Much like the world beyond its borders, Thailand is going through a political malaise that naturally accompanies the transition at the end of a 70-year-long era.

For the world, this period is characterised by the unravelling of the global liberal order that was constructed and led by the United States in the aftermath of World War II. For Thailand, the period that has run its course coincided with King Bhumibol Adulyadej's remarkable reign from June 1946 to his passing on Oct 13 last year.

As his longevity shaped the country's socio-political setting and economic development over 70 years, the late monarch's passing necessarily entails a reset of Thai society and politics as the country ushers in a new reign. The constituent actors of the new reign under King Maha Vajiralongkorn, in turn, have to come to terms and agree on a new modus vivendi as to how Thailand should function and operate. This unfolding process of new politics under a new reign will take time and requires compromise and accommodation to be peaceful and workable.

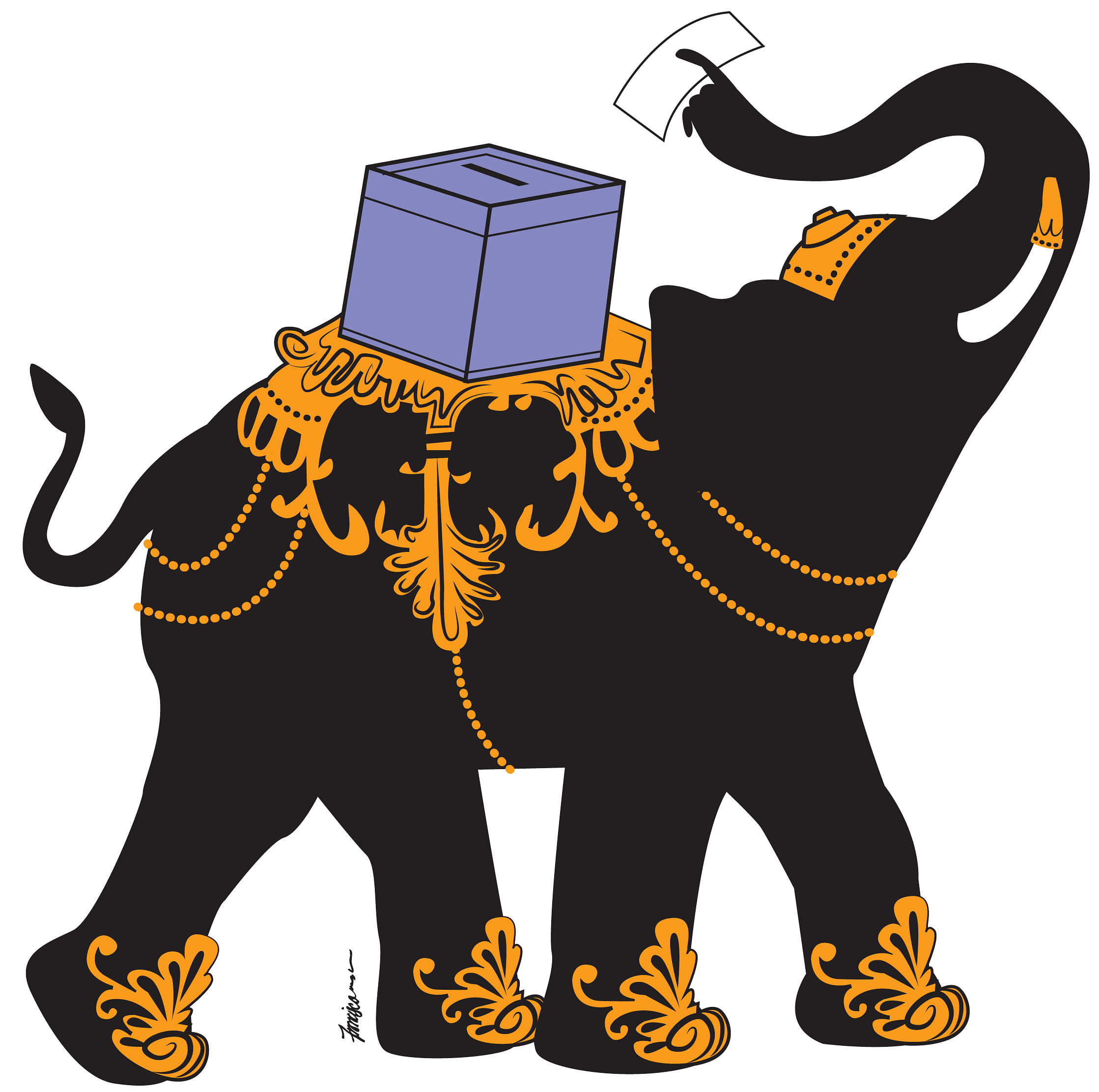

The benchmark for Thailand's return to a semblance of normalcy after a topsy-turvy decade of elections and coups is to have a government that is popularly elected and publicly accountable, not the current military regime under the National Council of Peace and Order. To be sure, the junta has served its purpose of being the midwife of the royal transition, and the Thai public has cut it slack along the way, for example, by passing the military-inspired constitutional referendum last August by a convincing margin with a large turnout. But now that a new reign is settling in, the junta's expiry date appears in sight.

