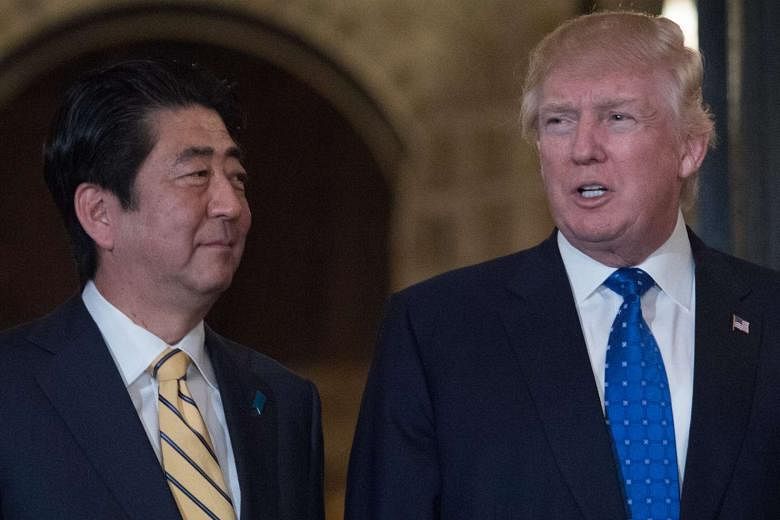

Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe's visit to the United States, bearing tribute in the form of billions of dollars of pledged direct investments that will create thousands of jobs, raises an intriguing question.

While China and the US were allied against Japan during World War II, will the US and Japan ally against China in World War III?

This is not a forecast but it is a not implausible scenario.

True, Mr Donald Trump's belated confirmation to Chinese President Xi Jinping that Washington will adhere to the "one China" policy - and not, as was feared, kindle the fires of recognising Taiwan as a separate and independent state - postpones and, at least for now, diminishes the plausibility of the scenario.

But Japan's starkly Janus-faced political attitude towards its former enemies can still be illustrated by the following observations.

While Mr Abe visited Pearl Harbour in late December, a visit to Nanjing or other Asian sites where Japanese troops committed atrocities did not follow.

Instead, Defence Minister Tomomi Inada made a very public visit to the Yasukuni Shrine, which commemorates a number of prominent war criminals guilty of atrocities against the Chinese and other victims of Japan's militarism.

During World War II, Korea was a Japanese colony and forced to supply young women as sex slaves to Japanese soldiers, in a hideous practice known in Japanese as ianfu (comfort women).

Following the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the USSR joined the China-US alliance against Japan, and Korea was liberated from Japanese colonial rule on Aug 15, 1945.

Divided between North and South, war broke out in 1950 and concluded in a stalemate - not a peace treaty - in 1953, resulting in two national entities: the Democratic People's Republic of Korea in the North and the Republic of Korea in the South.

North Korea is officially an ally of China, and South Korea an ally of the US - as Japan has been since 1952.

North Korea is the world's last Stalinist redoubt. Unlike its nominally communistbrethren, China and Vietnam, North Korea has not undertaken market reforms, and is not integrated into the global market economy. It is also an emerging nuclear power and one of the four world nuclear powers not to have signed the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, besides Israel, Pakistan and India.

Despite the very tense nature of the relationship between South Korea and Japan, the two countries are both allies of the US, so Washington is trying to bolster the bilateral relationship as a means to contain not only the North, but also China.

Part of the effort has resulted in imposing on South Korea the US-made missile shield known as the Terminal High Altitude Area Defence (Thaad) platform.

China remains both Japan's and South Korea's most important trading partner.

The geopoliticisation of business in the Asia-Pacific is illustrated by the fact that, in putting pressure on South Korea to oppose the deployment of Thaad, Beijing has, for example, forced Hyundai Motors to postpone the launch of its Sonata plug-in hybrid in China and the Lotte Group to renounce its US$2.6 billion (S$3.7 billion) Chinese theme park.

Beijing has also "blocked imports of high-tech bidets and some cosmetics, cancelled music concerts by South Koreans and restricted Chinese flights and tourism to Korea", according to a report in the Financial Times .

In contrast to the post-World War II settlements in Western Europe, the post-war situation in the Asia-Pacific is extremely messy.

ASIA-PACIFIC WOES

This arises from a combination of historical legacies of deep enmity and carnage, ideological differences and territorial disputes.

For instance, Japan has territorial disputes with its former enemies China and Russia, and with its former colony Korea.

While paying tribute to its former enemy, the US, as a means of bolstering the alliance to defend it from China, Tokyo has also been trying to cosy up to Moscow.

Mr Abe has been courting Russian President Vladimir Putin, including an invitation last December to share a hot spring bath - the so-called "Onsen Summit" - in his home town of Yamaguchi in western Japan.

Arguably, the hottest fault line in the Asia-Pacific is in the South China Sea, where a naval confrontation between China and the US is another scenario that is not implausible.

Mr Trump's recently appointed Secretary of State Rex Tillerson's sabre-rattling - by threatening a possible US blockade of China's access to the islands in dispute - significantly raised the Sino-American geopolitical temperature.

With the current business environment rather murky, to put it mildly, there would seem to be one possible bright spot, as I argued in a Straits Times article last September ("New Silk Road - a ray of sunlight on a gloomy horizon?"; Sept 16).

The China-initiated New Silk Road and Maritime Route has the potential of not only rebooting and reshaping the world economy, but also providing a means for China's "peaceful rise".

However, with both the US and Japan showing resistance to the project, the relationship between Russia and China remains ambiguous at best.

While China and Russia share a border of more than 4,000km, for as long as they have been neighbours, they have rarely - if ever - been friends.

Central Asia, through which the Silk Road would pass en route from Xi'an to Rotterdam, has since czarist days been part of Moscow's sphere of influence, and its nations were integrated into the former USSR.

Now, Russia badly needs China economically, but it remains to be seen whether that is sufficient to prevent future conflict.

India, with which China also shares a more than 4,000km border, looks upon the Silk Road project with suspicion, especially as one of its current key components is the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, which provides China with access to the Indian Ocean via the Pakistani port of Gwadar.

So what to make of all this?

Twenty-six years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, we are very far from the prospects of a "new world order", "the end of history" or the "peace dividend".

Though the geopolitical panorama is very cloudy - and, hence, difficult to decipher - it would seem that we are in a 21st-century variant of the "age of empire", in which the dominant actors are China, Russia and the US.

China, after more than a century of humiliation as the victim of imperialism, is the newly rising empire.

Russia is a declining and asymmetric empire, with its geopolitical ambitions and military clout masking its economic weakness.

Does that make the US an empire under Mr Trump?

It's difficult at this stage to say.

Showing both isolationist and interventionist propensities, from an Asia-Pacific perspective, America seems to be materialising into the proverbial bull in the china shop.

Other countries in the Asia-Pacific, as well as in South, Central and West Asia, will be caught in the rivalry between the three dominant global empires - the "Great Game" of the 21st century.

What are the implications for business?

At a time when the erstwhile global multilateral rules-based trading system has been derelict for some time and will clearly be made even more defunct under Mr Trump, business will be increasingly subjected to political pressures - as illustrated above in the case of Beijing and corporate Korea clashing over Thaad.

Imperialist geopolitics are back… and with a vengeance!

- The writer is emeritus professor of international political economy at IMD business school, with campuses in Lausanne and Singapore, and visiting professor at Hong Kong University.