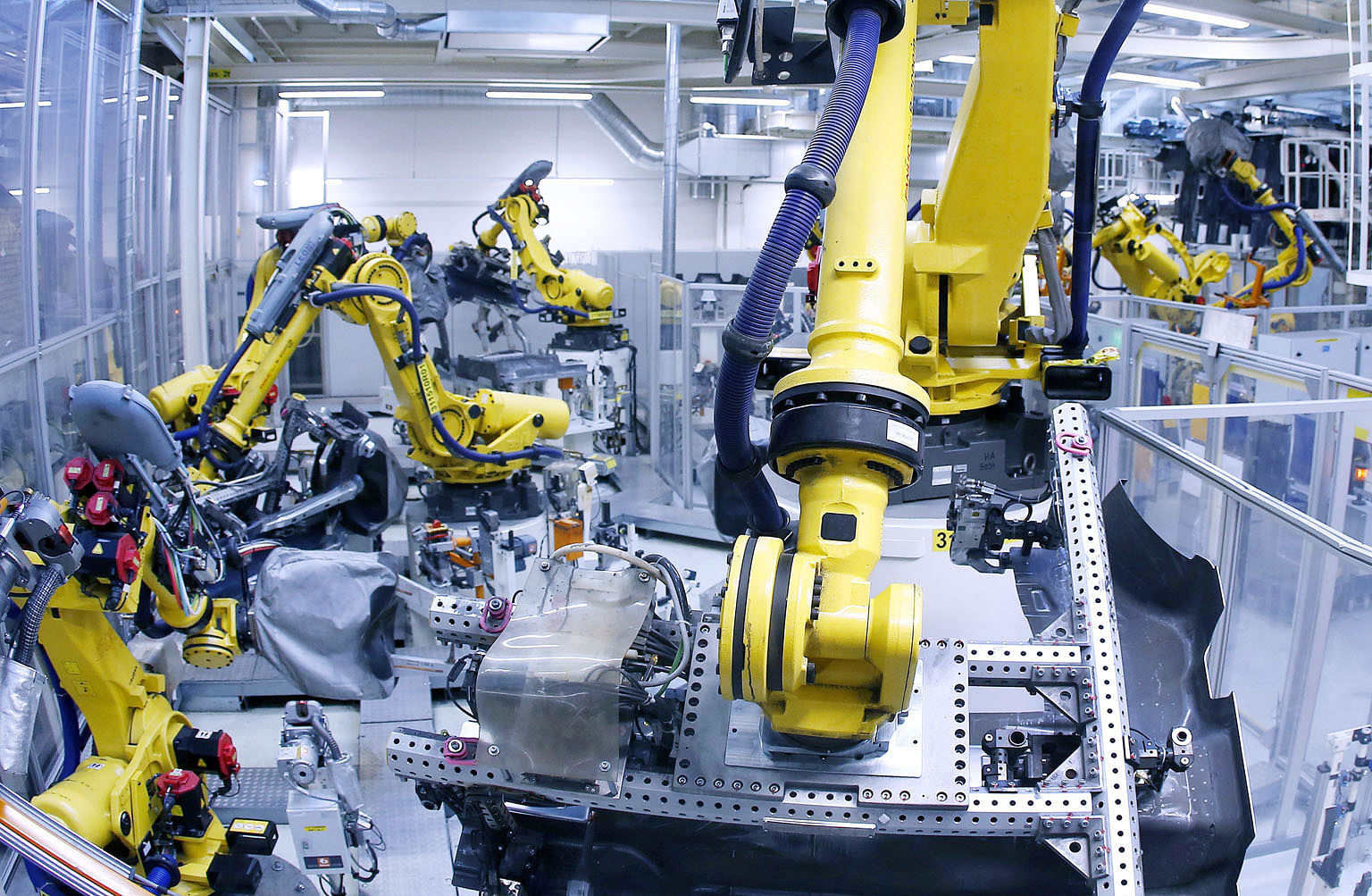

The very successful model of export-led, labour-intensive and natural resource-dependent growth, which propelled South-east Asian from poverty to wealth in a few decades, will be threatened by what the World Economic Forum calls Revolution 4.0, or what others call the Fourth Industrial Revolution. This disruptive change will be marked by revolutions in genetic engineering, robotics and artificial intelligence, nanotechnology and biotechnology. Computers and the Internet age will be ancient history.

One example of this disruptive change: The International Labour Organisation predicts that robots will replace 85 per cent of the workers in the Vietnamese textile and garment industry over the next two decades. That may seem like a long time, but possibly not nearly long enough for an entire industry and country to transform itself and its economic models.

Asean business leaders are well aware of possibly falling into what has been dubbed "premature deindustrialisation", where economies just on the verge of large-scale industrialisation - Indonesia and Vietnam, for example - are overtaken by post-industrial robotics which are so inexpensive and productive that they can even replace a workforce which is still cheap by developed-world standards, but already expensive and inefficient by robot standards.

To overcome this, Asean economies need to innovate with even newer ways of producing and marketing, as well as creating new "things" for consumers.

But it is not happening fast enough. At a recent Singapore seminar, I asked an eminent Thai business leader what he considered the single biggest challenge for his company, a listed company in Thailand and the largest producer of a particular industrial product in Asia. Without skipping a beat, he said: "Innovation. We do not spend enough resources on innovation, and nobody else does either, compared to the West."

As for Singapore, we are an economy in transition, somewhat of a hybrid between a quite competitive, productive and sophisticated export platform and a somewhat low-skilled and low-cost domestic economy. We are also a hybrid - being one of the most open and free-market economies in the world, but led by government-dominated corporates and guided by carefully planned and executed road maps for strategic industrial clusters.

And having attained developed economy and high labour cost status many years ago, Singapore's economic future depends on relentless innovation at the corporate level and reinvention at the national level.

The Committee for the Future Economy, the latest of many public-private committees formed since independence 50 years ago to identify and then nurture strategic new sectors, will undoubtedly produce winners in due course.

After several centuries of civilisational decline, Asia is ascendant. It will be a long cycle, punctuated by periodic bursting asset bubbles and economic cycles, but the trend is sustainable and palpable. Long overlooked by its larger and more homogeneous neighbours, South-east Asia is uniquely placed to benefit disproportionately from these trends. But the dangers are equally apparent as disruptive change can unexpectedly stall its rise. South-east Asian thought leaders must rise to both the opportunities as well as the challenges.

- The writer is the executive chairman of Banyan Tree Holdings, a Singapore-based leisure business group.

- This article was adapted from a keynote speech to the Brave New Asia Investor Forum organised by the Bank of Singapore.