An election is unlikely until there is a proper royal cremation that befits the glorious era of the late monarch. The earliest date would be roughly one year after his passing on Oct 13 but this final goodbye by the Thai people will probably take place only after the rainy season in late November or December at the earliest, putting the polls in early to mid-next year. The cremation of King Bhumibol may be viewed in conjunction with the coronation of King Vajiralongkorn. The circumstances may be more conducive to have the coronation under an elected government with a measure of political reconciliation as myriad heads of state and royalties from around the world will be invited. A junta-backed military government would not be the right kind of host for such a prestigious event.

This sequence assumes that the draft Constitution, which is being amended in parts dealing directly with the monarch's prerogatives concerning the regency, will receive royal endorsement and be implemented on time by the middle of the year. If it is rejected along the way, a new Charter will have to be written, thereby further delaying the election.

Thailand's political future is uncertain because it is unclear whether the new monarch would be willing to go along with a military-dominated Constitution written by a small military-appointed committee with the aim of having the military supervise Thai electoral politics for the long term. The Constitution states that 33 per cent of the seats in the legislature be reserved for military personnel and their proxies. This pro-military charter was a done deal before King Vajiralongkorn's ascension to the throne and, therefore, the new monarch may not want to be bound by a document that covers royal roles and duties without royal input.

King Bhumibol's relationship with the military was symbiotic, and the two institutions were like two sides of the same coin in ruling Thailand throughout the Cold War. The new King and a new reign will likely spell changes to Thailand's political configurations and dynamics, a changing of the guard whereby some former handlers and advisers under King Bhumibol would be replaced by King Vajiralongkorn's preferences. Already, the newly appointed Privy Council under the new monarch is composed of newer figures, although the 96-year-old General Prem Tinsulanond remains its chairman. The new reign may also bring about a more level-playing field in Thai politics in the near term.

In view of Thailand's political divide between pro-establishment conservative royalists - broadly the "yellow" side - and the pro-electoral democracy "red shirts", many of whom but not all are supportive of ousted and exiled former prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra, the pattern in Thai politics has been that the pro-Thaksin red shirts would win election time and again (in 2005, 2007 and 2011), only to be overthrown by street protests that led to judicial interventions and military coups. In doing so, the "yellow" side mobilised and acted against corruption and abuse of power and cited morality and ethics as their motivation. The yellows were at once loyal to the throne and to the late monarch, which to them was one and the same.

The reds, on the other hand, insisted that they too were loyal to the monarch but some of them perhaps felt that their nemesis exploited the name of the monarchy against them. Now the tables may be turned under the new King. The yellows are certainly loyal to the monarchy and supportive of the new monarch but the complete symbiosis between the two may no longer hold as much sway as in the past. They still cling to the institution but perhaps are less certain about the individual.

Concurrently, the reds may still be sceptical of the monarchy but they perceive the new monarch as never having been used by, and never having stood with, the other side against them. So if the next election goes to yet another pro-Thaksin party, with the Democrat Party at the losing end because it has not been revamped after repeated poll losses, the "yellow" side may not be able to carry out anti-government protests in the name of the King in much the same way as in the past. To this extent, Thai electoral politics may be a fairer game. Accordingly, it is imperative for those who oppose Thaksin's corruption and abuse of power to win by beating him at his own game, that is, by winning the election. Otherwise the Thaksin side may win and be able to stay longer in office - unlike in the past.

All things being equal, Thailand's election would take place around the second quarter of next year, followed by the coronation thereafter. Delaying the election may be tantamount to delaying the coronation. Yet no poll can be expected until a fit and proper cremation transpires. The longer polls are put off, the more electoral forces, in particular, the main Pheu Thai and Democrat parties and their party machines, will agitate. In case of unexpected poll delays, one caveat would be the civilianisation of the military government, with a civilian leader at the helm, which may engender sufficient international legitimacy and credibility to move ahead with the coronation. How Thailand's popular rule will be shaped and formed under the new reign - and vice versa - will determine Thailand's way ahead.

•The writer teaches international relations and directs the Institute of Security and International Studies at Chulalongkorn University in Bangkok.