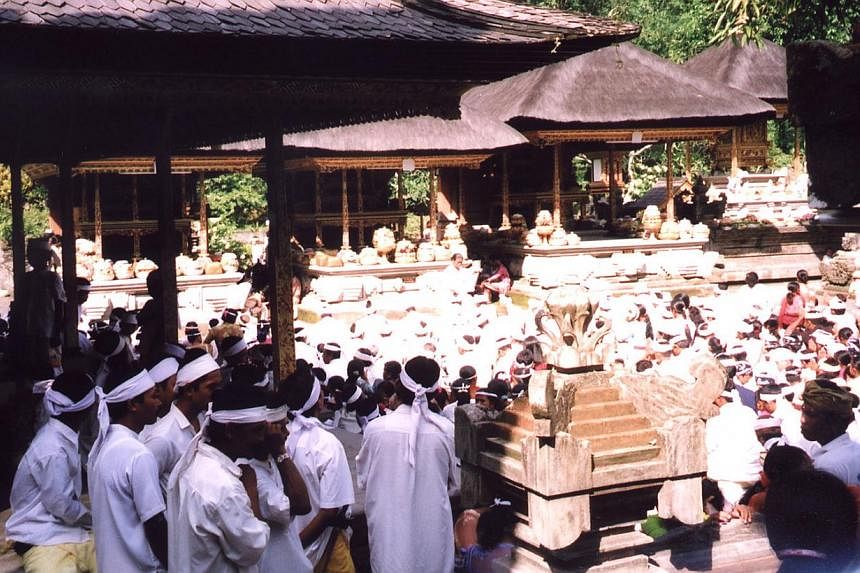

YEARS ago, while among a throng of foreign tourists milling around a Balinese temple, I watched a sari-clad Indian standing before me.

She wanted to pray in the temple's inner sanctum, although it apparently was off-limits to non-locals. A guard blocked her way. "I am Hindu," she said gently. "You not Hindu," he replied without rancour. "You Indian." Although Hinduism had come from India, to him Hinduism meant Balinese Hinduism.

The guard registered an essential point about the identity of South-east Asia: It is distinctive because of its intensely local character.

True, South-east Asia lies south of China and east of India. Visualised historically as the "Nanyang" in the Chinese mind and as "Suvarnabhumi" in the Indian worldview, it formed the crossroads of Sinic and Indic civilisations. But the crossroads developed its own character, an inclusive one that produced syncretistic and eclectic national cultures from Thailand and Indonesia to Singapore and Vietnam.

The strongly localised culture of South-east Asia's 600 million people preserves a cherished religious diversity. According to the Association of Religion Data Archives, Islam accounts for about 37 per cent of the population, Buddhism 27 per cent, and Christianity 22 per cent. Buddhism dominates the continental part of the region and Islam the maritime.

This diversity, which exists in spite of terrorism and the seepage of religion into politics, makes it unlikely (though not impossible) that theocratic states in the mould of Iran will emerge in the region. The absence of hegemonic religions makes South-east Asia important to the multi-religious population of secular Singapore.

Then there is geography.

Every time the haze envelopes the region, Singaporeans realise the power of geography, in the form of the forest fires that burn in Indonesia next door. But geography can be protective as well, as when Indonesia and Malaysia, like two interlocking arms, shielded Singapore from the Indian Ocean tsunami of 2004. It devastated Aceh, and hit Penang and Langkawi, but left the city-state intact.

Geography contours the security of regions.

The intrusion of colonialism in the 16th century disrupted South-east Asia's position as a node in intra-Asian trade and cultural links. The warring nations of expansionist Europe redrew the region in their imperial image, right down to World War II, when the Allies set up the South East Asia Command in 1943. The Cold War divided the region between the contending global ideologies of capitalism and communism.

But the foundations of regional security were laid during the Cold War itself, when the Association of South-east Asian Nations (Asean) was founded in 1967. It brought together five non-communist states - Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore and Thailand - and Brunei when it became independent in 1984.

After the end of the Cold War in 1989, Asean became a truly South-east Asian organisation by expanding to include the formerly communist states of Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam, along with socialist Myanmar. Timor Leste and Papua New Guinea are currently seeking accession.

The association also developed its external "wings" in the form of the Asean Regional Forum (ARF) and the East Asia Summit. These mechanisms offer the great powers a platform on which to engage and court the 10 nations of Asean.

A dramatic illustration of the engagement was the ARF meeting in Hanoi in 2010. Former United States Secretary of State Hillary Clinton underlined the importance of South-east Asia when she spoke of America's "national interest in freedom of navigation, open access to Asia's maritime commons and respect for international law in the South China Sea".

The use of "national interest" was a pointed rejoinder to China, which had elevated the South China Sea to the level of a "core interest", on par with Tibet and Taiwan, which were integral to Chinese sovereignty. America's top diplomat was telling Asean that Washington would not let an assertive Beijing set the terms of international behaviour unilaterally.

South-east Asia is not without access to countervailing external power even in an Asia marked by the competing ascendancies of China and India. The naval interests of India, gravitating eastwards, and China's westward movement intersect directly in this region, which often has functioned as a buffer zone.

Maritime South-east Asia remains crucial to America's policy of forward deployment, which enables it to fight wars of choice far from its shores. US naval access to the region is an integral part of its pivot to the Indo-Pacific. This newly defined strategic space stretches from India to the western shores of America, at a time of heightened strategic confrontation as China asserts itself in the East China and South China seas.

But more than guns, it will be butter that will create a coherent Asean.

Asean's policies of integration could churn up richer butter. According to an Economist Corporate Network report last year sponsored by the global law firm Baker & McKenzie, multinationals operating in the region are finding those policies meaningful because they bring together 10 national markets to form a large regional market in spite of nationalist and protectionist sentiments.

Indeed, the report adds, Asean is already attracting seven times more foreign direct investment than India, and almost the same amount as China, on a per capita basis.

If this momentum continues, the Asean Economic Community will not be a pipe dream, even if all its goals are not achieved by next year.

South-east Asia will arrive truly when a child in Singapore or Jakarta thinks that she is eating Asean peanuts or ice-cream.

And the next sari-clad woman - presuming she is an Indian from, say, Singapore or Malaysia - might find her way into a Balinese temple by declaring that she is an Asean Hindu.

The writer, a former Straits Times journalist, is an associate fellow at the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.